Vegetables

- Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian

Watermelon Radish

It looks a little like an alien species! We’ve planted a lot of new varieties this year. Still there are seed packages left unopened! So much fun, though. One veggie that we bought from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds is a beautiful radish called Chinese Red Meat Radish, or Watermelon Radish.

The green/white/pink outer color on the swollen roots is a little disconcerting. I’m not a huge fan of radishes. They grow quickly, help identify rows of slower-growing seeds, and are great for kids to plant. Still neither me nor my tummy really likes the strong radish flavor.

Slicing into them is a little creepy. The Watermelon Radish, however, are large, crisp and sweet on the inside. My daughter cut them into small triangles and stir-fried them. They had a little of the bitter radish flavor, but if you expect that you will be delighted at the taste and color.

These brilliant little wedges don’t hold much heat and are great raw, in stir-fries, or lightly cooked on their own. Younger ones have more of a starburst of red in the center. Older ones grow brilliantly red, set against the green outer skin, as dramatic as a dragonfruit.

The brilliant center color is fantastic. Radishes are cool-weather plants; these I planted late but were shaded by vigorous volunteer currant tomatoes that are taking over the bed!

When planting annuals, plant your favorites but don’t forget to play. There are so many varieties of veggies, herbs and flowers available now, especially heirloom and organic (non-GMO!). Why not try some and share the seed with friends?

- Arts and Crafts, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Living structures, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables

Curly Willow Trellis

A walk-through squash trellis. The vines will give it stability, and hang through. Thanks to generous friends, free seed opportunities and wonderful seed catalogs, we have many, many squash varieties to choose from this year. We also want to grow vertically where we can to save space so my daughter and I are creating trellises. No builder, I, but we’re hoping these will last for years to come.

This part of the trail was perfect for vertical growing space. This area of the upper trail isn’t lovely when not covered by vines. It is also quite warm when people are touring and it could use some shade and interesting focal point. Miranda had cut down a large curly willow tree a few months back (it was taking too much water from an avocado). We used a couple pieces of the trunk to inoculate with mushroom spores, and the rest was fair game for a trellis.

Curly willow (Salix matsudana ‘Tortuosa’) has wonderfully shaped branches that twist and curl naturally. You’ll see it often in bouquets, where it usually roots while in water. This willow enjoys more sun and a little less water than native willows do. Willows all produce salicin, the pain-killing ingredient that has now been synthetized as aspirin. Willows also produce a rooting hormone which can be used to encourage sprouting and rooting of other plants. Cut up a willow branch, soak it in water for a couple of days (if water is chlorinated, leave it sit for a day before adding willow) and use to water seedlings.

Miranda makes this look so easy! After we’d put these in, a friend recommended sliding the post pounder over the post before standing it up… for we short people who have trouble lifting the really heavy thing over our heads! Wanting to avoid cutting wood and nailing things together, we sunk four T-posts into the corners. The trellis is six feet across and eight feet wide; any wider and we would have put a center post on each side as well.

We wired on curly willow trunks in the corners, and wired long branches across the tops and the middle. We wired on the side posts and cross posts, cutting long branches from the willow. This willow was long dead; fresh willow could be sunk into the ground and it would root to make a living trellis, like the Withy Hide. We didn’t want that here, though.

We laid long whips from a Brazilian pepper tree across, then wove curly willow through for the top. We stood smaller branches upright along the sides and wired them on, keeping in mind spaces where the squash vines will want to find something on which to grab. Over the top we laid long slim branches from a Brazilian pepper that is growing wild in the streambed and really needs to come out. By pruning it and using the branches, we’re making use of the problem. In permaculture, the problem is the solution! I wanted to make an arched top and tried to nail the slim branches in a bended form, but this was difficult and didn’t work for me. I didn’t want to spend days finishing this… too much else to do! So we laid the branches over the top, wiring some on, and then wove curly willow branches long-wise through them. This weaving helps hold the branches in place, will give the vines support, and brings together the look.

