- Animals, Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Varmints

Year of the Gopher

They’ll eat tasty above-ground plants, too. This year should have been dubbed The Year of the Gopher. Every year brings an increase (and decrease) in some element in nature. There are big earwig years, painted bug years, cabbage moth years, just as there seem to be good and bad years for certain crops. This year seems to be a big one for gophers.

Pocket gophers are native to Southern California, and have their special roles to play in the landscape. They aerate, their tunnels are homes to lots of other animals and insects such as Pacific Chorus frogs, toads and lizards. They are food for snakes, raptors and even greater egrets. Their tunnels allow rainwater to penetrate the soil. And, like any of us, if offered really tasty specialty food they’ll go for it.

Cute little guy. Gopher tunnels are prime real estate. As explained in a past post, it takes a considerable amount of energy for gophers to dig tunnels, and if you kill them, new gophers reoccupy the tunnels from surrounding property. They are territorial and so the young are always looking for opportunities to have their own tunnel system.

Methods we’ve been using to train our gophers have been challenged this year by the desperation of our gophers, caused no doubt by the changing weather and growth patterns. In our kitchen garden we’ve lost a lot of veggies this spring.

We don’t trap and kill here, so we work with animals because this is their home and habitat. Permaculture isn’t about taking over an area to the loss of everything that usually lives there, its about working with nature and learning from it. So the reason our kitchen garden has been attacked is that we didn’t prepare well enough to live with the gophers. The only way to keep plants safe is to have boundaries around root balls. Trees we plant in gopher cages, but vegetables -not so much.

So Miranda and I decided to bury 24″ tall 1/4″ wire around the garden.

The north side oddly revealed no gopher tunnels. These tasks always sound so easy! Trenching through clay in the heat of early summer has been a challenge. Gopher tunnels dug for food collection are within the first 18″ of dirt, and their nests are down to about 24″.

Gopher nesting material about nine inches under the ground. This is in such hard dirt that I have to use a pick on it. We pulled back sheet mulch on the pathways and found incredible fungal activity, loads of worms and moisture.

Peeling back sheet mulch that was only six months old showed lots of fungal activity already.

Newspaper being consumed by fungus and turned into soil.

A great lump of fungal hyphae, if I may say so myself. While trenching we found gopher tunnels into the garden, and often would find dirt in the trench under the holes as the gopher backfilled, trying to make a new dirt tunnel across the channel.

The east side we thought would be the most difficult, with the dirt rock-hard at the corner. We thought that until we began the fourth trench. Yikes! Along one active area I buried the wire, but also wanted to retard the invasion of Bermuda grass. Along with the wire I buried a couple of pieces of scrap 3/4″ plywood to make a physical boundry for the grass, and these happen to be right where a gopher tunnel was. The next morning I was in the garden and I heard a strange thumping sound, and finally realized that it was coming from underground where the wood was buried. The gopher was trying to get through the new wooden fence and wire!

We’ve buried wire around three sides (40′ long by 20 – 24″ deep), and are slaving away at the last trench where the most gopher activity is.

Burying the wire, shoving some rotten fruit into the gopher tunnel entrances and refilling. As we’re working, we’re also using a spade to collapse gopher tunnels from the back out, and using the smucky water (this batch is made from onion peels and bits leftover from pickling whole onions) to ruin those tunnels. We’re herding the gopher out of the garden and fertilizing at the same time.

We’ve a couple more bouts left to go before finishing; my partially numb hands are ready to be done with it. Narrow trenches in heavy clay right next to a fence aren’t easy to work in, which slows the process down a lot. Knowing that we’re being true to what we believe in, to not trap and kill in our garden, makes it all worth the work. The gopher is welcome to all the weed roots it wants elsewhere.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Predators, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving

