- Bees, Compost, Frost and Heat, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Shade

In drylands there is a noticeable lack of trees. This situation is kind of a Catch-22. The hotter and drier it is, the less water there is in the ground to provide for plants that can attain height, and the more the leaves of the existing trees must adapt (become smaller) to prevent transpiration and sunburn. Yet the very lack of trees and their extensive root systems, and the shade and habitat they create, and the transpiration that allows humidity to keep the air moist for pollen to survive, is one of the causes of desertification.

In drylands there is a noticeable lack of trees. This situation is kind of a Catch-22. The hotter and drier it is, the less water there is in the ground to provide for plants that can attain height, and the more the leaves of the existing trees must adapt (become smaller) to prevent transpiration and sunburn. Yet the very lack of trees and their extensive root systems, and the shade and habitat they create, and the transpiration that allows humidity to keep the air moist for pollen to survive, is one of the causes of desertification.So how do we stop this cycle?

First, work on a manageable area. If you have a large property, then start on the area closest to your home or where you need water the most, or where water settles. As in the Annie Lamont title, Bird by Bird, you work on a piece a little at a time.

- Put in earthworks to harvest rainwater. Simple swales or rain catchment basins, perpendicular to the water flow and on contour with your property, will harvest hundreds of gallons of water each rain. You can do them with tractors, you can do them with shovels, you can do small ones with trowels above small plants. Just do them.

- Bury organic matter: hugelkultur. Do you have old wood laying around? Palm trees that are growing and being a fire hazard? Old untreated lumber full of nails? Branches? All of this can be layered into the ground. Bury organic matter downhill from your swales. If you cannot bury, then pound sticks vertically into the ground. The important thing is that you are adding organic material back into your depleted soil. It will hold rainwater, it will activate soil microbes and fungi, it will open oxygen and nutrient channels, it will sequester carbon and make it available to the plants. Our soil is mostly just dead dirt. By layering organic material with dirt you are doing what nature does, but at an accelerated pace.

If your soil is unmanageable, or you can’t dig, then layer on top of the soil. Its called, among other things, lasagne gardening. Lay out newspaper, top it with fresh grass clippings or other greens, top that with dried grass clippings, dried leaves or other ‘brown’ materials, and depending upon what you want to plant in this, you can top it with mulch or with a layer of good compost and then mulch. Then plant in it! You create soil on top of the ground.

If your soil is unmanageable, or you can’t dig, then layer on top of the soil. Its called, among other things, lasagne gardening. Lay out newspaper, top it with fresh grass clippings or other greens, top that with dried grass clippings, dried leaves or other ‘brown’ materials, and depending upon what you want to plant in this, you can top it with mulch or with a layer of good compost and then mulch. Then plant in it! You create soil on top of the ground. - Mulch and sheet mulch! Protect your soil from the heat and wind, and from pounding rain. A thin layer of bark will actually heat up and accelerate the evaporation process: add several inches of mulch to the ground. Better yet, sheet mulch by laying cardboard and/or newspaper directly on top of the weeds and layering an inch or more of mulch on top.

This can be free mulch from landscapers, old weeds, grass clippings, animal bedding, softwood cuttings… just cover the soil to keep it moist and protected. Thick mulching alone will help keep some humidity in the air and begin soil processes, as well as reduce evaporation by reflected heat that comes from bare earth or gravel.

This can be free mulch from landscapers, old weeds, grass clippings, animal bedding, softwood cuttings… just cover the soil to keep it moist and protected. Thick mulching alone will help keep some humidity in the air and begin soil processes, as well as reduce evaporation by reflected heat that comes from bare earth or gravel. - Plant native plants. They thrive in our soil. Grow trees that filter the sun and don’t like a lot of water, such as palo verde, or those that take minimal additional water such as desert willow, California redbud, valley oak, or others. Grow tall bushes such as toyon, lemonadeberry, sugarbush, quailbush, ceanothus

or others. Use these wonderful plants to invite in birds,butterflies, lizards and other wildlife that will begin pollination and help activate the soil.

or others. Use these wonderful plants to invite in birds,butterflies, lizards and other wildlife that will begin pollination and help activate the soil. - Design your garden for what you want to grow besides natives. Fruit trees? Vegetables? Ornamentals? They can be arranged in your mulched area in guilds to grow cooperatively.

- Grow shade. Fast-growing trees and shrubs are invaluable for protecting – ‘nurserying in’ – less hardy plants. Acacia and cassia are both nitrogen-fixers and will grow quickly to shade your plants, can be cut for green waste in the fall and also attract pollinators. Moringa is completely edible and is also an excellent chop-and-drop tree. There are many others. You need to protect what you plant from the harsh summer sunlight, and using sacrificial trees and shrubs is the most productive way to do it.

- Protect your tree trunks from scorching by growing light vines up them, such as beans or small squash.

Once you have done this process in one area, then move on to the next, like a patchwork quilt. These areas should all be planted in accordance with a larger plan that covers your entire property, so that you plant what you want in the best possible place. However, the earthworks, hugelkultur and mulching can be done everywhere. By following these guidelines, and working one small area at a time, you’ll have success, have trees, shade, food and be helping reverse desertification, one plot at a time.

