Water

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Earthworks Workshop

Happy March! Finch Frolic Garden is officially open, and the trees are bursting into leaf and bloom. Birds are twitterpating and the ten inches of rain we’ve received since October are slowly working through the soil thanks to our earthworks.

Here’s an opportunity to learn just how to create accurate swales and hugelkultur so that they work. Saturday March 11th from 1 -4 we have the privilege of having Alden Hough from Sky Mountain Permaculture hold our first monthly workshop here in the garden. Alden has

years of experience with building earthworks on all scales, from guiding excavators across hillsides to hand-dug. Alden will describe how to build swales and hugelkultur beds, show off equipment, and then its hands-on in the garden. You’ll learn how to use a laser level and a bunyip, and get the feel of how to build on contour. Bring your gloves and be prepared to have some fun creating earthworks, so that you can do it properly on your own property.

years of experience with building earthworks on all scales, from guiding excavators across hillsides to hand-dug. Alden will describe how to build swales and hugelkultur beds, show off equipment, and then its hands-on in the garden. You’ll learn how to use a laser level and a bunyip, and get the feel of how to build on contour. Bring your gloves and be prepared to have some fun creating earthworks, so that you can do it properly on your own property.The workshop fee is $20/person. Please RSVP to dianeckennedy@prodigy.net. Wear appropriate work clothes and sun protection. Complimentary vegetarian refreshments will be available. Attendees may stroll Finch Frolic Garden as well. Don’t wait!

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Swales and Basins in Action!

This week here in Fallbrook, CA, at Finch Frolic Garden we received almost three inches of rain in 18 hours. Our storm pattern is changing so that there are fewer rain events, but when it rains, it really rains.

This week here in Fallbrook, CA, at Finch Frolic Garden we received almost three inches of rain in 18 hours. Our storm pattern is changing so that there are fewer rain events, but when it rains, it really rains.  For many this was a flood. Precious rainwater is channeled away from properties and into the street. In permaculture gardens the water is harvested in the earth with simple earthworks such as swales (level-bottomed ditches) and rain catchment basins.

For many this was a flood. Precious rainwater is channeled away from properties and into the street. In permaculture gardens the water is harvested in the earth with simple earthworks such as swales (level-bottomed ditches) and rain catchment basins.Visitors have often expressed their desire to see the earthworks in action, so I took my camera out into the food forest.

That was when the rain gauge was at about two and three quarters, with more to come. (I wanted to photograph the garden after the storm had passed but my camera refused to turn on due to the indignity of having been wet. A couple of nights in a bag of rice did it wonders.)

That was when the rain gauge was at about two and three quarters, with more to come. (I wanted to photograph the garden after the storm had passed but my camera refused to turn on due to the indignity of having been wet. A couple of nights in a bag of rice did it wonders.)

Please excuse the unsteady camerawork, and my oilskin sleeve and dripping hand making cameo appearances in the film. I was using my hand to shield the lens from the rain.

- Animals, Bees, Compost, Gardening adventures, Irrigation and Watering, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Creating Rain with Canopy

Even if we don’t receive a lot of rain in drylands, we might have fog, sprinkles and other degrees of ambient moisture. This moisture can burn off with reflected heat from hard-packed earth, from gravel and hardscape, and from buildings. It is too irregular and thin to make the use of mist nets feasible. However, a much better way to collect that moisture and turn it into rain is the method nature uses: trees. The layers of a plant guild are designed to capture, soften and sink rainwater, so why not just let them do it? Many trees are dying due to heat, low water table, lack of rainfall and dry air. Replacing them with native and drought-tolerant trees is essential to help put the brakes on desertification.

Please take five minutes, follow this link and listen and have a walk with me into Finch Frolic Garden as this 5-year-old canopy collects moisture and turns it into rain:

Plant a tree!

- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Natives, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation For Drylands: Conclusion

One-inch PVC runs from the valve. This is the last of the series of posts on irrigation, and I’d like to briefly address the issues of water pressure and valves. As I’ve said in a past post, if you don’t know about these things then hire someone who is an irrigation specialist (not just someone who says he’s put together irrigation before… they are guessing!). That specialist will obtain for you the right sized valves, the right irrigation timer, and monitor the water pressure so that your sprinkler heads won’t blow off and pipes break.

The one-inch pipe is then reduced to 3/4″ pipe at the first T, close to the first sprayer. For pipe, don’t use small 1/2″ pipe for large jobs. Bigger – to a point- is better. Smaller pipe doesn’t mean higher pressure. It reduces the volume of water going to the sprinklers. The smaller pipe creates more pressure loss due to friction and turbulence as the water flows through it. We took the advice of our irrigation specialist and ran 1″ pipe from the valves to the first sprinkler, and reduced it to 3/4″ pipe, then reduced for the 1/2″ risers.

Further reducing 3/4″ to the 1/2″ sprinkler configuration. Most sprinkler systems need a water pressure of between 30 – 50 psi. Drip systems need less, around 20 psi. Too high or too low a water pressure will adversely affect your system. If you attach a water pressure gauge to a spigot you can see what your pressure is. If it is very high, you will want to check the indoor pressure as well because too high a pressure can mean pipe damage and leaks, and no one wants wet walls. You can use a pressure regulator on your line to reduce the water pressure for your irrigation.

How many sprinklers you can put on a valve depends upon several factors, but mainly the flow rate, or how much water is flowing through the pipes at one time. Sprinklers have an output rate so you can do the calculations on how many you can put on a line. Flow rates are measured either in gallons per hour or gallons per minute, with gpm the most common for householders. Drip systems are less concerned with flow rate. We ended up adding valves to our system because we had so many sprinklers.

How many sprinklers you can put on a valve depends upon several factors, but mainly the flow rate, or how much water is flowing through the pipes at one time. Sprinklers have an output rate so you can do the calculations on how many you can put on a line. Flow rates are measured either in gallons per hour or gallons per minute, with gpm the most common for householders. Drip systems are less concerned with flow rate. We ended up adding valves to our system because we had so many sprinklers.When installing your system, be sure to add a ball valve (rather than a cheap gate valve) close to your water source so that if you have to work on your system you can shut it off; otherwise you’ll have to shut off the main to your outside water. If you have a large system, installing ball valves along the line to isolate different areas will help down the road if you need to troubleshoot. Having hose bibs along the line are very nice, too.