Polyculture In A Veggie Bed

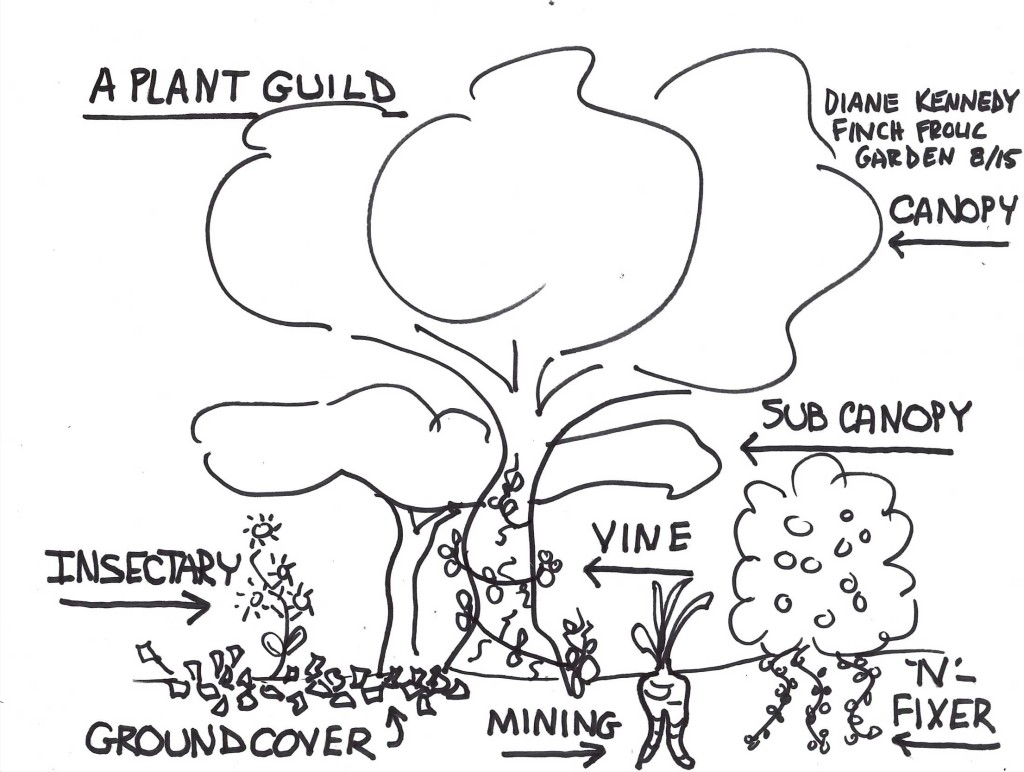

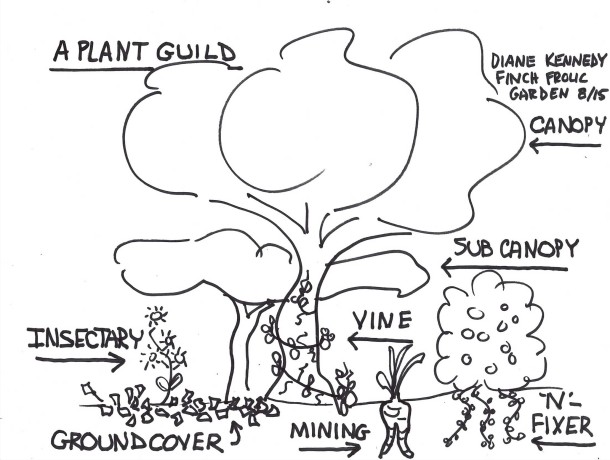

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

By burying sticks in planting holes you are helping feed the soil and hold water. When planting veggies here at Finch Frolic Garden I often mix up a handful of vegetable, herb and flower seeds that fulfill the plant guild guidelines and plant them all in one area. They come up in a mix of heights, colors, shapes and scents to fool bugs. The result is like a miniature forest.

A merry mixture of vegetables, herbs and flowers in a mature bed. However that sort of wild designed planting has its drawbacks. Harvesting is more time consuming (although more fun, like a treasure-hunt). Many people find peace in looking at rows of vegetables, and peace is valuable.

We disturb the soil as little as possible, and pull the soil back for potatoes. You can plant polyculture in rows as well. Just plant each row with a different member of the plant guild, and you’ll achieve a similar effect with insect confusion, and with nutrient conservation.

In this small, slightly sunken bed (we are in drylands so we plant concave to catch water), we planted rows of three kinds of potatoes, two kinds of shallots, a row each of bush beans, fava beans, parsnips, radish and carrots.

Miranda planting potatoes and shallots before the smaller seeds go in. We covered the bed with a light mulch made from dried dwarf cattail stems. This sat lightly on the soil and yet allowed light and water penetration, giving the seedlings protection from birds and larger bugs.

This light, dry mulch worked perfectly. Since cattails are a water plant, there are no worries about it reseeding in the bed. The garden a couple months later. Because we had a warm and rainless February (usually our wettest month), our brassicas headed up rather than produced roots and only a few parsnips and carrots germinated. However our nitrogen-fixing favas and beans are great, our ‘mining’ potatoes are doing beautifully and the shallots are filling out well.

Every plant accumulates nutrition from the air and soil, and when that plant dies it delivers that nutrition to the topsoil. In the case of roots, when they die it is immediate hugelkultur. Without humans, plants drop leaves, fruit and seeds on the ground, where animals will nibble on them or haul them away but leave juice, shells and poo behind. When the plant dies, it dies in place and gives back to the topsoil. When we harvest from a plant we are removing that much nutrition from the soil. So when the plants are through producing, we cut the plants at the soil surface and leave the roots in the ground, and add the tops back to the soil. By burying kitchen scraps in vegetable beds you are adding back the sugars and other nutrients you’ve taken away with the harvest. It becomes a worm feast. Depending upon your climate and how warm your soil is, the scraps will take different lengths of time to decompose. Here in San Diego, a handful of food scraps buried in January is just about gone by February. No fertilizer needed!

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Using Pathways For Rain Catchment

Here in the drylands of San Diego we need to be especially sure to catch whatever rain may fall. Building good soil is vital for the entire planet because humans are going through decent topsoil like nobody’s business. Here at Finch Frolic Garden we’ve sheet mulched around trees to replicate decades of leaf drop, and on pathways to block weeds, prevent compaction and create good soil for shallow plant roots. We’ve also continued making our pathways work more for us by burying wood (hugelkultur) in the paths themselves. Most of our soil here is heavy clay, so creating drainage for roots is imperative. In sandy soils, creating more fungal activity to hold together the particles to retain water is important. We also need to store rain water when we get it, but not drown the roots of plants. This all can be accomplished by burying wood, the older the better.

Miranda and I have worked on many pathways, but for a few months this year the garden was given a huge boost forward with the help of Noel, a permaculture student and future farmer, who can move mountains in an afternoon with just a shovel.

The chosen pathways had these features: they were perpendicular to water flow, or were between trees that needed supplemental drainage, food and water access, and/or were where rainwater could be redirected. Eventually we’d like to do all the pathways like this but because of time, labor and materials we worked where it was most needed.