- Animals, Arts and Crafts, Bees, Birding, Building and Landscaping, Chickens, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Photos, Ponds, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Six Years of Permaculture

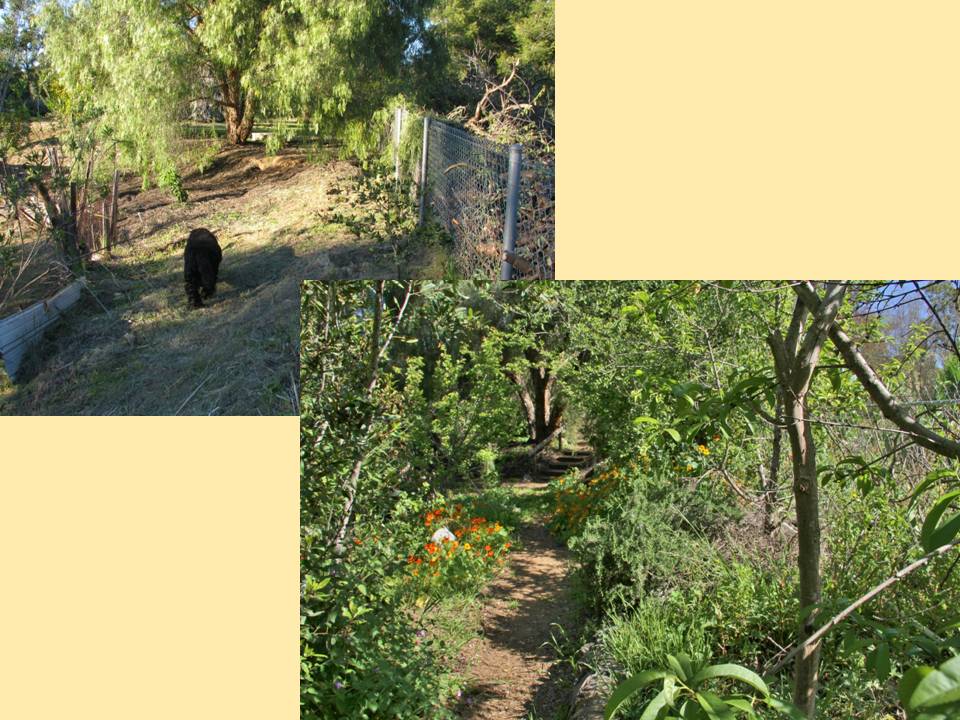

In February, 2011, I signed the contract with Roger Boddaert to create a permaculture food forest. The goals at that time were to stop the erosion on the property, to create a wildlife habitat, and to grow food, medicine, native plants, building materials, herbs and ornamentals in a sane way: no chemicals. So the journey began, and it hasn’t been easy. Nor did I at that time know that the garden would evolve into Finch Frolic Garden and my business would be education.

In February, 2011, I signed the contract with Roger Boddaert to create a permaculture food forest. The goals at that time were to stop the erosion on the property, to create a wildlife habitat, and to grow food, medicine, native plants, building materials, herbs and ornamentals in a sane way: no chemicals. So the journey began, and it hasn’t been easy. Nor did I at that time know that the garden would evolve into Finch Frolic Garden and my business would be education. In preparing for a talk about our garden, Miranda and I worked on before and after photos. The garden this April, 2017, is stunning, with blooming wisteria, fruit trees, red bud, roses, angel-wing jasmine, iris, and so much more. Best of all Mrs. Mallard has brought her annual flock of ducklings from wherever she nests, and the four babies are still alive and thriving after a week! So I thought I’d share the incredible difference between what had been, and what is now. All done with low water use, no fertilizer, herbicide, insecticide, additives or supplements. Come visit when you can! Slideshow images change in ten seconds:

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Natives, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Rain Catching, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Installing a Swale

Last Saturday we hosted our first workshop of 2017, featuring Alden Hough of Sky Mountain Permaculture. Alden is a master at creating earthworks, and he spent three hours here at Finch Frolic Garden teaching a class of sixteen people how to install swales correctly.

Last Saturday we hosted our first workshop of 2017, featuring Alden Hough of Sky Mountain Permaculture. Alden is a master at creating earthworks, and he spent three hours here at Finch Frolic Garden teaching a class of sixteen people how to install swales correctly.  The project was a small pond that overflowed and flooded when heavy rains hit. The soil is heavy clay and therefore the small pond doesn’t percolate. It is kept filled by the well, and its overflow feeds the bog and the big pond. Right now the little pond is full of native Pacific chorus frog tadpoles, which will evolve into small frogs that will go out into the landscape and eat bugs the rest of the year.

The project was a small pond that overflowed and flooded when heavy rains hit. The soil is heavy clay and therefore the small pond doesn’t percolate. It is kept filled by the well, and its overflow feeds the bog and the big pond. Right now the little pond is full of native Pacific chorus frog tadpoles, which will evolve into small frogs that will go out into the landscape and eat bugs the rest of the year. He created a urbanite (cement chunks) spillway into a twenty-foot swale. The class learned what a bunyip was and how to use the water level, and how to use a laser level. The swale will hold about 300 gallons of water that would have overflowed into another area, spread and sink the water.

He created a urbanite (cement chunks) spillway into a twenty-foot swale. The class learned what a bunyip was and how to use the water level, and how to use a laser level. The swale will hold about 300 gallons of water that would have overflowed into another area, spread and sink the water.

The swale was measured and marked on contour.

Bermuda grass was pulled from it and set into trash cans to cook in the sun and hopefully be destroyed. The swale was then dug by hand.

Bermuda grass was pulled from it and set into trash cans to cook in the sun and hopefully be destroyed. The swale was then dug by hand. Old wood – branches, logs, boards and old posts – were laid below the swale, and covered by the dirt. This hugelkultur will absorb seeping water, aerate and enrich the soil, and provide food and water over time for the trees downhill.

Old wood – branches, logs, boards and old posts – were laid below the swale, and covered by the dirt. This hugelkultur will absorb seeping water, aerate and enrich the soil, and provide food and water over time for the trees downhill. More dirt was needed to cover the wood so we emptied the first rain catchment basin on the property of silt and hauled it down the hill. This was a lot of heavy work, and several of our attendees worked extremely hard with the wheelbarrows. Miranda and I have a lot of experience doing this heavy work, and we are glad that this swale project also emptied this basin.