There is a lot to learn about irrigation valves – using globe valves with an expensive back-flow preventer or using anti-siphon valves that must be above ground and above the closest sprinkler head. I’m not an expert, but there is expert advice on valves here.

Another thing to consider is your electrical line. If you have valves, you must run electrical line to them (at this writing, solar valves are not that dependable for the long run). Electrical line must also run from your irrigation clock to your electrical source at your house. Usually electrical line is buried. Please spend the little extra money and have the electrical pulled through conduit first, rather than direct burial! Having loose wires buried in your yard is a recipe for disaster. I know this. I asked for conduit with the original system, and the wire was directly buried before I could protest. Sure enough, two years in and a valve wouldn’t turn on. The problem was with the wire… but where? How to dig it all up without nicking any of the lines? Impossible. So until this project two of my valves had to be tied together and both stations running simultaneously, which really stunted the water pressure and was a real headache. This time the conduit is run above ground along with the PVC pipe, which will be covered with mulch, and also along the top of my chain-link fence up to my house. If there are any problems, the conduit comes apart every ten feet and wires can be checked or replaced. Pulling electrical wire through conduit is not for the fainthearted; I developed new muscles and callouses working on that, but it was worth it.

Skipping ahead, your irrigation project is finished and your landscape planted. Be sure to take the time to update your plan so that it is an ‘as-built’, reflecting any changes you’ve made. This is an invaluable document not only for your own use, but for any future owners of your property or workers who might need that information. Use a rough plan of your yard and identify each valve and the area the valve covers in different colors. If you want to draw in every sprinkler head, that is fine. On large projects that isn’t practical, so just use zones. Take a waterproof marker and write the valve numbers on the valves themselves, so that you won’t become confused in the field.

Be sure to run each valve during the daytime while you inspect the sprinklers for clogging or broken heads. A lot can go wrong during the night when most systems run, and you won’t know it until you get the water bill or your plants start to die.

You may want to put in the wire for additional valves that may be added in the future. Making double valve stub-outs and only using one is far easier than pulling new electrical if you find that you need to add a valve.

So don’t think that irrigation is a simple endeavor, and begin to glue miles of 1/2″ pipe together with 2 – 3′ risers that shoot water up embankments. This is a waste of money, plastic, water and plants. Put as much thought into your system as you put into the design of plants, and your system will give you little trouble in years to come.

Oh, and remember to shut your system off when it rains!

You can read Options, Part 1 of this series here, Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, and Designing Your System Part 3 here .

You can read Options, Part 1 of this series here, Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, and Designing Your System Part 3 here . - Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 3: Designing Your System

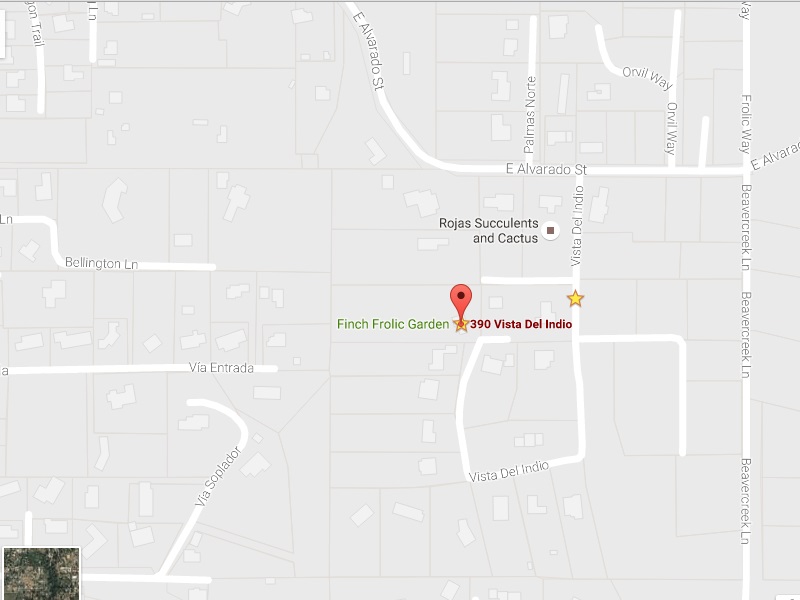

Google Maps view of property lines. Before you start buying pipe, make your design. If you are new to the property, evaluate the plants and features that exist and decide if you really want them or not. Use the ‘three positives’ rule in permaculture: everything in your yard should give you at least three positive things. For instance, you have a eucalyptus tree. It gives great shade, it is a great roost for larger birds which keep down your mice and rats, it drops lots of leaves for mulch, etc. On the ‘negative’ side, they are really thirsty and they send their roots out in search of water. They will go to the nearest irrigation and drink from there, robbing water from the tree you are trying to water. They are also allelopathic, meaning that they produce a substance that discourages many other plants from growing, or growing successfully, under or near them. Their root mass is so thick close to the surface that very few plants can survive. If planted in the wrong spot they will block views, hang over the house, drop those leaves, peels of bark and depending upon the species, heavy branches, where you don’t want them, get into overhead wires or underground leach lines, etc. They don’t make good firewood or building material, and are highly flammable. How does the tree weigh in? Usually eucalyptus are all negatives in my book. Only if they are providing the only shade and bird perches for a property are they useful. Even then I recommend pollarding them (reducing their height) and trying to ‘nursery in’ other better trees to take their place. Cut trees then should be buried, as in hugelkultur. So evaluate what you have using the three positives rule and don’t be too sentimental if you don’t like something. Do you like them? If not, cut them and bury them to fertilize plants that will serve you, and yes, aesthetics is very much a plus. If you love a particular plant, then if its possible, plant it.

If you have a property that is a blank slate, your irrigation diagram will follow your plant design. If you have an existing landscape, as I had, you need to map out where all the trees and groupings of plants are, what their water needs are and keep in mind the way water runs past these plants when you do. Use Google Maps. Type in your address, find your home and zero in on it until you can clearly see the boundries of your property.

At the bottom right hand corner of the screen is the key that show how many feet are in a measurement. This line may not always equal an inch, so measure it! At the lower right Google shows you a key for distance. There is a line with a number above it. This shows you how many feet are represented by that length. Don’t assume that the line is one inch! The line will adjust, so put a ruler up to the screen and measure it. I zoom out until the line is an inch long, and take that number; its just easier to compute distances using an inch rather than a fraction. You can print that diagram of your property line, which will show you which way your house sits on the property.