An area that becomes flooded when we have a deluge. The existing sheet mulch was pulled aside. Sections of the pathways were dug up (Noel’s work was very neat; my work is usually much less so). Wood was laid in the hole, and layered back with the dirt.

The pathway dug up and wood being layered. The nice, neat hole is Noel’s doing, not mine. Notice I said dirt, not soil. We don’t want to disturb good soil because we’d be killing microbes and destroying fungal networks. Dirt is another story; it needs amendment. As we’ve already buried all of our old wood, we timed these pathway ‘hugels’ to coincide with some appropriate tree removal.

You can be creative when cutting trees and make a chair! Watch out for sap on your pants, though. Trees were cut down and some climbing roses pruned back out of the pathway, and the green ‘waste’ was used in the nearby pathways.

This euphorbia was only sucking up water and not giving back anything, so it and its friends had to go. This one had a marking like an eye on it, and I was glad to see it go… as it was seeing me! Old palm fronds went in as well. No need to create additional work – good planning means stacking functions and saving labor.

The first layer of wood is covered with dirt, and then another layer added. After the wood was layered back with the dirt, the area was newly sheet mulched. Although the pathways are slightly higher, after another good rain (whenever that will happen) they’ll sink down and be level. They are certainly walkable and drivable as is. Although the wood is green, it isn’t in direct contact with plant roots so there won’t be a nitrogen exchange as it ages. When it does age it will become a sponge for rainwater and fantastic food for a huge section of the underground food chain, members of which create good soil which then feeds the surrounding plants. Tree roots will head towards these pantries under the paths for food. Rain overflow that normally puddles in these areas will penetrate the soil and soak in, even before the wood ages because of the air pockets around the organic material.

The best part about this, is that once it is done you don’t have to do it again in that place. Let the soil microbes take it from there. Every time you have extra wood or cuttings, dig a hole and bury it. You’ve just repurposed green waste, kept organics out of the landfill, activated your soil, fed your plants, gave an important purpose to the clearing of unwanted green material, and made your labor extremely valuable for years to come. Oh, and took a little exercise as well. Gardening and dancing are the two top exercises for keeping away dementia, so dig those hugels and then dance on them!

Burying wood and other organic materials (anything that breaks down into various components) is what nature does, only nature has a different time schedule than humans do. It takes sometimes hundreds of years for a fallen tree to decompose enough to create soil. That’s great because so many creatures need that decomposing wood. However for our purposes, and to help fix the unbelievable damage we’ve done to the earth by scraping away, poisoning and otherwise depleting the topsoil, burying wood hastens soil reparation for use in our timeline.

Another pathway is hard clay and isn’t on the top of my priority list to use for burying wood. However it does repel water due to compaction and because rainwater is so valuable I want to make this pathway work for me by catching rain. I’ve recommended to clients to turn their pathways into walkable (or even driveable) rain catchment areas by digging level-bottomed swales.

Digging gentle swales along a pathway can turn it into a rain catchment system. Make your paths work for you! A swale is a ditch with a level bottom to harvest water rather than channel water. However many pathways are on slopes or are uneven. So instead of trying to make the whole pathway a swale in an established garden, just look at the pathway and identify areas where the land has portions of level areas. Then dig slight swales in those pathways. Don’t dig deeply, you only have to gently shape the pathway into a concave shape with a level bottom. The swales don’t need to connect. You can cover the pathway and swales with bark mulch and they will still function for harvesting rain and still be walkable.

Mulching over the top makes the pathway even and still functional for rain catchment. If the pathways transect a very steep slope, you don’t want to harvest too much water on them so as not to undermine the integrity of your slope. This is a swale calculator if you have a large property on a steep slope.

So up-value your pathways by hugelkulturing them, and sheet-mulching on top. Whatever your soil, adding organics and mulching are the two best things to do to save water and build soil. And save the planet, so good going!

- Animals, Bees, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.Plant the appropriate plants for where you are placing them, for your soil and water use, and stack them in a guild with compatible plants that you can use. The ground will be covered by a foliar density that will keep grasses and other weeds at bay and provide excellent habitat for a full range of animals and insects. By stacking plants in a guild you are bringing life and abundance back to your garden.

Does it still sound so complicated? Rather than try to learn the roles of all the plants in the world, start small. Make a list of all the plants you want to plant. List them under food bearing, culinary/medicinal herb, craft/building material, and ornamental. Then read up on those plants. What size are they at maturity? Do they need full sun, partial or full shade? If trees, do they have an upright growth so you may plant under them (stonefruit), or do they like to have their roots covered and don’t like plants directly under them (citrus and avocado)?

Citrus doesn’t like plants under its canopy, but does like plants outside its dripline. Are they annuals, perennials or biennials? What is their growth habit: sprawling, rooting where they spread, upright bushy, do they need support and can they cling or do they need to be tied to a support?

Will the plant twine on its own? Do they require digging up to harvest? Do they fix nitrogen in the soil? Do they drop leaves or are they evergreen? Are they fragrant? When are their bloom times? Fruiting times? Are they cold tolerant or do they need chill hours? How much water do they need? What are their companion plants (there are many guides for this online, or in books on companion planting.)

Do vines or canes need to be tied to supports? As you are acquainting yourself with your plants, you can add to their categorization, and shift them into the parts of a plant guild. Yes, many plants will be under more than one category… great! Fit them into the template under only one category, because diversity in the guild is very important.