More dirt was needed to cover the wood so we emptied the first rain catchment basin on the property of silt and hauled it down the hill. This was a lot of heavy work, and several of our attendees worked extremely hard with the wheelbarrows. Miranda and I have a lot of experience doing this heavy work, and we are glad that this swale project also emptied this basin. Our wonderful workshop attendees worked very hard in the heat. The end result was a swale of beauty.

By creating level swales dug on contour, you can see how right it looks. It hasn’t been dug deeper into the ground at one end to force the swale to be level. If you measure on contour your swale can be of any size, and it will collect, passify, spread and sink rainwater into the landscape. Earthworks are the best way to hold water, and are imperative to reestablishing water tables, keeping wells running, keeping trees alive and maintaining springs and streams. A little earthworks will make a huge difference.

By creating level swales dug on contour, you can see how right it looks. It hasn’t been dug deeper into the ground at one end to force the swale to be level. If you measure on contour your swale can be of any size, and it will collect, passify, spread and sink rainwater into the landscape. Earthworks are the best way to hold water, and are imperative to reestablishing water tables, keeping wells running, keeping trees alive and maintaining springs and streams. A little earthworks will make a huge difference.What needs to be done now is to create a dedicated overflow from the swale into the main pond. As this area receives a lot of foot traffic, we’ll also need to haul more silt to make the raised walkway more gradual and blended with the paths around. Once the tadpoles have grown and left the pond, we can drain it and use that silt. Two projects in one.

Prior to the project Miranda carefully removed a lot of healthy creeping red fescue from the work site. After the swale and spillway were dug she replanted some of it. Native yarrow will also be planted to help hold the swale.

A huge thanks to the many people who came to learn and work on site. No matter how many movies you watch or books you read, having hands-on experience makes the education click. And an extra huge thanks to Alden Hough for his expertise and hard work. Please visit Sky Mountain Permaculture in Escondido for more classes – earth bag dome building included – coming up there.

Our next Finch Frolic Garden workshop will be in April: April 22, 2pm – 4pm: The Many Benefits of Trees: Care, Nurturing and Pruning . Roger Boddaert, the Tree Man of Fallbrook and professional landscaper who planned the original garden that would evolve into Finch Frolic Garden, will talk about trees. So many trees are dying due to the drought, and we need to replace them to help shade and cool the earth and hold onto moisture. But what to plant, where and how to care for them? Roger will take you through tree care based on fifty years of experience in landscaping. Visit https://www.southernpalmetto.com/services/ and get all the details.

Go forth and dig swales!

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Earthworks Workshop

Happy March! Finch Frolic Garden is officially open, and the trees are bursting into leaf and bloom. Birds are twitterpating and the ten inches of rain we’ve received since October are slowly working through the soil thanks to our earthworks.

Here’s an opportunity to learn just how to create accurate swales and hugelkultur so that they work. Saturday March 11th from 1 -4 we have the privilege of having Alden Hough from Sky Mountain Permaculture hold our first monthly workshop here in the garden. Alden has

years of experience with building earthworks on all scales, from guiding excavators across hillsides to hand-dug. Alden will describe how to build swales and hugelkultur beds, show off equipment, and then its hands-on in the garden. You’ll learn how to use a laser level and a bunyip, and get the feel of how to build on contour. Bring your gloves and be prepared to have some fun creating earthworks, so that you can do it properly on your own property.

years of experience with building earthworks on all scales, from guiding excavators across hillsides to hand-dug. Alden will describe how to build swales and hugelkultur beds, show off equipment, and then its hands-on in the garden. You’ll learn how to use a laser level and a bunyip, and get the feel of how to build on contour. Bring your gloves and be prepared to have some fun creating earthworks, so that you can do it properly on your own property.The workshop fee is $20/person. Please RSVP to dianeckennedy@prodigy.net. Wear appropriate work clothes and sun protection. Complimentary vegetarian refreshments will be available. Attendees may stroll Finch Frolic Garden as well. Don’t wait!

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Swales and Basins in Action!

This week here in Fallbrook, CA, at Finch Frolic Garden we received almost three inches of rain in 18 hours. Our storm pattern is changing so that there are fewer rain events, but when it rains, it really rains.

This week here in Fallbrook, CA, at Finch Frolic Garden we received almost three inches of rain in 18 hours. Our storm pattern is changing so that there are fewer rain events, but when it rains, it really rains.  For many this was a flood. Precious rainwater is channeled away from properties and into the street. In permaculture gardens the water is harvested in the earth with simple earthworks such as swales (level-bottomed ditches) and rain catchment basins.

For many this was a flood. Precious rainwater is channeled away from properties and into the street. In permaculture gardens the water is harvested in the earth with simple earthworks such as swales (level-bottomed ditches) and rain catchment basins.Visitors have often expressed their desire to see the earthworks in action, so I took my camera out into the food forest.

That was when the rain gauge was at about two and three quarters, with more to come. (I wanted to photograph the garden after the storm had passed but my camera refused to turn on due to the indignity of having been wet. A couple of nights in a bag of rice did it wonders.)

That was when the rain gauge was at about two and three quarters, with more to come. (I wanted to photograph the garden after the storm had passed but my camera refused to turn on due to the indignity of having been wet. A couple of nights in a bag of rice did it wonders.)

Please excuse the unsteady camerawork, and my oilskin sleeve and dripping hand making cameo appearances in the film. I was using my hand to shield the lens from the rain.