We planted four kinds of squash along the poles. And it was done. It should stand up to wind. We may need to add some vertical support depending upon the weight of the squash vines. We planted four varieties of squash that have small (2-3 lb.) veg. We planted four seeds of each, two on either side. We also planted some herbs, flowers and alliums, and some perennial beans, the Golden Runner Bean.

Architecturally interesting when not covered by squash as well. If nothing else, it is lovely and interesting to look at; better in person than in the photos. We can’t wait for the squash to start vining! Now, onto the next trellis.

-

Sauteed Fennel

Sautéed fennel alongside squash bread pudding. The bread pudding recipe I have to work on, but not the fennel! It was so easy and so fantastic! Fennel is a sweet-tasting bulb with a satisfying crunch. This recipe is quick and easy, and absolutely delicious. I don’t have a good photo of it because, frankly, we ate it before I could make the light better.

Fennel apparently doesn’t have any companion plants according to every source I’ve checked. I grew a couple of bulbs in a polyculture bed without any problem, but to be on the safe side give it a spot by itself. Allow some to go to flower and you’ll attract lots of pollinators, and also have a host plant for swallowtail and other butterflies.

This recipe serves two as a side dish; feel free to up the number of bulbs. Enjoy!

Sauteed FennelAuthor: Diane C. KennedyRecipe type: Side dishCuisine: AmericanPrep time:Cook time:Total time:Serves: 2A simple, quick and utterly delicious vegetable side dish.Ingredients- One fennel bulb

- ⅛th cup olive oil

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Squeeze of lemon or lime

Instructions- Cut the top and bottom from the fennel bulb, then slice the fennel into small strips, about ¼ inch thick or so.

- Heat oil in a large frying pan and adjust heat to medium.

- Add fennel and cook, stirring occasionally to evenly brown, about ten minutes or until fennel is tender. Fennel should be slightly carmelized.

- Add salt and pepper to taste.

- Serve with a squeeze of lemon or lime, if desired.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fruit, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Herbs, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

The Mulberry Guild

The renovated and planted mulberry guild. One of our larger guilds has a Pakistani mulberry tree that I’d planted last spring, and around it had grown tomatoes, melons, eggplant, herbs, Swiss chard, artichokes and garlic chives.

Mulberry guild with last year’s plant matter and unreachable beds. This guild was too large; any vegetable bed should be able to be reached from a pathway without having to step into the bed. Stepping on your garden soil crushes fungus and microbes, and compacts (deoxygenates) the soil. So of course when I told my daughter last week that we had to plant that guild that day, what I ended up meaning was, we were going to do a lot of digging in the heat and maybe plant the next day. Most of my projects are like this.

Lavender, valerian, lemon balm, horehound, comfrey and clumping garlic chives were still thriving in the bed. Marsh fleabane, a native, had seeded itself all around the bed and had not only protected veggies from last summer’s extreme heat, but provided trellises for the current tomatoes.

Fleabane stalks from last year, with new growth coming from the roots. Marsh fleabane is an incredible lure for hundreds of our tiny native pollinators and other beneficial insects. Lots of lacewing eggs were on it, too. The plants were coming up from the base, so we cut and dropped these dead plants to mulch the guild.

The stalks of fleabane are hollow… perfect homes for small bees! The stems were hollow and just the right size to house beneficial bees such as mason bees. This plant is certainly a boon for our first line of defense, our native insects.

We also chopped and dropped the tomato vines. Tomatoes like growing in the same place every year. With excellent soil biology – something we are still working on achieving with compost and compost teas – you don’t have to rotate any crops.

Slashed and dropped tomato and fleabane. We had also discovered in the last flood that extra water through this heavy clay area would flow down the pathway to the pond, often channeled there via gopher tunnels.

The pathway is a water channel during heavy rains. It needs fixing. We decided to harvest that water and add water harvesting pathways to the garden at the same time. We dug a swale across the pathway, perpendicular to the flow of water, and continued the swale into the garden to a small hugel bed.