Draw your guilds with their plants identified out on paper before you begin to purchase plants. Decide where the best location for each is on your property. Tropical plants that are thirsty and don’t have cold tolerance should go in well-draining areas towards the top or middle of your property where they can be easily watered. Plants that need or can tolerate a chill should go where the cold will settle.

Once it is on paper, then start planting. You don’t have to plant all the guilds at once… do it as you have time and money for it. Trees should come first. Bury wood to nutrify the soil in your beds, and don’t forget to sheet mulch.

Remember that in permaculture, a garden is 99% design and 1% labor. If you think buying the plants first and getting them in the ground without planning is going to save you time and money, think again. You are gambling, and will be disappointed.

Have fun with your plant guilds, and see how miraculous these combinations of plants work. When you go hiking, look at how undisturbed native plants grow and try to identify their components in nature’s plant guild. Guilds are really the only way to grow without chemicals, inexpensively and in a way that builds soil and habitat.

You can find the rest of the 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries .

- Animals, Birding, Building and Landscaping, Chickens, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Houses, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Podcasts with Diane Kennedy

Two podcasts with me talking about permaculture, Finch Frolic Garden, and how you can save money and the world through gardening! 🙂 Please let me know what you think:

This is a podcast with Sheri Menelli of earthfriendlyhomeowner.com, where I talk pretty much without a pause for breath for about the first ten minutes. Recorded in May, 2015.

http://www.earthfriendlyhomeowner.com/ep7-interview-with-diane-kennedy-of-finch-frolic-gardens-and-vegetariat-com/

This is a podcast with Greg Peterson of Urban Farm Podcasts, released Jan. 7, 2016, and you can listen to it several ways:

Urban Farm U:

http://www.urbanfarm.org/category/podcast/

iTunes:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/urban-farm-podcast-greg-peterson/id1056838077?mt=2

You can sign up for free to hear all their great podcasts here.

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Natives, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants

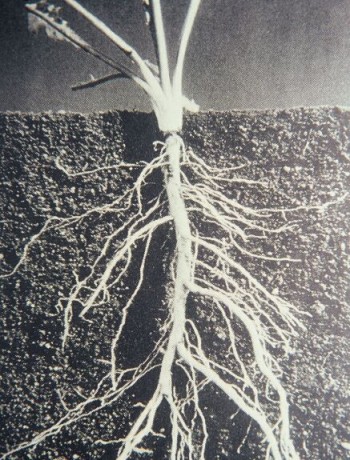

The beauteous taproot. In the last post we explored one way plants take nitrogen out of the air and fix it in the soil. Now we’ll explore how plants take nutrients from deep in the soil and deliver them to the soil surface. This is another way that plants create high nutrient topsoil.

All rooted plants gather nutrition from the soil, store it in their leaves, flowers and fruit, and then create topsoil as these products fall to the ground. Every plant is a vitamin pill for the soil. When you pull ‘weeds’, clear your garden, prune and otherwise amass greenery and deadwood, you are gathering vitamins and minerals for your soil. Bury it. All of it. If its too big to bury, then chip it and use it as top mulch. Allow that nutrition to return to the soil from whence it came. No stick or leaf should leave your property! Period.

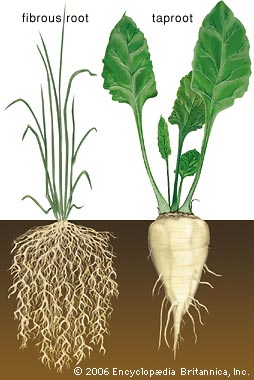

Fiberous roots hold soils together, and taproots dig. There are mainly two kinds of root systems: fibrous (like many grasses) and taprooted. Some taprooted plants grow very deeply. Those plants that are deemed ‘mining’ plants go the extra mile. I envision mining plants as the gruff gentlemen of the plant guild: tough and weathered, dressed in pith helmet and explorer clothes with a larger-than life character and a heart of gold.

A monument to Sir Henry Morton Stanley. I don’t know if he had a heart of gold or was gruff. Okay, too many old movies on my part. The roots of mining plants are large taproots that explore the depth of the soil searching for deep water. Depending upon the size of the plant, these roots can break through hardpan and heavy soils. They create oxygen and nutrient channels, digging tunnels that weaker roots from less bold plants and soft-bodied soil creatures can follow. When these large roots die they decompose deep in the ground, bringing that all-important organic material into the soil to feed microbes. Meanwhile these Indiana Jones’s of the root world are finding pockets of minerals deep in the soil – far below the topsoil and where other roots can’t reach – and are taking them into their bodies and up into their leaves. When these leaves die off and fall to the ground they are a super rich addition to the topsoil. Often the deep taprooted plants have a sharp scent or taste. Many weeds found in heavy soils are mining plants, sent by Mother Nature to break up the dirt and create topsoil. Dicotyledonous (dicot) plants have deep taproots, if you are into that kind of thing. The benefits of a plant having a deep taproot is not only to search for deep water, but to store a lot more sugar in the root, be anchored firmly, and to withstand drought better.