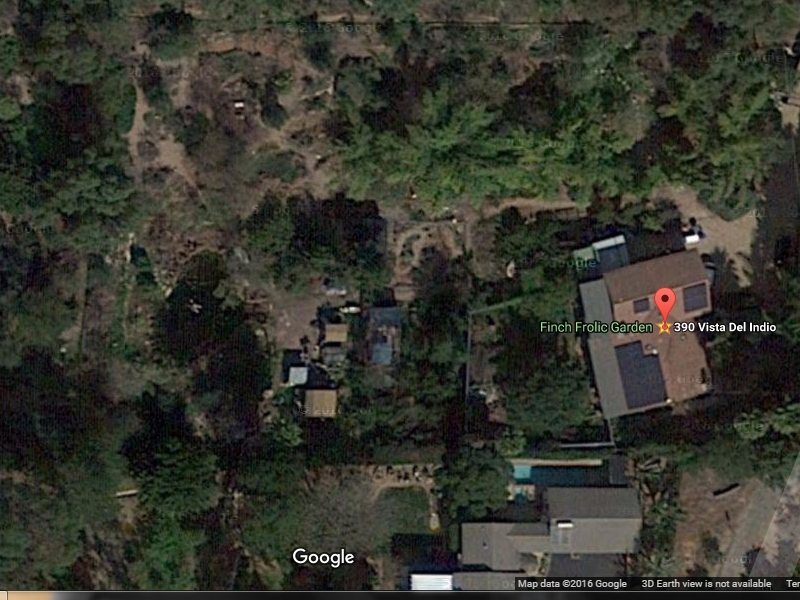

Satellite view of Finch Frolic Garden. This helps to map groupings of vegetation. I have a PC, so I press the PrntScr (print screen) key, paste it onto a paint.net screen, crop off the extra bits and print that. Now you have something to work with. I double or triple the size of the drawing onto a larger sheet; this can be done easily with a ruler, using the printed sheet to guide your angles.

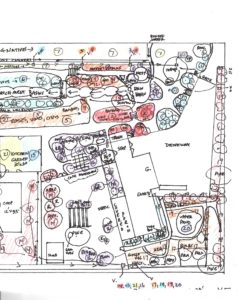

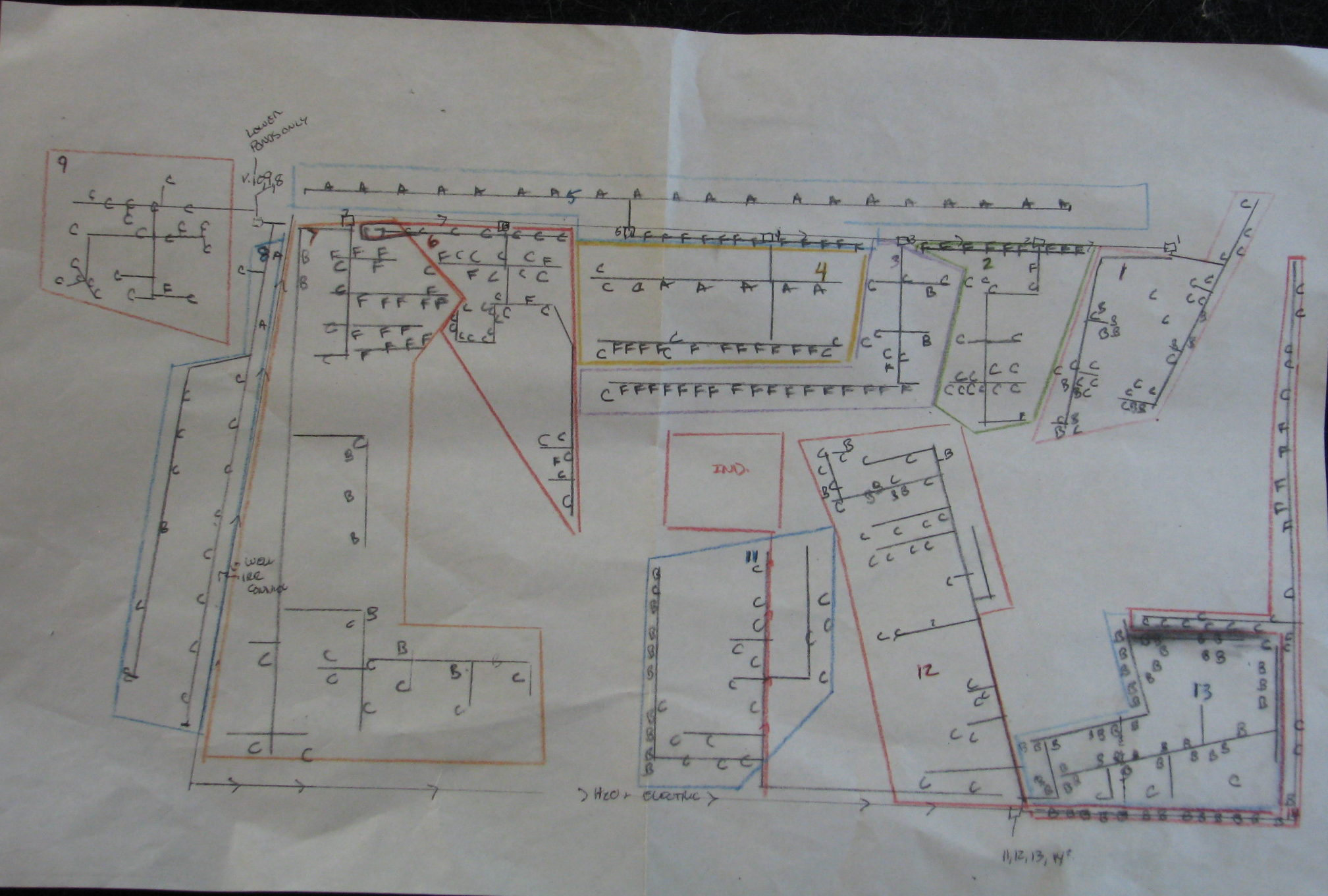

A projected irrigation plan for Finch Frolic Garden. What you actually put in may differ. Make a couple of copies of this template, and then use one to start drawing.