Swale dug on contour through the pathway and across the guild. Hugelkultur means soil on wood, and is an excellent way to store water in the ground, add nutrients, be rid of extra woody material and sequester carbon in the soil. We wanted the bottom of the swale to be level so that water caught on the pathway would slowly travel into the bed and passively be absorbed into the surrounding soil. We used our wonderful bunyip (water level).

Using a bunyip to make the bottom of the swale level. Water running into the path will now be channeled through the guild. Because of the heavy clay involved we decided to fill the swale with woody material, making it a long hugel bed. Water will enter the swale in the pathway, and will still channel water but will also percolate down to prevent overflow. We needed to capture a lot of water, but didn’t want a deep swale across our pathway. By making it a hugel bed with a slight concave surface it will capture water and percolate down quickly, running along the even bottom of the swale into the garden bed, without there being a trippable hole for visitors to have to navigate. So we filled the swale with stuff. Large wood is best for hugels because they hold more water and take more time to decompose, but we have little of that here. We had some very old firewood that had been sitting on soil. The life underneath wood is wonderful; isn’t this proof of how compost works?

The activity under an old log shows so many visible decomposers, and there are thousands that we don’t see. We laid the wood into the trench.

Placing old logs in the swale. If you don’t have old logs, what do you use? Everything else!

This giant palm has been a home to raccoons and orioles, and a perch for countless other birds. The last big wind storm distributed the fronds everywhere. We are wealthy in palm fronds.

Three quick cuts (to fit the bed) made these thorny fronds perfect hugelbed components. We layered all sorts of cuttings with the clay soil, and watered it in, making sure the water flowed across the level swale.

We filled the swale with fronds, rose and sage trimmings, some old firewood and sticks, and clay. As we worked, we felt as if we were being watched.

Can you spot the duck in this photo? Mr. and Mrs. Mallard were out for a graze, boldly checking out our progress. He is guarding her as she hikes around the property, leading him on a merry chase every afternoon. You can see Mr. Mallard to the left of the little bridge.

This male mallard and his mate, who is ‘ducked’ down in front of him, enjoyed grazing on weeds and watching we silly humans work so hard. After filling the swale, we covered the new trail that now transects the guild with cardboard to repress weeds.

Cardboard laid over the hugelswale. Then we covered that with wood chips and delineated the pathway with sticks; visitors never seem to see the pathways and are always stepping into the guilds. Grrr!

The cardboard was covered with wood chips and the pathway delineated with sticks. Where the trail curves to the left is a small raised hugelbed to help hold back water. At this point the day – and we – were done, but a couple of days later we planted. Polyculture is the best answer to pest problems and more nutritional food. We chose different mixes of seeds for each of the quadrants, based on situation, neighbor plants, companion planting and shade. We kept in mind the ‘recipe’ for plant guilds, choosing a nitrogen-fixer, a deep tap-rooted plant, a shade plant, an insect attractor, and a trellis plant. So, for one quarter we mixed together seeds of carrot, radish, corn, a bush squash, leaf parsley and a wildflower. Another had eggplant, a short-vined melon (we’ll be building trellises for most of our larger vining plants), basil, Swiss chard, garlic, poppies, and fava beans. In the raised hugelbed I planted peas, carrots, and flower seeds.

In the back quadrant next to the mulberry I wanted to trellis tomatoes.

This quadrant by the mulberry needed a trellis for tomatoes. I’d coppiced some young volunteer oaks, using the trunks for mushroom inoculation, and kept the tops because they branched out and I thought maybe they’d come in handy. Sure enough, we decided to try one for a tomato trellis. Tomatoes love to vine up other plants. Some of ours made it about ten feet in the air, which made them hard to pick but gave us a lesson in vines and were amusing to regard. So we dug a hole and stuck in one of these cuttings, then hammered in stakes on either side and tied the whole thing up.