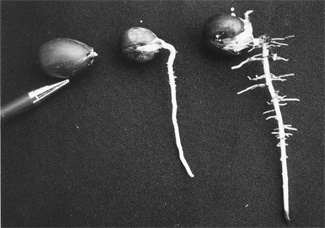

So who are these helpful gentlemen adventurers of the plant guilds? Comfrey and artichoke are two commonly used mining plants. Also members of the, radish, mustard, and carrot family such as, parsnip, root celery, horseradish, burdock, parsley, dandelion, turnip, and poppy to name a few. There is also milkweed (Asclepias), coneflower, chicory, licorice, pigeon pea, and for California natives there is sagebrush, Matilija poppy, oaks, mesquite, Palo Verde and many more. Most deep taprooted plants don’t transplant well because their straight taproot is often much longer than the top of the plant. Check out a sprouted acorn. The taproot is many times as deep as the top is high.

Three day’s difference in germinating acorns. Talk about taproot! Image from www.landscapeonline.com. Yet some mining plants such as comfrey and horseradish can be divided or will sprout from pieces of the root left in the ground. Deep taprooted weeds seem to all be like that, at least on my property!

Horseradish: the root is edible and medicinal, and the leaves are a spicy treat!

Grating horseradish for sauce, and still tearing up! Now for a little comfrey prosthelytizing: Comfrey keeps coming back when chopped, so it is often grown around fruit producing trees to be chopped and dropped as a main fertilizer. Its leaves are so high in nutrition that they are a compost activator, an excellent hen and livestock food (dried it has 26% protein), and have been heavily used in traditional medicine. Also called Knitbone, the roots contain allantoin, a substance also found in mother’s milk, which among other benefits helps heal bone breaks when applied topically.

A handsome comfrey plant working in the garden. The plant also has flowers that bees and other insects love. It spreads by seeds as well as divisions, and non-permaculture gardeners don’t like it escaping in their gardens. I only wish that mine would spread faster, to create more fertilizer. Comfrey grows the best greens with some irrigation and better soil, so it is perfect for use around fruit trees.

So when planting a guild you can easily plant miners that are edible. If you harvest those deep taproots, such as carrots or parsnips, then be sure to trim the greens and let them fall on the spot, so the plant will have done its full duty to the soil. Unless the plant can take division, such as the aforementioned comfrey, then planting seeds are best. Deep taprooted plants in pots are often stunted and either don’t survive transplanting well, or will take a long time to grow on top because they need to grow so much on the bottom first.

Next up: the exciting groundcover plants!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy!

The many layers of a food forest, Finch Frolic Garden. Yours doesn’t have to be this rampant and wild; your plant guilds can look perfectly proportioned and decorative and still be permaculture. The next part of this scintillating series of What Is A Plant Guild focuses on sub-canopy, or the understory. Sub-canopy does many of the same things that upper canopy does, in a more intensive way.

Smaller trees are ‘nurseried’ in with the help of faster-growing canopy trees; in other words, the upper canopy helps shade and protect the sub-canopy from scorching sun, high winds, pounding hard rain and hail, etc. However, sub-canopy trees can also be made of the slower, longer-lived canopy trees that will eventually dominate the plant guild/forest. You can try these guys for tree falling. I’ve talked about how, if an area of forest was wiped clear and roped off, in a hundred years the beginnings of a hardwood forest will have begun. This is due to succession plants making the soil ready for the next. Each plant has a purpose. This phrase is an essential mantra in permaculture because it lets you understand what the plants are doing and then you can let them do it. So if you planted a fast-growing soft wood canopy tree, maybe even one that is a nitrogen-fixer, such as ice cream bean, or acacia, with a sub-canopy trees that include both something that is going to stay relatively small such as a semi-dwarf fruit tree, along with a slower growing, hardwood tree such as an oak which will eventually become the true canopy tree years down the line, then the original softwood tree would eventually be sacrificed and used as mulch and hugelkultur after the hardwood tree had gained enough height. Wow, that was a long sentence. At first that hardwood tree would be part of the sub-canopy until it grows up. Meanwhile there are other true sub-canopy trees that stay in that height zone for their life.

What makes up a plant guild. Remember, too, that plant guilds are relative in size. If you have a small backyard you may not have room for a tall canopy tree, especially if it is detrimental to the rest of the property. So scale the whole guild down. Canopy for you could be a dwarf fruit tree, and sub-canopy could be blueberry bushes. In a vegetable setting the canopy could be corn or Jerusalem artichokes, where you either leave the dead canes up overwinter (a great idea to help the birds), or chop and drop them to protect the soil, which mimics the heavy leaf drop from a deciduous tree. The plant guild template is the same; the dimensions change with your needs and circumstance. Get more details on how to take good care of the trees with the help of experts.

So sub-canopy buffers sunlight coming in from an angle.

It receives rain from the upper canopy further slowing it down and shattering the droplets so that it doesn’t pound the earth. The lower branches also help catch more fog, allowing it to precipitate and drip down as irrigation. Leaves act as drip irrigation, gathering ambient moisture, condensing it, helping clean it, and dripping it down around the ‘drip line’ of the trees, just where the tree needs it.

An oak working a temp job as sub-canopy until it grows into canopy, being a support for climbing roses and nitrogen-fixing wisteria. This is the formal entrance to Finch Frolic Garden. With its sheltering canopy it holds humidity closer to the ground. In the previous post I talked about the importance of humidity in dry climates for keeping pollen hydrated and viable.

It further helps calm and cool winds, and buffers frost and snow damage. Sub-canopy gives a wide variety of animals the conditions for habitat: food, water, shelter and a place to breed. While the larger birds, mostly raptors, occupy the upper canopy, the mid-sized birds occupy the sub-canopy. Depending upon where you live, a whole host of other animals live here too: monkeys, big snakes, leopards, a whole host of butterflies and other insects using the leaves as food and to form chrysalis, tree squirrels, etc. Although many of these also can use canopy, it is the sub-canopy that provides better shelter, better materials for nesting, and most of the food supply. And again, the more animals, the more organic materials (poop, fur, feathers, dinner remains) will fall to fertilize the soil.