When you have the plants down on paper, then start with the irrigation. Determine where your water main is, and where any valves and hose bibs are around your house. If you only have domestic water to choose from, you’ll be coming from a domestic line.

Fifteen to twenty sprayers are good per valve. I’m not talking about high-pressure nozzles that shoot water all over the place; these you want to eliminate. Most of that water is evaporated.

The sprinklers that we installed have a spray of up to 4 feet, and can be reduced down to a drizzle.

These are what we installed here:

The 3/4″ T was glued in facing sideways rather than straight up. A black Street 90 and a white Street 90 were screwed into the T, firmly but with enough leeway to turn if pushed. Black ones don’t need pipe tape because they are soft and self-seal. The risers (nipples) are 6″, and were taped at both ends before screwing into the Street 90. (You don’t put the heads on yet because you’ll want to ‘blow’ out your system with water to clean the pipes beforehand. )

These risers can bend! With this configuration the risers are resistant to damage from being kicked, from having 100-lb. tortoises crawling over them, etc.

Gamera enjoying the movable sprinklers. They can be moved in all directions so that you can deliver water closer to small rooted new plants, then move them away as the root ball grows. If you have the assembly ready when you glue in the T, then you won’t have to struggle to screw it on. Ends will have a slip/thread elbow glued sideways with the same assembly.

There are lots of sprinkler heads out there. These sprayers have threaded ends rather than barbed, so that they stay in place rather than be blown off. These are 360 degree sprayers; you can obtain threaded sprayers for 180 and 90 degree, and probably other configurations as well.

A 180 degree head. Notice all the white? That is mineral deposit, and the sprinkler has run only about 10 -15 times. Don’t forget the filter. A filter in every head saves you a lot of grief with plugged heads and poor irrigation down the line. They are easy to clean.

Next post: Concluding the project.

You can read Part 1 Options here, Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, and Part 4 Conclusion here.

- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Water

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 2: Evaluating your System

Miranda in the roses gluing pipe. If you have an existing irrigation system that works, you may easily convert it by adapting the heads for whatever you want to plant. Many lawn conversions I’ve designed utilize the existing spray system, particularly for natives, but with a different watering schedule. Don’t spend money when you don’t have to.

If you have an old grove that is to be converted and downsized, you’ll usually have far more pressure in your system than you need for smaller heads which may cause them to blow. Working with an irrigation specialist for the valves and pressure is advisable. For this re-irrigation project of Finch Frolic Garden, I found Vista-based John Taylor of Taylor-Made Irrigation and Landscape, 760-945-0118. He’s the first person to listen to and consider what I have to say, based on my experience with the old system, and he adapts to different situations. I’ve learned some cool new things that I will pass on to you, and he’s enjoying learning permaculture techniques, which will help both him and his landscape clients.

Here’s a little world-weary advice from someone who trusts too easily: Many professionals no matter what their field have one set way of doing things that they apply to every situation, be it irrigation, plant selection, tree trimming, construction, etc. (My neighbor has his poor coral tree topped every year. Topping trees is a bad practice. When I asked him about it, he said that his tree trimmer has been topping trees for years and recommends it, so he’s talking his expert advice! Do you see the problem here?) You, I’m sure, have dealt with these people too. Every situation needs a different solution, so look for someone who is flexible, listens to you, can offer several solutions with various price ranges, and who will give you a detailed estimate up front. Jobs will always run over, but they shouldn’t run too much over and the professional should be determined to keep on budget, and honest with you when there is an overrun. If you ask a professional to do extra things, the new tasks will need to be added on to the original contract because it will take up part of the time allocated towards the original project, so the project completion date will be moved ahead, and will add on to the total cost. On the other side, if your professional adds on projects that he thinks you’ll like, and you give him the verbal okay, realize that he’ll be working on those projects in addition to the original tasks, so it will take longer and cost more than the original contract. Look for people who don’t consider telling you their life story part of the time for which you are paying. If you tell them your life story, remember that they are on the clock and you are paying for that time. (I’d rather deal with a quiet, focused professional than a chatterbox who will talk more than work. If he’s not talking to you, he’s probably on his phone a lot while on the job.) Look for neat vehicles with organization, letterhead for estimates and invoices, someone who shows up on time when they say they will, and stays until they are done. They should schedule in their lunch; if they work through it they are not going to work well for you later in the day, and its unprofessional. Its okay for professionals to handle several clients at one time, but only if they are well organized and are eager to finish your project on your timeline. Contractors are infamous for tearing something apart the first day, then disappearing for days or longer holding you hostage while they work on other projects. Its okay to ask about all of this, and really important to read reviews. Don’t always rely on people your friends have recommended; I’ve had both really bad and really good referrals, so make up your own mind.

Extreme mineral buildup in a PVC pipe. Photo from http://www.marinechandlery.com/. Back to irrigation. Most irrigation is PVC, the white plastic pipe. If you have old buried metal pipes they should be examined for leaks. Mostly they will fail to function due to mineral buildup due to our hard water. The inner diameter of the pipe closes; if you’ve ever cleaned your shower head or seen house drains with the thick white inner coating, that’s what I’m talking about. It will slowly dissolve in vinegar, but the vinegar must remain in the pipe to soak it for awhile, then blown out an open riser to get rid of the chunks. All sprinkler heads must be decalcified as well. Often the buildup is so old that the pipes are deteriorating and just need to be replaced, usually with PVC. The galvanized pipe can either be left in the soil to gradually rot, which is fine, or else be dug up and sold for scrap. The labor cost involved with digging it up will probably be more than what you’ll get for scrap.

Here’s some understanding of water. The reason why domestic (potable) water is chlorinated is not to purify the water. That has already been done before it gets into the delivery pipes. It is to keep biomass from forming inside the water pipes. Biomass is any type of growth that forms, usually in wet conditions. Think of algae inside a fish tank or on the inside of a pool. Biomass is nature’s way of filtering and softening hard surfaces, and in nature is essential. In man-made pipes, the biomass can not only harbor things that can make humans sick, but also slows the flow of water. Garden hoses have some biomass inside of them, and any rough part will slow the water pressure. Lengths of any kind of pipe are the same. The longer the pipe, the slightly less pressure you’ll have. Pressure is important because you want your sprinkler heads to spray, not just dribble (unless you set them for dribbling). Pressure regulators are set in sprinkler heads, Netafim, and valves to keep lines from blowing out under normal pressure. If you don’t have an irrigation system set up for a large grove or large grasslands for animals, which require enough pressure to shoot water great distances, then you shouldn’t worry about the lines blowing out. But understanding about pressure and the effects of biomass and distance will determine what size pipe you lay.