Tying the trunk to two stakes with twine taken from straw bales. Love the blue color! The result looks like a dead tree. However, the leaves will drop, providing good mulch, the tiny current tomatoes which we seeded around the trunk will enjoy the support of all the small twigs and branches, and will cascade down from the arched side.

The ‘dead tree’ look won’t last long as the tomatoes climb over it and dangle close to the path for easy harvesting. We seeded the area with another kind of carrots (carrots love tomatoes!) and basil, and planted Tall Telephone beans around the mulberry trunk to use and protect it with vines. We watered it all in with well water, and can’t wait to see what pops up! We have so many new varieties from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds and other sources that we’re planting this year! Today we move onto the next bed.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

Planting Spores in the Garden

The mycelium is white in the sawdust and ready to go. If you remember the trenching, filling and designing the new veggie patch, then this post will make more sense to you.

The next step was to cardboard the pathways where Bermuda grass has been taking over, then mulch them as well. The mulch makes it all look so nice!

Covered with mulch, the cardboard is only a memory. Next it was time to plant. We’d already transplanted three-year old asparagus, and hopefully not shocked them so much that they won’t produce well this year. The flavor of fresh asparagus defies description.

Asparagus popping up some feather shoots from its new home. The strawberry bed was older and completely taken over by Bermuda grass, so it all was buried and I purchased new organic and extremely reasonably priced bareroot strawberries.

A bundle of twenty-five strawberries. I purchased two June-bearing types and three ever-bearing, heat-loving types, from www.groworganic.com. When they bloom this year we’ll have to nip off the buds so that next year when their roots have taken hold and fed the crown, we can have lots of strawberries.

Soaking the strawberry roots for a few minutes rehydrates them. We planted some in the asparagus bed, which will do nicely as groundcover and moisture retention around the asparagus, while the asparagus keeps the heat off the strawberries. Some we planted around the rock in the center of the garden. The rest will be planted around fruit trees as part of their guilds.

Strawberries surround the rock. We also planted rhubarb in the asparagus bed; these poor plants had been raised in the greenhouse for several months awaiting transplanting.

Rhubarb, really eager to be put in the ground. Hopefully the asparagus will protect them from the heat. I plan to raise more rhubarb from seed and plant them in other locations on the property, aiming for the coolest spots as they don’t like heat at all.

With a strong knife (weak blades may snap) cut a cross in wet cardboard the pull aside the edges. The way to plant through cardboard is to make sure that it is wet, and using a strong knife make an x through the cardboard. Use your fingers to pull the sides apart. Stick your trowel down and pull up a good shovel full of dirt (depending on how deeply your plant needs to go.

Insert a trowel through the hole and scoop out some dirt. The base of plants and the crowns of strawberries should all be at soil level. Seeds usually go down three times their size; very small seeds may need light to germinate). Gently plant your plant with a handful of good compost, then water it in. You won’t have to water very often because of the mulch, so check the soil first before watering so that you don’t overwater.

Don’t forget to water in the plants! For the first time in years I ordered from the same source Jerusalem artichokes, or Sunchokes as they’ve been marketed. They are like sunflowers with roots that taste faintly like artichoke. We planted some of them in one of the quadrants, and the rest will be planted out in the gardens, where the digging of roots won’t disturb surrounding plants.