Sub-canopy gives us humans a lot of food as well, for in a backyard plant guild this can be the smaller fruit trees and bushes.

Sub-canopy also provides more vertical space for vines to grow. More vines mean more food supply that is off the ground. A famous example of companion planting is the ‘three sisters’ Native American method… what tribe and where I’m not sure of… where corn is planted with climbing beans and vining squash. The corn, as mentioned before, is the canopy, the beans use the corn as vertical space while also fixing nitrogen in the soil (we’ll discuss nitrogen fixers in another post), and the squash is a groundcover (also will be covered in another post). There is more to the three sisters than you think. Raccoons can take down a corn crop in a night; however, they don’t like to walk where they can’t see the ground, i.e. heavy vines, so the squash acts as a raccoon deterrent. To stray even further off-topic, there is also a fourth sister which isn’t talked about much, and that is a plant that will attract insects.

Back to sub-canopy, while some of it can be long term food production trees or plants, it too can also have shorter chop-and-drop trees. Chop-and-drop is a rather violent term given to the process of growing your own fertilizer. Most of these trees and plants are also nitrogen fixers. These fast-growing plants are regularly cut, and here is where the difference between pruning and chopping comes to bear, because you aren’t shaping and coddling these trees with pruning, you are quickly harvesting their soft branches and leaves to drop on the ground around your plant guild as mulch and long term fertilizer. If these trees are also nitrogen fixers, then when you severely prune them the nitrogen nodules on the roots will be released in the soil as those roots die; the tree will adjust the extent of its roots to the size of its canopy because with less canopy it cannot provide enough nutrients for that many roots, and it doesn’t need that many roots to provide food for a smaller canopy. Wow, another huge sentence. In this system you are growing your own fertilizer, which is quickly harvested maybe only a couple of times a year. Chemical-free. So, by planting sub-canopy that is long term food producing trees such as apricots or apples, along with smaller trees and shrubs that are also sub-canopy but are sacrificial to be used as fertilizer such as senna or acacia or whatever grows well in your region, you have the most active and productive part of your plant guild.

Sub-canopy, therefore, provides shelter for hardwoods, provides a lot of food for humans as well as habitat for so many animals, it provides fertilizer both because of its natural leaf drop and because of those same animals living in it, but also as materials for chopping and dropping, it buffers sun, wind and rain, holds humidity, offers vertical space for food producing vines which will then be in reach for easier harvesting, and much more that I haven’t even observed yet but maybe you already have.

The next part of the series will focus on nitrogen-fixers! Stay tuned. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guilds #2: Upper Canopy

An oak is home to over 300 species. Not counting human. Whether you are planting small plants in pots, ornamentals in your yard or a food forest, you need plants that will provide an upper canopy for others. If you have small plants, then you will have a short canopy. Maybe your canopy is a tomato plant. Maybe its an oak. Whatever it is, canopy has many functions.

Upper canopy provides shade so that other plants can grow. It drops leaves, bark, flowers and seeds and/or fruit to provide compost and food for all levels of animals down to soil microbes. Canopy provides protective shelter for many kinds of mammals, birds, reptiles and insects as they hide under the leaves. A mature oak is home to over 300 species. Old scarred canopy full of holes is the natural home for honeybees, and many types of bird and other animal. It is a storage unit for acorns gathered by woodpeckers. Where you have animals, you have droppings. All the poo, feathers, regurgitated pellets, fur, scales and other organic waste that falls from canopy is vitally important for the health of the soil below.

Canopy provides a perch for raptors and larger birds that help with rodent control.

Canopy helps slow the wind; the fewer trees we have the harder the winds. Canopy also filters the wind, blocking dust and other debris. Canopy helps cool and moisturize the wind. The leaves of canopy trees help buffer the rain. Rain on bare ground is as compacting as driving over the dirt with a tractor. If rain hits leaves it bounces, rolls or shatters. Rain can then hit other layers below the canopy, finally rolling through leaf mulch to percolate into the soil without compacting it.

Canopy catches moisture as well. Here in Southern California we may not receive a lot of rain, but we do have moisture during the night.

Often I’ve walked through Finch Frolic Garden of a morning to feed the hens, and the garden sounded as if it had its own special rain cloud over it. That is because moisture condenses on the leaves and rolls off. The more canopy and the higher the canopy, the more water we can collect. In that same way, canopy begins to hold humidity on the property, which the rest of the guild contributes to. Pollen dries out. With longer, hotter, drier summers there is worse pollination even if the pollinators are active, because the pollen isn’t viable. Less humidity equals fewer fruits, nuts and vegetables. Therefore, the more canopy, and other parts of a guild, the moister the air and the better the harvest.

Often I’ve walked through Finch Frolic Garden of a morning to feed the hens, and the garden sounded as if it had its own special rain cloud over it. That is because moisture condenses on the leaves and rolls off. The more canopy and the higher the canopy, the more water we can collect. In that same way, canopy begins to hold humidity on the property, which the rest of the guild contributes to. Pollen dries out. With longer, hotter, drier summers there is worse pollination even if the pollinators are active, because the pollen isn’t viable. Less humidity equals fewer fruits, nuts and vegetables. Therefore, the more canopy, and other parts of a guild, the moister the air and the better the harvest.