- Animals, Bees, Compost, Gardening adventures, Irrigation and Watering, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Creating Rain with Canopy

Even if we don’t receive a lot of rain in drylands, we might have fog, sprinkles and other degrees of ambient moisture. This moisture can burn off with reflected heat from hard-packed earth, from gravel and hardscape, and from buildings. It is too irregular and thin to make the use of mist nets feasible. However, a much better way to collect that moisture and turn it into rain is the method nature uses: trees. The layers of a plant guild are designed to capture, soften and sink rainwater, so why not just let them do it? Many trees are dying due to heat, low water table, lack of rainfall and dry air. Replacing them with native and drought-tolerant trees is essential to help put the brakes on desertification.

Please take five minutes, follow this link and listen and have a walk with me into Finch Frolic Garden as this 5-year-old canopy collects moisture and turns it into rain:

Plant a tree!

- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 3: Designing Your System

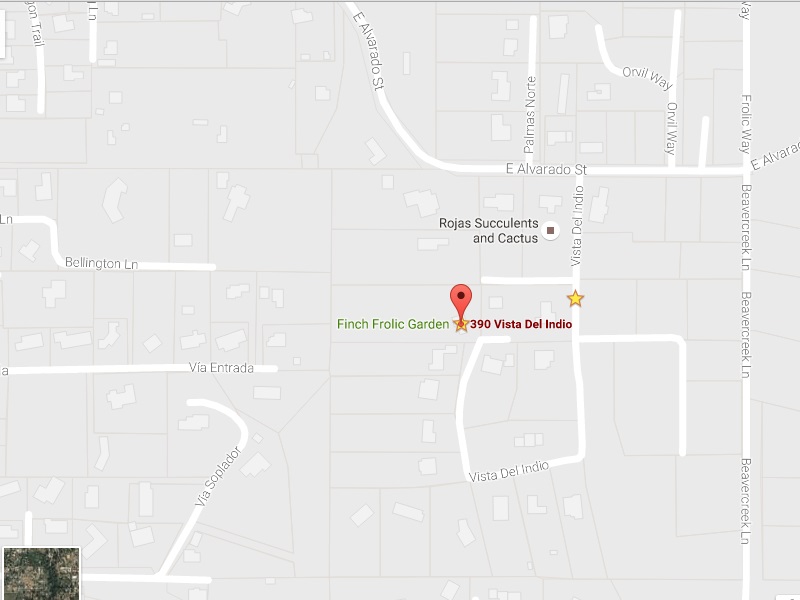

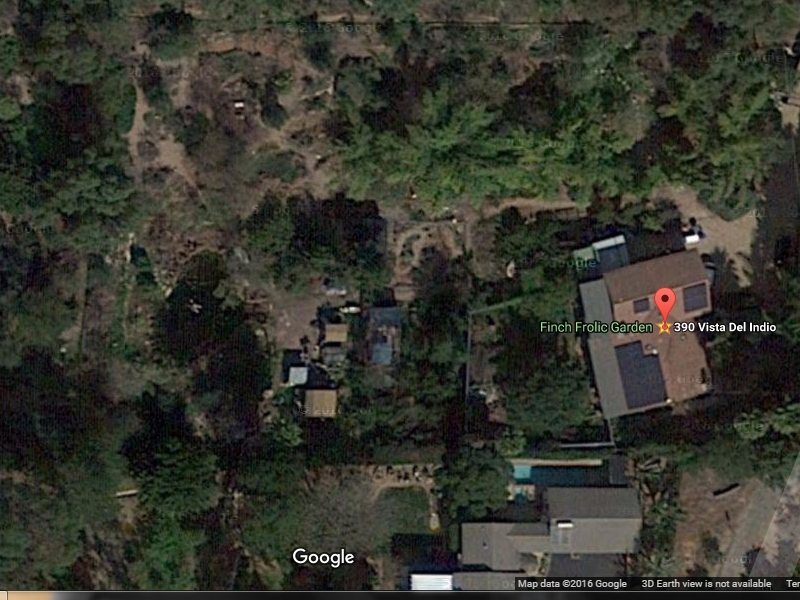

Google Maps view of property lines. Before you start buying pipe, make your design. If you are new to the property, evaluate the plants and features that exist and decide if you really want them or not. Use the ‘three positives’ rule in permaculture: everything in your yard should give you at least three positive things. For instance, you have a eucalyptus tree. It gives great shade, it is a great roost for larger birds which keep down your mice and rats, it drops lots of leaves for mulch, etc. On the ‘negative’ side, they are really thirsty and they send their roots out in search of water. They will go to the nearest irrigation and drink from there, robbing water from the tree you are trying to water. They are also allelopathic, meaning that they produce a substance that discourages many other plants from growing, or growing successfully, under or near them. Their root mass is so thick close to the surface that very few plants can survive. If planted in the wrong spot they will block views, hang over the house, drop those leaves, peels of bark and depending upon the species, heavy branches, where you don’t want them, get into overhead wires or underground leach lines, etc. They don’t make good firewood or building material, and are highly flammable. How does the tree weigh in? Usually eucalyptus are all negatives in my book. Only if they are providing the only shade and bird perches for a property are they useful. Even then I recommend pollarding them (reducing their height) and trying to ‘nursery in’ other better trees to take their place. Cut trees then should be buried, as in hugelkultur. So evaluate what you have using the three positives rule and don’t be too sentimental if you don’t like something. Do you like them? If not, cut them and bury them to fertilize plants that will serve you, and yes, aesthetics is very much a plus. If you love a particular plant, then if its possible, plant it.