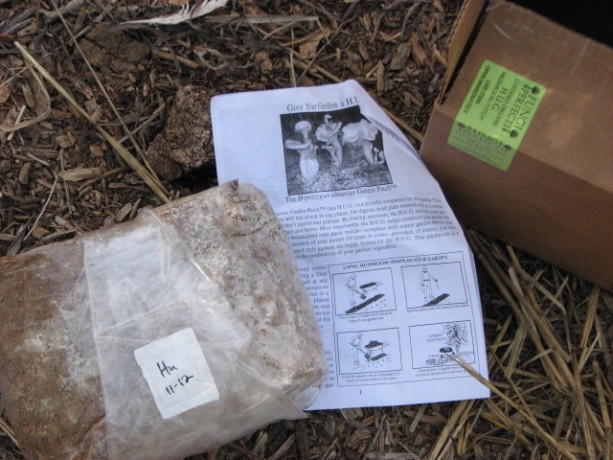

The oyster mushroom kit, or H.U.G. You’ll have to visit Fungi Perfecti to read up on it. Most excitingly, we’ve purchased mushroom spores from Fungi Perfecti, which is Paul Stamet’s business, the man who wrote Mycelium Running and several other books about growing mushrooms for food and for health. We bought inoculated plugs, but that will be another post. Almost as exciting are the three bags of inoculated sawdust to spread in the garden! They sell an oyster mushroom that helps digest straw and mulch, while boosting the growth of vegetables and improving the soil. You also may be able to harvest mushrooms from it! Talk about a wonderful soil solution, rather than dumping chemical fertilizers on the ground!

We’d already covered our veggie beds with wet cardboard and straw.

Really good soil from what is now a mulched pathway. To give the mycelium a good foundation I dug up good soil from one of the field beds, which needed an access path through the middle. By digging out the path I created new water-holding swales, especially when filled with mulch.

We pulled aside the straw. In the veggie garden we raked back the straw and lightly topped the wet cardboard with soil. On top of that we sprinkled the inoculated sawdust.

Good soil over cardboard. On top of that we pulled back the straw and watered it in.

Sprinkling spore-filled sawdust over the soil. The fungus will activate on the wet soil, eat through the cardboard to the layers of mushroom compost and pidgin poo underneath that and help make the heavy clay beneath richer faster.

The fungi will immediately begin to colonize the wet soil. We treated the two top most beds which have the worst soil, the sunchoke bed and the asparagus bed. In four to six weeks we may see some flowering of the mushrooms, although the fungus will be working even as I sit here. There are several reasons why I did this. One, it is just totally cool. Secondly, there is no way for me to purchase organic straw. By growing oyster mushrooms in it, I’m hoping the natural remediation qualities of the oyster fungus will help cleanse the straw as it decomposes. Oyster mushrooms don’t retain the toxins that they remove from soil and compost, so the mushrooms will still be edible. Fungus will assist rebuilding the soil and give the vegetables a big growing boost. I know I’ve preached that vegetables like a more bacterial soil rather than fungal. This is true, except that there are different types of fungus. If you put wood chips in a vegetable bed, you’ll activate other decomposing fungus that will retard the growth of your tender veggies; the same wood chips around trees and woody plants will help them grow. However these oyster mushrooms will benefit your veggies by quickly decomposing compost and making the nutrients readily available to the vegetables. Their hyphae will help the veggie’s roots in their search for water and nutrients, too.

Straw is over the top and watered. We can continue to plant in the beds as the fungus does its magic. The other two bags of inoculated spores are for shaggy mane and garden giant, which we’ll find homes for in compost under trees. More on that as we progress. It is so nice to be planting, especially since these are perennial plants where the most work is being done now. Now we just need some rain!

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Vegetables

The Sunken Bed Project, Part 3

The un-raised bed as of this morning. Today my daughter and I made good headway in the completion of the garden. In the morning the bed still had some veggies that needed transplanting, the ground needed smoothing, the giant clumps of asparagus plants we’d hauled out needed to be planted right away because they were already trying to come out of dormancy, and we certainly didn’t want to lose this spring’s crop.

Transplanting and some fine-tuning by the girls. We let the girls loose since we were watching out for coyotes. They loved the grubs and unfortunately, the valuable worms too. Lark, the barred rock in the foreground, was up to her old tricks of jumping onto my shovel and quickly kicking half the dirt off in search of bugs. Miranda painstakingly dug up lots of salad greens for transplanting. We both dug up and pulled out lots of Bermuda grass as we went. The trash cans are full of it.