Canopy is in connection with all other plants in its community, linked via webs called mycorrhizal fungi. Through these webs the canopy sends chemical messages and nutrients to other plants. Every plant in the community benefits from the strong communications from the canopy trees.

Canopy builds soil. Canopy trees are large on top and equally large underground. Tree root growth can mirror the height and width of the above-ground part, and it can be larger. Therefore canopy trees and plants break through hard soil with their roots, opening oxygen, nutrient and moisture pathways that allow the roots of other plants passage, as well as for worms and other decomposers. As the roots die they become organic material deep in the soil – effortless hugelkultur; canopy is composting above and below the ground. Plants produce exudates through their roots – sugars, proteins and carbohydrates that attract and feed microbes. Plants change their exudates to attract and repel specific microbes, which make available different nutrients for the plant to take up. A soil sample taken in the same spot within a month’s time may be different due to the plant manipulating the microbes with exudates. Not only are these sticky substances organic materials that improve the soil, but they also help to bind loose soil together, repairing sandy soils or those of decomposed granite. The taller the canopy, the deeper and more extensive are the roots working to build break open or pull together dirt, add nutrients, feed and manage microbes, open oxygen and water channels, provide access for worms and other creatures that love to live near roots.

Canopy roots have different needs and therefore behave differently depending upon the species. Riparian plants search for water. If you have a standing water issue on your property, plant thirsty plants such as willow, fig, sycamore, elderberry or cottonwood. In nature, riparian trees help hold the rain in place, storing it in their massive trunks, blocking the current to slow flooding and erosion, spreading the water out across fields to slowly percolate into the ground, and turning the water into humidity through transpiration. The roots of thirsty plants are often invasive, so be sure they aren’t near structures, water lines, wells, septic systems or hardscape. Some canopy trees can’t survive with a lot of water, so the roots of those species won’t be destructive; they will flourish in dry and/or well-draining areas building soil and allowing water to collect underground.

In large agricultural tracts such as the Midwest and California’s Central Valley, the land is dropping dramatically as the aquifers are pumped dry. Right now in California the drop is about 2 inches a month. If the soil is sandy, it will again be able to hold rainwater, but without organic materials in the soil to keep it there the water will quickly flow away. If the soil is clay, those spaces that collapse are gone and no longer will act as aquifers… unless canopy trees are grown and allowed to age. Their root systems will again open up the ground and allow the soil to be receptive to water storage. Again, roots produce exudates, and roots swell up and die underground leaving wonderful food for beneficial fungi, microbes, worms and all those soil builders. The solution is the same for both clay and sandy soils – any soil, for that matter. Organic material needs to be established deep underground, and how best to do that than by growing trees?

In permaculture design, the largest canopy is often found in Zone 5, which is the native strip. In Zone 5 you can study what canopy provides, and use that information in the design of your garden.

How do you achieve canopy in your garden? If your canopy is something that grows slowly, then you will need to nursery it in with a fast-growing, shorter-lived tree that can be cut and used as mulch when the desired canopy tree becomes well established. Some trees need to be sacrificial to insure the success of your target trees. For instance, we have a flame tree that was part of the original plantings of the garden. It is being shaded out by other trees and plants, and all things considered it doesn’t do enough for the garden to be occupying that space (everything in your garden should have at least three purposes). However a loquat seeded itself behind the flame tree, and the flame tree helped nursery it in. We love loquats, so the flame tree may come down and become buried mulch (hugelkultur), allowing that sunlight and nutrient load to become available for the loquat which is showing signs of stress due to lack of light. With our hotter, drier, longer summers, many fruit trees need canopy and nurse trees to help filter that intense heat and scorching sunlight. Plan your garden with canopy as the mainstay of your guild.

How do you achieve canopy in your garden? If your canopy is something that grows slowly, then you will need to nursery it in with a fast-growing, shorter-lived tree that can be cut and used as mulch when the desired canopy tree becomes well established. Some trees need to be sacrificial to insure the success of your target trees. For instance, we have a flame tree that was part of the original plantings of the garden. It is being shaded out by other trees and plants, and all things considered it doesn’t do enough for the garden to be occupying that space (everything in your garden should have at least three purposes). However a loquat seeded itself behind the flame tree, and the flame tree helped nursery it in. We love loquats, so the flame tree may come down and become buried mulch (hugelkultur), allowing that sunlight and nutrient load to become available for the loquat which is showing signs of stress due to lack of light. With our hotter, drier, longer summers, many fruit trees need canopy and nurse trees to help filter that intense heat and scorching sunlight. Plan your garden with canopy as the mainstay of your guild.Therefore a canopy plant isn’t in stasis. It is working above and below ground constantly repairing and improving. By planting canopy – especially canopy that is native to your area – you are installing a worker that is improving the earth, the air, the water, the diversity of wildlife and the success of your harvest.

What makes up a plant guild. Canopy is improving the water storage of the soil and increasing potential for aquifers. The more site-appropriate, native canopy we can provide in Zone 5, and the more useful a canopy tree as the center of a food guild, the better off everything is. All canopy asks for in payment is mulch to get it started.