Most people use domestic water for irrigation. Some rural areas have agricultural water available for commercial growers. Some people have well water, which is what I have. Well water has not been treated, so whatever has leached into that water is what you are delivering to the topsoil. Have your well water tested for contaminants and salts. You should have a filter after the pump on your well. However, our heavy-mineralized water will form a oozy barrier around the diaphragms in valves. If debris or too much of this slick mineral buildup accumulates, the valve won’t ‘seat’, or seal, and will allow some water to seep through the pipes even when the valve is off. This has been a huge problem here at FFG, and one which several irrigation ‘specialists’ have completely denied. They deal with treated water rather than well water, and just don’t understand. Some valves have diaphragms that can be very carefully cleaned and replaced, but not frequently before they are damaged. If you have a well, check with an irrigation specialist who has real-time experience with well water and valves to recommend the appropriate valves and filter system for you. I’ll talk more about the ones John recommended for FFG in a later post.

Large-diameter pipes will carry lots more water more slowly. Small-diameter pipes carry less water more quickly. If you lay out large diameter pipes from your valves, let’s say 1″ pipe like we’re using at FFG, then you can reduce the size of your pipe gradually to your sprinkler heads and that will be the best of both worlds. You will have volume of water and increased pressure. So John has recommended that we use 1″ PVC from our valves, which are connected to the well with 1″ PVC already.

One-inch PVC runs from the valve. Then we reduce the pipe to 3/4″ at the nearest T, or closest to the first sprinkler head.

The one-inch pipe is then reduced to 3/4″ pipe at the first T, close to the first sprayer. Then the sprinklers are reduced down to 1/2″. Since our well is at the bottom of our slope and water needs to be pumped back to the top, this design really helps keep the topmost systems pressurized.

This sprayer is reduced from 3/4″ to 1/2″. So as you are laying out your garden and irrigation system, understand about slope, water pressure, volume of water and your water source. These factors all have large parts to play in the long-term success of your irrigation.

Next time I’ll discuss drawing up an irrigation plan.

You can read Part 1 Options here, Designing Your System Part 3 here , and Part 4 Conclusion here.

- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 1: Options

This tubing is so easily nicked that weeding around it often results in a bad leak that isn’t detected for awhile. Leaks cause flooding with dry areas past them on the line. A previous draft of this post was about 2,000 words of mostly rant against Netafim, so I’m starting over trying to be more helpful. You’re welcome.

In Southern California, and many dryland areas, if you are to grow food crops you have to irrigate. I have met several people who believe that they can ‘dry farm’ crops such as grapes here, and that is problematic. Even in Central California where they receive many inches more rain than we do, farmers struggle in the long hot, dry summers.

There are many ways to water, and I’ll address as many as I can.

The first and most important step for irrigating your property is installing the earthworks that will harvest what rain we do receive and allow it to percolate into the soil. Paring that with burying wood and other organic material to hold that water, planting in shallow depressions rather than on raised mounds and sheet mulching will greatly increase the health of your plants and decrease your water bill.

For delivering captured or purchased water you’ll need some kind of tubing and a force to deliver the water. We’ll discuss the natural methods first:

Ollas (oy-ahs) should have a lid or stone or something to block the top, to keep creatures from falling in and drowning. Photo from link page. For small yards, or for orchards with lots of labor, burying ollas (porous clay pots) in the center of a planting area is a wonderful idea. There is a really good article with diagrams and suggestions here. You can manually fill the ollas by carrying water to them (the best would be from rain barrels), or dragging a hose around to fill them. Or they can be combined with a water delivery system of pipes as discussed below. Water is then drawn through the porous pots by the dry soil around them, and thus to plant roots. There is a tutorial about making inexpensive ollas from small clay pots, and interesting comments, here. There are problems, but then, there are problems with everything. Clay pots can break, especially if you have soil that freezes or foot traffic. A larger pot doesn’t mean that water will be delivered farther underground; absorption is based on soil density. This is a system that you need to monitor and replace periodically. On the plus side, clay is natural and will decompose in the soil. Many years ago, long before I ‘discovered’ permaculture, I buried gallon milk jugs in which I punched small holes by some trees beyond any irrigation pipes. I didn’t know about ollas then; I just thought it was a good idea to get water close to the roots of the plants. This really worked and those trees are mature and still exist almost thirty years later, and still don’t have irrigation to them. However, I found that the plastic milk jugs become brittle and break apart, as will plastic soda bottles, and you really don’t want to bury plastic. Clay is much better.

Clay pipe photo from Permanomades. Please follow link to website. These look very large, but are not. Next would be delivering water via some kind of pipe. Clay pipes are the most natural, but unless you have the clay, the labor and the time to create lots of long, hollow clay pipes, this is a pricey option. Clay pipes break easily, too.

Split bamboo delivers water downhill. Photo from link page. If you have lots of bamboo you can season it, split it, remove the nodes (partitions) and then mount it to deliver water to individual plants, to ollas, or to swales. Again, you need time, bamboo, labor and some expertise. There is a good article about it here.

Plastic:

There are a lot of plastic pipes out there, and although I hate to invest in more plastic, it is often a necessary evil. Drip irrigation comes in many forms. There are bendable tubes that ooze, tubes that have holes spaced usually 12″ or 24″, tubes that can be punctured and into which spray heads are inserted, and tubes which can support spaghetti strands that are staked out next to individual plants. The popularity of drip irrigation has been huge in water-saving communities. Unfortunately they have lots of problems. Here I’ll indulge in just a little rant, but only as an illustration.

One of the big problems with flexible tubing in arid areas is the high mineral content of the water and what it does to these tubes. Any holes -including those in small spray heads- will become clogged with minerals.

A nozzle that is clogged next to a hole that is not. Flushing the system with vinegar works for a short time, but eventually the minerals win. If the tubing is buried, then it is virtually impossible to discover the blocked holes until plants begin to die. Tubing above ground becomes scorched in the sun and breaks down.