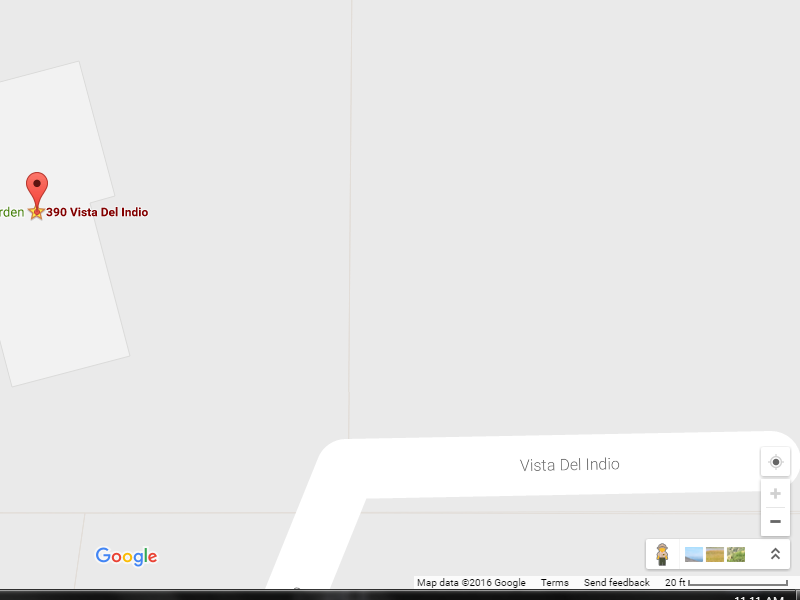

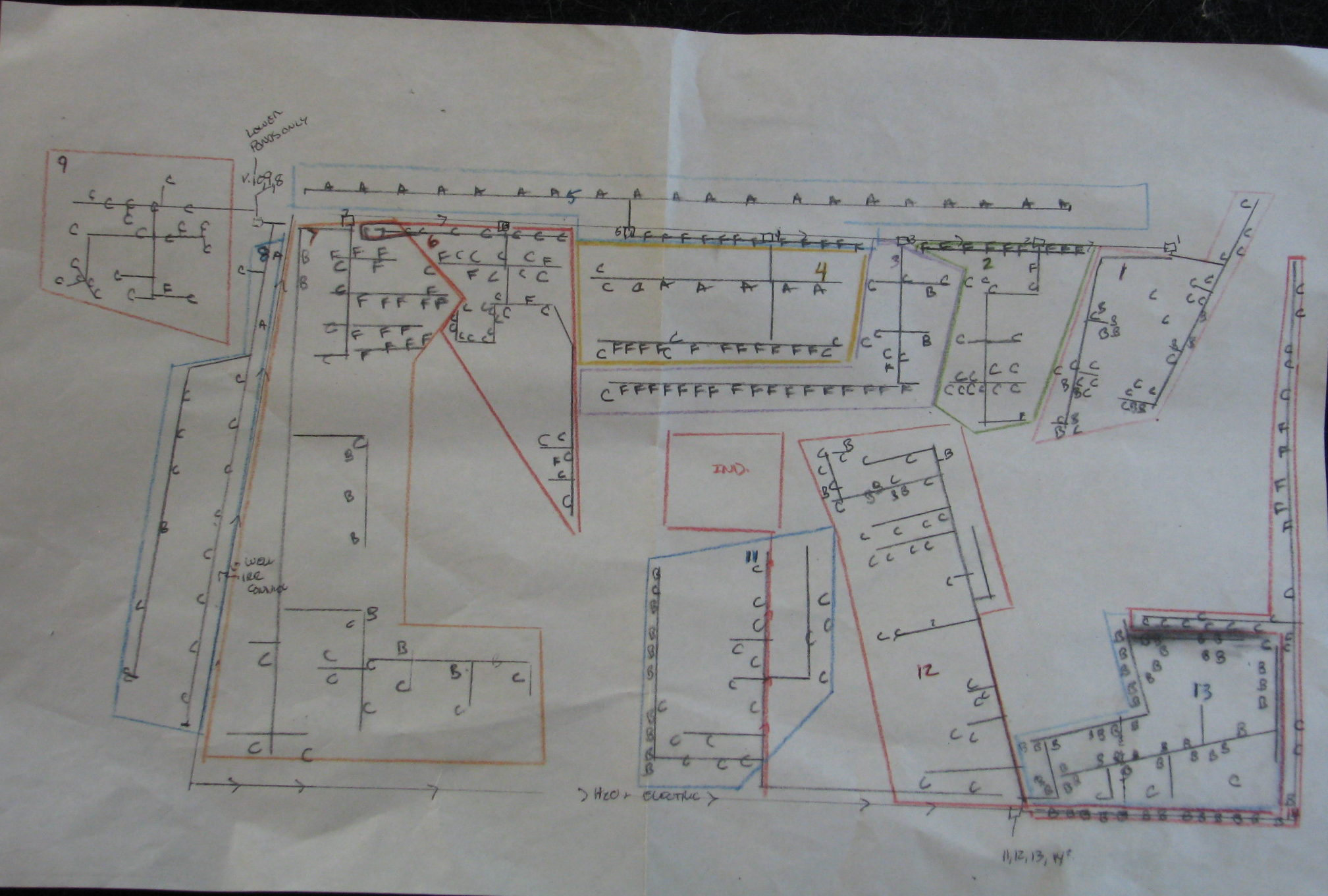

If you have a property that is a blank slate, your irrigation diagram will follow your plant design. If you have an existing landscape, as I had, you need to map out where all the trees and groupings of plants are, what their water needs are and keep in mind the way water runs past these plants when you do. Use Google Maps. Type in your address, find your home and zero in on it until you can clearly see the boundries of your property.

At the bottom right hand corner of the screen is the key that show how many feet are in a measurement. This line may not always equal an inch, so measure it! At the lower right Google shows you a key for distance. There is a line with a number above it. This shows you how many feet are represented by that length. Don’t assume that the line is one inch! The line will adjust, so put a ruler up to the screen and measure it. I zoom out until the line is an inch long, and take that number; its just easier to compute distances using an inch rather than a fraction. You can print that diagram of your property line, which will show you which way your house sits on the property.