Next week we’ll explore sub-canopy! Stay tuned! You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Dessert, Fruit, Gardening adventures, Herbs, Special Events, Spices, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian, Water Saving

Our Annual Marketplace, and Last Tours of 2015

Our fourth-annual Finch Frolic Marketplace will take place Nov. 21 and 22nd from 9 – 2. We’ve been working like little permaculture elves, harvesting, preparing fruit and vegetables, canning, baking, and inventing new recipes for your table and for gifts. We have a curry spice mixture that is amazing. Our record white guava harvest has allowed us to create sweet guava paste and incredible guava syrup. We’ve pickled our garlic cloves, as well as zucchino rampicante, and our Yucatan Pickled Onions have a wonderful orange and oregano base that is fabulous. Of course there is Miranda’s small-batch Pomegranate Gelato, Whiskey-Baked Cranberry Relish, and a selection of curds (passionfruit, lemon-lime, and cranberry). So much more, too. We’ll also be selling plants from several sources, and some collectibles and knick-knacks from my home. Please come support a small business early – a whole week before Small Business Saturday! Your patronage allows us to continue teaching permaculture.

Our fourth-annual Finch Frolic Marketplace will take place Nov. 21 and 22nd from 9 – 2. We’ve been working like little permaculture elves, harvesting, preparing fruit and vegetables, canning, baking, and inventing new recipes for your table and for gifts. We have a curry spice mixture that is amazing. Our record white guava harvest has allowed us to create sweet guava paste and incredible guava syrup. We’ve pickled our garlic cloves, as well as zucchino rampicante, and our Yucatan Pickled Onions have a wonderful orange and oregano base that is fabulous. Of course there is Miranda’s small-batch Pomegranate Gelato, Whiskey-Baked Cranberry Relish, and a selection of curds (passionfruit, lemon-lime, and cranberry). So much more, too. We’ll also be selling plants from several sources, and some collectibles and knick-knacks from my home. Please come support a small business early – a whole week before Small Business Saturday! Your patronage allows us to continue teaching permaculture.

Join us for a tour! Our last two Open Tours will also be held that weekend, each at 10 am. The tours last about two hours and we should be having terrific weather for you to enjoy learning basic permaculture as we stroll through the food forest. Please RSVP for the tours to dianeckennedy@prodigy.net. More about the tours can be found under the ‘tours’ page on this blog.

Finch Frolic Garden will be closing for the winter, from Thanksgiving through March 1. However, Miranda and I will still be available for consultations, designs, lectures and workshops, and we will be adding posts to Vegetariat and Finch Frolic Facebook (you don’t need to be a member of Facebook to view our page!).

Have a very safe and very happy holiday season. Care for your soil as you would your good friends and close family, with swales, sheet mulch and compost, and it will care for you for years.

Diane and Miranda

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Living structures, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Photos, Ponds, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

October Garden

A huge dragonfruit; this kind is white inside. October is one of my favorite months, even when we’re on fire here in Southern California. This year we’ve been saved, and October is moderate in temperature and lovely.

A volunteer kabocha squash vining its way through a bush.

Our first ripeing macadamia harvest from a 3 year old tree, with a dragonfriuit snaking through.

Edible hibiscus, volunteer nasturtiums and pathway across the rain catchment basin.

Into the wisteria-covered Nest. Summer has lost her vicious grip and we have time until the holiday rush and winter cold. Finch Frolic Garden has withstood the heat, the dry, the inundations, the snow and the changes, all without chemicals or much human intervention.

Grasshopper freshly out of last instar.

The curly willow trellis. We’ve lost some trees and shrubs this year, but that is mostly due to the faulty irrigation system which delivers too much or too little, and is out of sight underground.

Urbanite pathway.

Bulbs will pop up year round for wonderful surprises. Permaculture methods in sheet mulching, plant guilds, swales, rain catchment basins, and the use of canopy have pulled this garden through.

Loquat in bloom.

Bridge over currently dry streambed.

Bamboo bridge.

A gourd in a liquidamber. The birds, butterflies and other insects and reptiles are out in full force enjoying a safety zone. A few days ago on an overcast morning, Miranda identified birds that were around us: nuthatches, crows, song sparrows, a Lincoln sparrow, spotted towhees, California towhees, a kingfisher, a pair of mallards, a raven, white crowned sparrows, a thrush, lesser goldfinches, house finches, waxwings, robin, scrub jays, mockingbird, house wren, yellow rumped warbler, ruby crowned kinglet, and more that I can’t remember or didn’t see.

Squash!

This birch has strange red fruit in its top boughs…

…a volunteer cherry tomato that is fruiting inconveniently ten feet up. Birds have identified our property as a migratory safe zone. No poisons, no traps. Clean chemical-free pond water to drink. Safety.

Squash and gourds happily growing out of the hugelkultur mound.

A surprise pumpkin hiding in the foliage.

A huge and lovely gourd.

Vines taking advantage of vertical spaces by going up the trees. You can provide this, too, even in just a portion of your property. The permaculture Zone 5.

Why did the gourd cross the road? To climb up a liquidamber, apparently.

A glimpse of pond through the withy hide

Mouse melons on a tiny vine. More cucumber than melon, they grow to be olive-sized.

Time for me to get in the water and trim back the waterlilies before the water temperature drops!

Purple water lilies in the pond. I’m indulging in showing you photos from that overcast October morning, and I hope that you enjoy them.

Eden rose never fails.

Sweet potato vines escaping the veggie garden; the leaves are edible.

See the long tan thing on the trunk? That’s a zucchino rampicante, an Italian zucchini. Eat it green, or leave it to become a huge winter squash.

Violetta artichokes regrowing in our veggie garden, with a late eggplant coming up through sweet potato vines.