The difference between the heavy clay and the good garden soil is striking. While digging those 2 foot deep trenches we unearthed a lot of clay. On the surface the colors of what had been good garden soil next to what lay under it was very clear. With the deep hugelkultur beds and the sheetmulching, all this clay will be turned into microbial rich soil.

We measured off and marked the pathways and beds with gypsum. Finally we were able to measure off and draw out the design of the garden. We used gypsum which is good for the soil. So many people use spray paint to mark the ground… just don’t! Toxic fumes and toxic chemicals in the soil. If you don’t have gypsum, use flour! The light is bright in the above photo so you can’t see the design so well. We had carefully drawn out several designs on graph paper. An intricate Celtic design was the most favorable one until I’d realized the garden wasn’t square but rectangular. It was just as well because it would have been a nightmare of measuring. This one has 2′ wide pathways from prime entry angles (a wheelbarrow can fit), each planter bed is easily reached from all sides, and the circular design is pleasing and fun.

There was this rock…. There was a big flaw in the plan. There was this boulder that had been placed during the original construction of the garden. It didn’t serve a purpose, it was always in the way, it was a shelter for Bermuda grass, and it wasn’t attractive. Now it was at the head of one of the pathways. It had to go. My daughter and I decided to move it to the center of the garden. After transplanting the heavy batches of asparagus, we dug out a hole for the rock to sit in; when placing boulders it is visually more attractive if the boulder is buried at least a quarter of its size into the ground to look natural. We placed wet newspapers around the hole so that the boulder would sit on them and they would block Bermuda grass from emerging.

One of the methods used to move the rock, and build up good bone density and muscle. Although the garden was sloped down from the boulder, the rock wasn’t round and didn’t want to roll. We dug out a pathway for it, and using a long crowbar and a digging bar we managed to turn it over. We pushed and heaved and balanced and flipped it until it was right at the rim of the hole, and then things became difficult because it wasn’t positioned in the way we wanted it. The rock has a flat side, and is long. Miranda suggested that the tall side should stand up for birds to perch on, and I liked the Half-Dome look to it. We heaved the rock into the hole, then walked it around, tipped it up, centered it, and eased it into place, using the bars and all of our strength. Luckily the boulder didn’t roll on a foot, or the bar slip and break my collarbone. Finally we tiredly decided that the position it was in was good enough and we were both happy. Exhaustion had much to do with this decision. Miranda propped it up with clay chunks as I held it in place with the digging bar, then backfilled around it. It looks fantastic; a good central point for the garden, and a source of thermal retention.

The rock in place, gathering positive cosmic forces and good karma. At least, I hope so. We messed up some of our pathway lines, but we can easily redraw them. The sun was setting and the mosquitoes humming; the Pacific chorus frogs began calling by the hundreds, and the wigeon came in to feed on the pond. There were still chores and dinner to be had, but exhausted as we were, we were pretty darn proud of ourselves for moving that big guy by ourselves. Next comes the sheet mulch.

A Maxfield Parrish sunset. - Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving

The Pros and Cons of Raised Beds

The raised beds. Raised garden beds can be wonderful things. They also can be inappropriate. I’m in the process of taking ours down and replacing them with… well, I’ll describe it later on. Let’s get back to the pros and cons of raised beds.

Here are some of the pros:

Raised beds look just great. They are neat, tidy, organized and restful to the eye.

If raised high enough they are accessible to those who can’t work on the ground or bend over, and to those who are non-ambulatory.

If lined with hardware cloth they keep gophers and mice from tunneling under your food and making it magically disappear.

They help with some weed control.

If you live in a rainy area, they help with drainage.

If you have miserable soil, you can garden anywhere by building a raised bed without having to dig.

If you live in a cold area, depending upon what materials you use for the sides of the raised beds you can tap into the thermal heat and have warmer soil longer.

You can build reusable covers for the beds and turn them into cold frames, or shade structures.