Satellite view of Finch Frolic Garden. This helps to map groupings of vegetation. I have a PC, so I press the PrntScr (print screen) key, paste it onto a paint.net screen, crop off the extra bits and print that. Now you have something to work with. I double or triple the size of the drawing onto a larger sheet; this can be done easily with a ruler, using the printed sheet to guide your angles.

A projected irrigation plan for Finch Frolic Garden. What you actually put in may differ. Make a couple of copies of this template, and then use one to start drawing.

When you have the plants down on paper, then start with the irrigation. Determine where your water main is, and where any valves and hose bibs are around your house. If you only have domestic water to choose from, you’ll be coming from a domestic line.

Fifteen to twenty sprayers are good per valve. I’m not talking about high-pressure nozzles that shoot water all over the place; these you want to eliminate. Most of that water is evaporated.

The sprinklers that we installed have a spray of up to 4 feet, and can be reduced down to a drizzle.

These are what we installed here:

The 3/4″ T was glued in facing sideways rather than straight up. A black Street 90 and a white Street 90 were screwed into the T, firmly but with enough leeway to turn if pushed. Black ones don’t need pipe tape because they are soft and self-seal. The risers (nipples) are 6″, and were taped at both ends before screwing into the Street 90. (You don’t put the heads on yet because you’ll want to ‘blow’ out your system with water to clean the pipes beforehand. )

These risers can bend! With this configuration the risers are resistant to damage from being kicked, from having 100-lb. tortoises crawling over them, etc.

Gamera enjoying the movable sprinklers. They can be moved in all directions so that you can deliver water closer to small rooted new plants, then move them away as the root ball grows. If you have the assembly ready when you glue in the T, then you won’t have to struggle to screw it on. Ends will have a slip/thread elbow glued sideways with the same assembly.

There are lots of sprinkler heads out there. These sprayers have threaded ends rather than barbed, so that they stay in place rather than be blown off. These are 360 degree sprayers; you can obtain threaded sprayers for 180 and 90 degree, and probably other configurations as well.

A 180 degree head. Notice all the white? That is mineral deposit, and the sprinkler has run only about 10 -15 times. Don’t forget the filter. A filter in every head saves you a lot of grief with plugged heads and poor irrigation down the line. They are easy to clean.

Next post: Concluding the project.

You can read Part 1 Options here, Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, and Part 4 Conclusion here.

- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 1: Options

This tubing is so easily nicked that weeding around it often results in a bad leak that isn’t detected for awhile. Leaks cause flooding with dry areas past them on the line. A previous draft of this post was about 2,000 words of mostly rant against Netafim, so I’m starting over trying to be more helpful. You’re welcome.

In Southern California, and many dryland areas, if you are to grow food crops you have to irrigate. I have met several people who believe that they can ‘dry farm’ crops such as grapes here, and that is problematic. Even in Central California where they receive many inches more rain than we do, farmers struggle in the long hot, dry summers.

There are many ways to water, and I’ll address as many as I can.

The first and most important step for irrigating your property is installing the earthworks that will harvest what rain we do receive and allow it to percolate into the soil. Paring that with burying wood and other organic material to hold that water, planting in shallow depressions rather than on raised mounds and sheet mulching will greatly increase the health of your plants and decrease your water bill.

For delivering captured or purchased water you’ll need some kind of tubing and a force to deliver the water. We’ll discuss the natural methods first:

Ollas (oy-ahs) should have a lid or stone or something to block the top, to keep creatures from falling in and drowning. Photo from link page. For small yards, or for orchards with lots of labor, burying ollas (porous clay pots) in the center of a planting area is a wonderful idea. There is a really good article with diagrams and suggestions here. You can manually fill the ollas by carrying water to them (the best would be from rain barrels), or dragging a hose around to fill them. Or they can be combined with a water delivery system of pipes as discussed below. Water is then drawn through the porous pots by the dry soil around them, and thus to plant roots. There is a tutorial about making inexpensive ollas from small clay pots, and interesting comments, here. There are problems, but then, there are problems with everything. Clay pots can break, especially if you have soil that freezes or foot traffic. A larger pot doesn’t mean that water will be delivered farther underground; absorption is based on soil density. This is a system that you need to monitor and replace periodically. On the plus side, clay is natural and will decompose in the soil. Many years ago, long before I ‘discovered’ permaculture, I buried gallon milk jugs in which I punched small holes by some trees beyond any irrigation pipes. I didn’t know about ollas then; I just thought it was a good idea to get water close to the roots of the plants. This really worked and those trees are mature and still exist almost thirty years later, and still don’t have irrigation to them. However, I found that the plastic milk jugs become brittle and break apart, as will plastic soda bottles, and you really don’t want to bury plastic. Clay is much better.

Clay pipe photo from Permanomades. Please follow link to website. These look very large, but are not. Next would be delivering water via some kind of pipe. Clay pipes are the most natural, but unless you have the clay, the labor and the time to create lots of long, hollow clay pipes, this is a pricey option. Clay pipes break easily, too.

Split bamboo delivers water downhill. Photo from link page. If you have lots of bamboo you can season it, split it, remove the nodes (partitions) and then mount it to deliver water to individual plants, to ollas, or to swales. Again, you need time, bamboo, labor and some expertise. There is a good article about it here.

Plastic:

There are a lot of plastic pipes out there, and although I hate to invest in more plastic, it is often a necessary evil. Drip irrigation comes in many forms. There are bendable tubes that ooze, tubes that have holes spaced usually 12″ or 24″, tubes that can be punctured and into which spray heads are inserted, and tubes which can support spaghetti strands that are staked out next to individual plants. The popularity of drip irrigation has been huge in water-saving communities. Unfortunately they have lots of problems. Here I’ll indulge in just a little rant, but only as an illustration.