Also, flexible tubing is extremely chewy and fun with a little drink treat as a reward.

Coyotes and many other animals find flexible pipe so fun to chew. This is the opinion of gophers (who will chew them up below ground and you won’t know unless you find a flood or… you guessed it… dying plants), coyotes (who will dig the lines up even if there is an easier water source, because tubing is fun in the mouth), rats (because they are rats), and many other creatures. Eventually a buried flexible system will be overgrown by plant roots, will kink, will clog, will nick (and some products such as Netafim seem to nick if you even wave a trowel near it), and will be chewed. Some plants will be flooded; others will dry up. You will have an unending treasure hunt of finding buried tubing and trying to fix it, or sticking a knife point into the emitter holes to open them up and then having too much water spray out.

Plus, drip irrigation is not good for most landscape plants. Most woody perennials love a good deep drink down by their roots, and then let go dry for a varying time depending upon the species, weather and soil type. Most native California plants hate drip irrigation. According to Greg Rubin, co-author along with Lucy Warren of The California Native Landscape (Timber Press; March 5, 2013) and a San Diego native landscaper, native plants here enjoy an overhead spray such as what a rain storm would deliver. Some natives such as Flannel Bush (Fremontia) die with summer irrigation and are especially intolerant of drip. Drip is most appropriate with annuals or perennials that have very small root bases and that require regular watering. Small root balls are closer to the hot surface and will dry up more quickly. Vegetables, most herbs and bedding plants can use drip. Plants that have fuzzy leaves that can easily catch an air-born fungal disease such as powdery mildew are better watered close to the ground rather than with an overhead spray of chlorinated water.

Then there is PVC, the hard, barely flexible pipe that is ubiquitous in landscaping for decades. PVC is hard to chew, can be buried or left on the surface if covered with mulch (to protect from UV rays), is available in a UV protected version if you want to spend the extra money and still give it some sun protection, utilizes risers with larger diameter water deliver systems such as spray heads, bubblers, and even drip conversion emitters that have multiple black spaghetti strands emerging from them like some odd spider.

At Finch Frolic Garden I had taken advice to install Netafim, a brown flexible tubing with perforations set 12″ apart, which was buried across the property from each valve box. It has been a living nightmare for most of that time. Besides all the reasons that it could fail (it did all of them) listed above, it also at its best delivered the same amount of water to all of the plants no matter what their water needs. It was looped around most trees so that the trees would receive more water, but since then roots have engulfed the tubing, cutting off the water flow. There are areas with mysterious flooding where we can’t trace the source without killing many mature plants.

Over the past year we’ve lost about 1/4 of our plants including most of our vegetables, because we plant where there should be water, and then mysteriously, there isn’t any. Flushing with vinegar helped a little, but whatever holes are still functioning are closing up with mineral deposits. Okay, I’m ranting too much here. But this was an expensive investment, and an investment in plastic, that has stressed me and my garden. So upon weighing all my alternatives I’ve decided to install above-ground PVC with heads on risers that either spray or dribble, and the dribblers will go into fishscale swales above plants.

Twenty-foot lengths of PVC can fit in the Frolicmobile, and sure beats carrying it down the property. In the next few posts in this series I will talk about how to draw up an irrigation plan, installation, valves and other watering options, as Miranda and I spend our very hot summer days crawling through rose bushes and around trees gluing, cutting, blowing out and adjusting irrigation. Thanks for letting me vent.

You can read Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, Designing Your System Part 3 here , and Part 4 Conclusion here.

-

Ducklings!

Mrs. Mallard returned today, introducing her very young ducklings to our pond! Mrs. and Mr. Mallard really love our pond, and have adopted us for several years. She had tried to nest on land here, even up by our garage which is a long walk from the pond, but the eggs were always destroyed in the night. Last year she returned with four young, which all disappeared quickly. They were probably food to bullfrogs, birds, rats or other creatures. It was very sad.

Some are standing on lily pads!!! This year Mrs. Mallard went through her usual breeding time with Mr. Mallard, then disappeared, and then reappeared without ducklings. We figured that her brood hadn’t been successful and that was that for this year. Mr. Mallard has been losing his mating plumage, and she hadn’t been visiting. Miranda and I figured that she was enjoying herself elsewhere. Today as I worked outdoors I passed by the pond and to my astonishment there was Mrs. Mallard and seven adorable ducklings! These babes are only a few days old. She would have had to lead them walking from wherever her nest was, and somehow navigate a chain-link fence! At first she was cautious because I was talking to her excitedly and taking photos.

She watched me carefully, but then decided I was still safe and led them ashore. I calmed myself down and went about my work, and on one of my trips past the pond she gave me a decided look and then quickly led her brood out of the big pond just in front of me and paraded them across to the little pond. The babies had their first sample of duckweed.

Mrs. Mallard and Ducklings

Mrs. Mallard decides I’m still a friend and leads her ducklings from the big pond to the small pond at Finch Frolic Garden. I think she was showing her firs…

As these ponds have no chemical treatments, are topped off with rain and well water and cleaned by the plants and fish, the water is wonderful for wildlife. They can bathe, eat and drink without ingesting or absorbing chemicals. Good water is as microbially diverse as good soil, and all those microscopic critters are food, protection and healthy flora for all the creatures that flock to these ponds.

Later I noticed her crouched in the bog by the big pond, with all of her young out of sight underneath her. I looked around for a predator, but saw that Mr. Mallard was on the duck island and she was uncertain of him. I stood watching them, ready to protect her. Finally he noticed her, and all went well. A little later they were sitting together, still with no babes in sight.

The ducklings are safely tucked under mama in case dad has other ideas. I heard him fly off, probably to join some other males for some companionship.

Mrs. Mallard led her young across the pond and right to the floating duck island that is anchored in the middle of the pond.

Mrs. Mallard heads for the duck island for the evening. Smart mama! This island has a board down the middle and loose plants stuck in without soil. It is a remediation float as well, cleaning the water as it floats.

Everything is so new, especially this island! Miranda and I were worried that the little ducklings wouldn’t be able to get aboard the raft, but they had no trouble.

This little one is so tempted to get back in the water, but he or she resists. Its been a tiring day.

Taking a last longing look at the water, which he only learned the existence of today.

The ducklings are in an array of colors, from light yellow and grey to all dark.