Now here are some of the cons:

You need to fill raised beds with a lot of soil, and if you have to buy it, that is a large expense. The soil will compact and disappear over the course of a year, so you have to keep topping up the beds to keep the soil level high. Heavy work that is expensive.

Wire underneath the raised beds will last a few years and then will be compromised by rodents, so the bed will have to be emptied and rewired if rodents are a problem.

If you live in a warm, dry climate, the sides of the raised bed acts like a clay pot. It will wick moisture from the dirt and heat the dirt up so that plant roots around the perimeter will cook.

If you live in a warm climate you have to pour on the water because of the point mentioned above; a raised bed dries out much more quickly than in-ground gardens.

We are wealthy in clay. A Bermuda grass root hangs like a piglet’s tail from this clump. I built raised beds from old bookshelves many years ago, and that was my only veggie garden on the property as I raised my children. I’d grown plants in-ground before that, trenching and turning, and losing the fight against gophers and Bermuda grass. The raised beds were lined with wire. For awhile it worked, but the Bermuda grass took over and infiltrated all the beds. The wire began to rot and rodents chewed away at the sweet potatoes. Worst of all, the soil level would decrease, and since the beds weren’t very deep, then root veggies would grow into the wire and I’d lose half of them as they broke off during the harvest. I couldn’t keep up with refilling the beds. I composted in place, buried wood and vines, and that worked well, but I still needed to add compost. The beds drank up water during our long, hot summers.

The trenching begins. This summer I realized that I was using a gardening technique that was best suited to rainy climates. Here in the dry Southwest, a traditional gardening method was to plant in sunken beds. We need to capture water, not make it run off. Also, the Bermuda grass became so invasive that I realized that only sheet mulching would make any difference in controlling it.

Of course I decided that my daughter and I couldn’t possibly have an easy winter, but must rip out the beds and start digging.

In the trenches. I’m an advocate of no-dig gardening; however sometimes you have to dig bad soil to create good soil. The no-dig policy can happen once the infrastructure is in place. So here’s what I’m planning on doing: I’m combining hugelkultur with sunken gardens and sheet mulching to create what I hope will be a veggie garden with a much lower water consumption, and weed-free.

First we determined the direction of water flow down the hill, and planned on creating trenches that would capture that water. The trenches, or swales, would need to be level on the bottom so that any water flowing in from the downhill side, would travel all along the swale even to the drier side, where the surface soil was higher. We created a bunyip to estimate the difference in slope between the top and bottom of the garden. Although I had drawn up intricate plans for a square garden, that shape just wouldn’t work so we went with a rectangle. Then we began to dig. The first ten inches wasn’t bad, but after that we hit clay. I had to buy a mattock. I also ended up icing my back for a couple of days. Some of the clay we’ll save for use on any future earthworks we may want to do, and some we’re saving for an artist friend.

The soil was good for about ten inches, then we hit clay. The trenches are two feet deep, and about one to one and a half feet wide. It is amazing how you start out large, and then after a few very hot afternoons scraping clay and throwing it up and over four feet, the trenches become more narrow. My plan is to fill the bottom foot of the trenches with old wire, wood, branches, old textiles and other biodegradable debris. The old wire will rot, and will also help repel gophers. On top of all this will be layered some of the clay, and watered in with compost tea brewed in the 700-gallon water tank that is full of rainwater from the last rain (two months ago!). On top of that will be good soil, smoothed below the surrounding surface level. Water from the road will be diverted into the swales, which will allow it to flow across the garden and be absorbed by the fill materials. But what about the Bermuda grass? There isn’t a mountain of cardboard all over my garage for nothing! The entire garden will be sheet mulched, and all veggies will be planted through the cardboard and newspaper. The existing asparagus bed will need to be carefully relocated, but everything else can either be harvested or dug under.

These first two trenches will collect rainwater from the pathways and channel it the length of the garden. That’s the plan, anyhow. I’ll let you know how it goes.