One of the big problems with flexible tubing in arid areas is the high mineral content of the water and what it does to these tubes. Any holes -including those in small spray heads- will become clogged with minerals.

A nozzle that is clogged next to a hole that is not. Flushing the system with vinegar works for a short time, but eventually the minerals win. If the tubing is buried, then it is virtually impossible to discover the blocked holes until plants begin to die. Tubing above ground becomes scorched in the sun and breaks down.

Also, flexible tubing is extremely chewy and fun with a little drink treat as a reward.

Coyotes and many other animals find flexible pipe so fun to chew. This is the opinion of gophers (who will chew them up below ground and you won’t know unless you find a flood or… you guessed it… dying plants), coyotes (who will dig the lines up even if there is an easier water source, because tubing is fun in the mouth), rats (because they are rats), and many other creatures. Eventually a buried flexible system will be overgrown by plant roots, will kink, will clog, will nick (and some products such as Netafim seem to nick if you even wave a trowel near it), and will be chewed. Some plants will be flooded; others will dry up. You will have an unending treasure hunt of finding buried tubing and trying to fix it, or sticking a knife point into the emitter holes to open them up and then having too much water spray out.

Plus, drip irrigation is not good for most landscape plants. Most woody perennials love a good deep drink down by their roots, and then let go dry for a varying time depending upon the species, weather and soil type. Most native California plants hate drip irrigation. According to Greg Rubin, co-author along with Lucy Warren of The California Native Landscape (Timber Press; March 5, 2013) and a San Diego native landscaper, native plants here enjoy an overhead spray such as what a rain storm would deliver. Some natives such as Flannel Bush (Fremontia) die with summer irrigation and are especially intolerant of drip. Drip is most appropriate with annuals or perennials that have very small root bases and that require regular watering. Small root balls are closer to the hot surface and will dry up more quickly. Vegetables, most herbs and bedding plants can use drip. Plants that have fuzzy leaves that can easily catch an air-born fungal disease such as powdery mildew are better watered close to the ground rather than with an overhead spray of chlorinated water.

Then there is PVC, the hard, barely flexible pipe that is ubiquitous in landscaping for decades. PVC is hard to chew, can be buried or left on the surface if covered with mulch (to protect from UV rays), is available in a UV protected version if you want to spend the extra money and still give it some sun protection, utilizes risers with larger diameter water deliver systems such as spray heads, bubblers, and even drip conversion emitters that have multiple black spaghetti strands emerging from them like some odd spider.

At Finch Frolic Garden I had taken advice to install Netafim, a brown flexible tubing with perforations set 12″ apart, which was buried across the property from each valve box. It has been a living nightmare for most of that time. Besides all the reasons that it could fail (it did all of them) listed above, it also at its best delivered the same amount of water to all of the plants no matter what their water needs. It was looped around most trees so that the trees would receive more water, but since then roots have engulfed the tubing, cutting off the water flow. There are areas with mysterious flooding where we can’t trace the source without killing many mature plants.

Over the past year we’ve lost about 1/4 of our plants including most of our vegetables, because we plant where there should be water, and then mysteriously, there isn’t any. Flushing with vinegar helped a little, but whatever holes are still functioning are closing up with mineral deposits. Okay, I’m ranting too much here. But this was an expensive investment, and an investment in plastic, that has stressed me and my garden. So upon weighing all my alternatives I’ve decided to install above-ground PVC with heads on risers that either spray or dribble, and the dribblers will go into fishscale swales above plants.

Twenty-foot lengths of PVC can fit in the Frolicmobile, and sure beats carrying it down the property. In the next few posts in this series I will talk about how to draw up an irrigation plan, installation, valves and other watering options, as Miranda and I spend our very hot summer days crawling through rose bushes and around trees gluing, cutting, blowing out and adjusting irrigation. Thanks for letting me vent.

You can read Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, Designing Your System Part 3 here , and Part 4 Conclusion here.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Predators, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving

Polyculture In A Veggie Bed

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

By burying sticks in planting holes you are helping feed the soil and hold water. When planting veggies here at Finch Frolic Garden I often mix up a handful of vegetable, herb and flower seeds that fulfill the plant guild guidelines and plant them all in one area. They come up in a mix of heights, colors, shapes and scents to fool bugs. The result is like a miniature forest.

A merry mixture of vegetables, herbs and flowers in a mature bed. However that sort of wild designed planting has its drawbacks. Harvesting is more time consuming (although more fun, like a treasure-hunt). Many people find peace in looking at rows of vegetables, and peace is valuable.

We disturb the soil as little as possible, and pull the soil back for potatoes. You can plant polyculture in rows as well. Just plant each row with a different member of the plant guild, and you’ll achieve a similar effect with insect confusion, and with nutrient conservation.

In this small, slightly sunken bed (we are in drylands so we plant concave to catch water), we planted rows of three kinds of potatoes, two kinds of shallots, a row each of bush beans, fava beans, parsnips, radish and carrots.

Miranda planting potatoes and shallots before the smaller seeds go in. We covered the bed with a light mulch made from dried dwarf cattail stems. This sat lightly on the soil and yet allowed light and water penetration, giving the seedlings protection from birds and larger bugs.

This light, dry mulch worked perfectly. Since cattails are a water plant, there are no worries about it reseeding in the bed. The garden a couple months later. Because we had a warm and rainless February (usually our wettest month), our brassicas headed up rather than produced roots and only a few parsnips and carrots germinated. However our nitrogen-fixing favas and beans are great, our ‘mining’ potatoes are doing beautifully and the shallots are filling out well.