Almost everyone is tucked under for the night. After exploring a little, falling off a few times and grooming themselves, they tucked under their very good mama for a warm and safe sleep. Squeee!

Safely afloat, Mrs. Mallard and children are tucked away for the night, safe from coyotes, raccoons, rats and snakes. - Building and Landscaping, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Using Pathways For Rain Catchment

Here in the drylands of San Diego we need to be especially sure to catch whatever rain may fall. Building good soil is vital for the entire planet because humans are going through decent topsoil like nobody’s business. Here at Finch Frolic Garden we’ve sheet mulched around trees to replicate decades of leaf drop, and on pathways to block weeds, prevent compaction and create good soil for shallow plant roots. We’ve also continued making our pathways work more for us by burying wood (hugelkultur) in the paths themselves. Most of our soil here is heavy clay, so creating drainage for roots is imperative. In sandy soils, creating more fungal activity to hold together the particles to retain water is important. We also need to store rain water when we get it, but not drown the roots of plants. This all can be accomplished by burying wood, the older the better.

Miranda and I have worked on many pathways, but for a few months this year the garden was given a huge boost forward with the help of Noel, a permaculture student and future farmer, who can move mountains in an afternoon with just a shovel.

The chosen pathways had these features: they were perpendicular to water flow, or were between trees that needed supplemental drainage, food and water access, and/or were where rainwater could be redirected. Eventually we’d like to do all the pathways like this but because of time, labor and materials we worked where it was most needed.

An area that becomes flooded when we have a deluge. The existing sheet mulch was pulled aside. Sections of the pathways were dug up (Noel’s work was very neat; my work is usually much less so). Wood was laid in the hole, and layered back with the dirt.

The pathway dug up and wood being layered. The nice, neat hole is Noel’s doing, not mine. Notice I said dirt, not soil. We don’t want to disturb good soil because we’d be killing microbes and destroying fungal networks. Dirt is another story; it needs amendment. As we’ve already buried all of our old wood, we timed these pathway ‘hugels’ to coincide with some appropriate tree removal.

You can be creative when cutting trees and make a chair! Watch out for sap on your pants, though. Trees were cut down and some climbing roses pruned back out of the pathway, and the green ‘waste’ was used in the nearby pathways.

This euphorbia was only sucking up water and not giving back anything, so it and its friends had to go. This one had a marking like an eye on it, and I was glad to see it go… as it was seeing me! Old palm fronds went in as well. No need to create additional work – good planning means stacking functions and saving labor.

The first layer of wood is covered with dirt, and then another layer added. After the wood was layered back with the dirt, the area was newly sheet mulched. Although the pathways are slightly higher, after another good rain (whenever that will happen) they’ll sink down and be level. They are certainly walkable and drivable as is. Although the wood is green, it isn’t in direct contact with plant roots so there won’t be a nitrogen exchange as it ages. When it does age it will become a sponge for rainwater and fantastic food for a huge section of the underground food chain, members of which create good soil which then feeds the surrounding plants. Tree roots will head towards these pantries under the paths for food. Rain overflow that normally puddles in these areas will penetrate the soil and soak in, even before the wood ages because of the air pockets around the organic material.

The best part about this, is that once it is done you don’t have to do it again in that place. Let the soil microbes take it from there. Every time you have extra wood or cuttings, dig a hole and bury it. You’ve just repurposed green waste, kept organics out of the landfill, activated your soil, fed your plants, gave an important purpose to the clearing of unwanted green material, and made your labor extremely valuable for years to come. Oh, and took a little exercise as well. Gardening and dancing are the two top exercises for keeping away dementia, so dig those hugels and then dance on them!

Burying wood and other organic materials (anything that breaks down into various components) is what nature does, only nature has a different time schedule than humans do. It takes sometimes hundreds of years for a fallen tree to decompose enough to create soil. That’s great because so many creatures need that decomposing wood. However for our purposes, and to help fix the unbelievable damage we’ve done to the earth by scraping away, poisoning and otherwise depleting the topsoil, burying wood hastens soil reparation for use in our timeline.

Another pathway is hard clay and isn’t on the top of my priority list to use for burying wood. However it does repel water due to compaction and because rainwater is so valuable I want to make this pathway work for me by catching rain. I’ve recommended to clients to turn their pathways into walkable (or even driveable) rain catchment areas by digging level-bottomed swales.

Digging gentle swales along a pathway can turn it into a rain catchment system. Make your paths work for you! A swale is a ditch with a level bottom to harvest water rather than channel water. However many pathways are on slopes or are uneven. So instead of trying to make the whole pathway a swale in an established garden, just look at the pathway and identify areas where the land has portions of level areas. Then dig slight swales in those pathways. Don’t dig deeply, you only have to gently shape the pathway into a concave shape with a level bottom. The swales don’t need to connect. You can cover the pathway and swales with bark mulch and they will still function for harvesting rain and still be walkable.

Mulching over the top makes the pathway even and still functional for rain catchment. If the pathways transect a very steep slope, you don’t want to harvest too much water on them so as not to undermine the integrity of your slope. This is a swale calculator if you have a large property on a steep slope.

So up-value your pathways by hugelkulturing them, and sheet-mulching on top. Whatever your soil, adding organics and mulching are the two best things to do to save water and build soil. And save the planet, so good going!

- Animals, Culture, Gardening adventures, Humor, Photos, Ponds, Predators, Reptiles and Amphibians, Water

Turtle Recall

Howdy there — it’s Miranda popping in from the Facebook page to bring you a cool update. It’s been quite a while since my last post on Vegetariat: I mostly leave all the easy-peasy blog work to Diane while I’m concentrating on the excruciatingly complex and tiring Facebook stuff. I know, I’m a saint. Hey, did you know old Shakespeare the Bard invented the name Miranda? — it’s the feminine form of the Latin gerund mirandus, meaning “worthy to be admired”; so really I’m Saint Admirable of Vultusliber. (One in there for the dead language folks, thank me in the comments — or, you know, not.)

Today I want to tell you a story about some ponds, and some turtles, and some recollections. No elephants.

Those who visit us on the Facebook page may already know of our glee last April when a pair of Southern Western Pond Turtles (Actinemys pallida) appeared in our big pond.