Every plant accumulates nutrition from the air and soil, and when that plant dies it delivers that nutrition to the topsoil. In the case of roots, when they die it is immediate hugelkultur. Without humans, plants drop leaves, fruit and seeds on the ground, where animals will nibble on them or haul them away but leave juice, shells and poo behind. When the plant dies, it dies in place and gives back to the topsoil. When we harvest from a plant we are removing that much nutrition from the soil. So when the plants are through producing, we cut the plants at the soil surface and leave the roots in the ground, and add the tops back to the soil. By burying kitchen scraps in vegetable beds you are adding back the sugars and other nutrients you’ve taken away with the harvest. It becomes a worm feast. Depending upon your climate and how warm your soil is, the scraps will take different lengths of time to decompose. Here in San Diego, a handful of food scraps buried in January is just about gone by February. No fertilizer needed!

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Using Pathways For Rain Catchment

Here in the drylands of San Diego we need to be especially sure to catch whatever rain may fall. Building good soil is vital for the entire planet because humans are going through decent topsoil like nobody’s business. Here at Finch Frolic Garden we’ve sheet mulched around trees to replicate decades of leaf drop, and on pathways to block weeds, prevent compaction and create good soil for shallow plant roots. We’ve also continued making our pathways work more for us by burying wood (hugelkultur) in the paths themselves. Most of our soil here is heavy clay, so creating drainage for roots is imperative. In sandy soils, creating more fungal activity to hold together the particles to retain water is important. We also need to store rain water when we get it, but not drown the roots of plants. This all can be accomplished by burying wood, the older the better.

Miranda and I have worked on many pathways, but for a few months this year the garden was given a huge boost forward with the help of Noel, a permaculture student and future farmer, who can move mountains in an afternoon with just a shovel.

The chosen pathways had these features: they were perpendicular to water flow, or were between trees that needed supplemental drainage, food and water access, and/or were where rainwater could be redirected. Eventually we’d like to do all the pathways like this but because of time, labor and materials we worked where it was most needed.

An area that becomes flooded when we have a deluge. The existing sheet mulch was pulled aside. Sections of the pathways were dug up (Noel’s work was very neat; my work is usually much less so). Wood was laid in the hole, and layered back with the dirt.

The pathway dug up and wood being layered. The nice, neat hole is Noel’s doing, not mine. Notice I said dirt, not soil. We don’t want to disturb good soil because we’d be killing microbes and destroying fungal networks. Dirt is another story; it needs amendment. As we’ve already buried all of our old wood, we timed these pathway ‘hugels’ to coincide with some appropriate tree removal.

You can be creative when cutting trees and make a chair! Watch out for sap on your pants, though. Trees were cut down and some climbing roses pruned back out of the pathway, and the green ‘waste’ was used in the nearby pathways.

This euphorbia was only sucking up water and not giving back anything, so it and its friends had to go. This one had a marking like an eye on it, and I was glad to see it go… as it was seeing me! Old palm fronds went in as well. No need to create additional work – good planning means stacking functions and saving labor.

The first layer of wood is covered with dirt, and then another layer added. After the wood was layered back with the dirt, the area was newly sheet mulched. Although the pathways are slightly higher, after another good rain (whenever that will happen) they’ll sink down and be level. They are certainly walkable and drivable as is. Although the wood is green, it isn’t in direct contact with plant roots so there won’t be a nitrogen exchange as it ages. When it does age it will become a sponge for rainwater and fantastic food for a huge section of the underground food chain, members of which create good soil which then feeds the surrounding plants. Tree roots will head towards these pantries under the paths for food. Rain overflow that normally puddles in these areas will penetrate the soil and soak in, even before the wood ages because of the air pockets around the organic material.

The best part about this, is that once it is done you don’t have to do it again in that place. Let the soil microbes take it from there. Every time you have extra wood or cuttings, dig a hole and bury it. You’ve just repurposed green waste, kept organics out of the landfill, activated your soil, fed your plants, gave an important purpose to the clearing of unwanted green material, and made your labor extremely valuable for years to come. Oh, and took a little exercise as well. Gardening and dancing are the two top exercises for keeping away dementia, so dig those hugels and then dance on them!

Burying wood and other organic materials (anything that breaks down into various components) is what nature does, only nature has a different time schedule than humans do. It takes sometimes hundreds of years for a fallen tree to decompose enough to create soil. That’s great because so many creatures need that decomposing wood. However for our purposes, and to help fix the unbelievable damage we’ve done to the earth by scraping away, poisoning and otherwise depleting the topsoil, burying wood hastens soil reparation for use in our timeline.

Another pathway is hard clay and isn’t on the top of my priority list to use for burying wood. However it does repel water due to compaction and because rainwater is so valuable I want to make this pathway work for me by catching rain. I’ve recommended to clients to turn their pathways into walkable (or even driveable) rain catchment areas by digging level-bottomed swales.

Digging gentle swales along a pathway can turn it into a rain catchment system. Make your paths work for you! A swale is a ditch with a level bottom to harvest water rather than channel water. However many pathways are on slopes or are uneven. So instead of trying to make the whole pathway a swale in an established garden, just look at the pathway and identify areas where the land has portions of level areas. Then dig slight swales in those pathways. Don’t dig deeply, you only have to gently shape the pathway into a concave shape with a level bottom. The swales don’t need to connect. You can cover the pathway and swales with bark mulch and they will still function for harvesting rain and still be walkable.

Mulching over the top makes the pathway even and still functional for rain catchment. If the pathways transect a very steep slope, you don’t want to harvest too much water on them so as not to undermine the integrity of your slope. This is a swale calculator if you have a large property on a steep slope.

So up-value your pathways by hugelkulturing them, and sheet-mulching on top. Whatever your soil, adding organics and mulching are the two best things to do to save water and build soil. And save the planet, so good going!