Click me, I takes you to Facebook! The Western Pond Turtle group which our Southern race (I think species status for pallida is still under study) belongs to, Actinemys marmorata, is an IUCN Red List “Vulnerable” species. This listing is due mostly to late 1800s to mid-1900s overharvest for food and extensive, continuing destruction and alteration of habitat. We simply don’t have wetlands anymore. They also struggle under pressures from invasive species such as Red-eared Sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) — which will eat small pond turtles and usurp pond turtle habitat niches — and many other trials from the cornucopia of threats we offer our native species. Actinemys pallida‘s conservation status hasn’t been updated since 1996, and probably warrants at least the more critical status of “Threatened” by now.

Soooo, we were pretty excited to see not one, but two, apparently male and female judging by size, actual pond turtles in our pond. We’ve had visits from Red-eared Sliders, certainly, and captured and relocated them to sites which already have established slider populations that aren’t going anywhere. I’m afraid we haven’t the heart to kill them, so although we’re not reducing the problem, we are working to maintain an exclusive pond turtle club in our own pond.

Adorable but sadly very destructive invasive species here in California. We were even more ecstatic when the pond turtles stayed. We’d catch glimpses of one or both of them all summer, until in the fall only the small one seemed to still be around, popping up on the duck raft to catch some sun in the warm afternoons. As it got colder, we saw him less often, but every now and then, we’d come round by the pond and there’d be the quiet “ploop” of a small scaly body slipping into the water.

The April pair, however, were not actually the first pond turtles we’d ever had on the property.

Back in July of 2011, our big pond was still under construction and was just a big dirt bowl with water in it, and lots of other activity was under way around it as old building materials were being moved and the garden being shaped.

As you can see, the early pond had no habitat fit for anything except a pair of loons. (June 18, 2011) We were quite astonished, therefore, when Jacob Hatch (of Hatch Aquatics) who was managing the installation discovered a small turtle hiding in a stack of boards behind the pond. Delighted and bemused by the appearance of this usually wary and probably quite squashable reptile near our stark pond, around tractors and trucks, we examined it for injuries and to determine what species it was.

A comparison with the images and info. on the wonderful CaliforniaHerps website confirmed the stripeless turtle as a rare native Western Pond Turtle, and probably a female from the apparent concavity of her plastron (‘belly’ half of shell).

The most cursory examination, however, immediately revealed the turtle’s startling absence of a left front foot.

The wound was old and well-healed, and the turtle was admirably (Miranda-ishly) sprightly and seemingly unperturbed and unhindered by her partial flipperlessness.

Of course, we instantly dubbed the gimpy, watery, gimlet-eyed fighter ‘Rafael Sabatini’ (author of such famous swashbuckling tales as The Sea Hawk and Captain Blood). When we determined it was, in fact, a she, we respectfully redubbed her ‘Mrs. Sabatini’.

The second real Mrs. Rafael Sabatini, née Christine Dixon, I imagine to have been a person of some intelligence and depth of feeling, due to the fact that she had Rafael’s tombstone inscribed with “He was born with a gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad”, the poignant first line of his novel of the French Revolution, Scaramouche.

Our Mrs. Sabatini was certainly full of a sense of madness — at her unjust captivity! — so we quickly released her in the only place that seemed suitable and safe on the property: the small pond at the front of our house.

And that, despite our warm feelings of companionship and our admonishments to stay safe and show her face now and then, was the last we saw of the delightful Mrs. Sabatini.

Life went on, as it does. And we gained that pond turtle couple last spring, so maybe-maybe we might end up with baby turtles here down the line. A distinguishing trait of a Shakespearean comedy (rather than a history or other) is that it ends with marriage, which implies future babies: it ends in the expectation of life. And I think Mrs. Sabatini would rather like the turtle story she was involved in to be a comedy — ‘gift of laughter’ and all. I can just imagine her rusty, grudging little whistly cackle guffing out as we fade to black.

However, in January this year, we began seeing multiple turtles in the pond again, rather than simply the lone male that had lingered into the fall. We became fearful that we’d been infiltrated by sliders again, as we’d see three turtles at once sunning on the raft — a new turtle maximum, and sliders are prolific and less picky about personal space. I had trouble getting good shots to check for the clearest field marks (the rounded vs. pointed shapes of the marginal scutes over the tail) so we were feeling rather turtle-scouraged, to be frank, a little turtle-glum. It’s difficult to catch a slider, but if we had them in the pond, as we had the grim feeling we did, they couldn’t stay or we’d risk all the balanced habitat we’d built up for our native species.

“Who am I? I’ll never tell! Keh-heh-heh-heh-hui! (neck in, neck in)!” Last night I decided to start catching up on my new year photo sorting. I take a lot of photos, and they all come off the camera into my ExternalHD Limbo on my desktop, where they’re eventually sorted and distributed to their homes in various folder nestings on my external harddrives. I’d managed to grab a few shots of the January turtles, and determined to examine them as best I could for slidery traits. It was time, I felt, to know for certain.

I pulled up a photo of a chummy pair of turtles I’d taken January 17th as they enjoyed the weak sunshine on the raft.

The resolution was good, so I was able to zoom in on their faces with fair clarity. Happily, I couldn’t see any stripes, red or yellow, on the face that would indicate a slider, and their chins looked mottled-yellow as pond turtles’ do.

Looking for more clues, I panned down from the faces along the necks and shells-fronts and —

— and there it was. Or there it wasn’t.

For on the smaller turtle, who was relaxing under the friendly claw of its chelonian compatriot, where there ought to have been a small reptilian left front leg — there was none.

Mrs. Sabatini… had returned.

(Scaramouche, Scaramouche, she finds it difficult to do the fan-dan-go!)

“Faith, it’s an uncertain world entirely”! We certainly didn’t expect the same small, appendagially-impaired pond turtle to suddenly reappear in our pond after five years of absence.

Well, whether she’d truly been away or was simply being a lot more sneaky about using the pond so we never saw her, we’re exceedingly chuffed to know she’s back. She’s a jewel in our healthy, chemical-free habitat crown, and we’re pretty chuffed with ourselves for creating a safe, natural pond that she and her buddies — and so many other water-dependent species — can rely on.

If you build it, they will come — and come back!

Let’s keep making habitat for the small, wild, heart-pirating creatures in our lives, eh?

(Please direct Mrs. Sabatini fanmail c/o Finch Frolic Garden.)

M