-

Thai Coconut Soup with Tofu and Mushrooms

A comfort food without the high caloric price tag. This is a soup recipe that has been requested by friends, and is so good that I crave it. So I share it with you. Wonderful even during the summer, it also is fantastic comfort food when sick or on a cold day. You can tweak this dish with lite coconut milk, lime zest instead of lemongrass, or if you have access to Thai ingredients use kaffir lime and Thai basil.

Lemongrass is easy to grow and to use. Just the base of the peeled stalk is used as a flavoring. Cut it only in half so the pieces are easily found in the soup and put aside. I’ve had it without tofu, and without mushrooms, and it is still wonderful. Put the lime in the coconut, and drink it all up! Don’t put too many extra veggies in it; it is a simple soup.

Thai Coconut Soup with Tofu and MushroomsAuthor: Diane C. KennedyRecipe type: SoupCuisine: ThaiPrep time:Cook time:Total time:Serves: 4A simple, delicious vegetarian Tom Kha soup. The lemongrass isn't meant to be eaten because its too tough. The kaffir lime leaf may be eaten only if you use a young one and slice very thinly before adding it.Ingredients- 1 can (1 ½ cups) unsweetened coconut milk

- 2 tsp. grated fresh ginger

- 1 fresh lemongrass stalk, peeled and halved (or 2 tsp. dried, or 1 tsp. lime zest)

- 1 bruised fresh or dried kaffir lime leaf, (if young can be sliced very thinly(or ½ tsp. lime juice)

- Two - three Thai basil leaves (optional)

- 3 cups mild vegetable stock

- ½ to 2 teaspoons Thai red curry paste, or Thai coconut curry paste, or curry powder (depending on hotness desired)

- 1 package (12 – 14 oz) extra firm tofu (not silken)drained and cut into small cubes

- 15 oz canned straw mushrooms, drained and rinsed, or half-cup sliced button mushrooms

- 2 tsp. sugar or other tasteless sweetener

- 2 Tablespoons light soy sauce (I use Bragg’s Amino Acids instead)

- Salt to taste (opt.)

- Fresh lime juice to taste (opt.)

Instructions- Combine lemongrass, ginger, kaffir leaf, Thai basil leaves, and coconut milk with broth in a large saucepan and bring to a boil.

- Reduce heat to medium-low and simmer for 5 – 10 minutes.

- Add the curry paste a half-teaspoon at a time, stirring well and tasting for desired hotness.

- Stir in the tofu, mushrooms, sugar, and soy sauce.

- Simmer for about 10 minutes more.

- Taste before adding additional optional salt.

- Serve as is or over hot rice.

- Offer fresh lime to squeeze on top as desired (it makes the flavors pop).

- Animals, Chickens, Cob, Compost, Composting toilet, Fruit, Gardening adventures, Giving, Grains, Health, Herbs, Houses, Hugelkultur, Humor, Living structures, Natives, Natural cleaners, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Rain Catching, Recipes, Seeds, Soil, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian, Worms

San Diego Permaculture Convergence, Nov. 9 – 10, 2013

There is a fantastic, information-packed permaculture convergence coming up at the beautiful Sky Mountain Institute in Escondido.

It will be two days packed with great information for a very reasonable price; in fact, scholarships are available. Check out the website at convergence@sdpermies.com. On that Sunday I’ll be teaching a workshop about why its so important to plant native plants, how to plant them in guilds using fishscale swales and mini-hugelkulturs. Come to the convergence and be inspired!

It will be two days packed with great information for a very reasonable price; in fact, scholarships are available. Check out the website at convergence@sdpermies.com. On that Sunday I’ll be teaching a workshop about why its so important to plant native plants, how to plant them in guilds using fishscale swales and mini-hugelkulturs. Come to the convergence and be inspired! - Gardening adventures, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Recipes, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian

Dinner with the Pandas: Harvesting Your Own Bamboo

Hello.

Before you cry, “Imposter!”, let me assure you that I have authorization to be here. Mostly. I happen to be Diane’s daughter Miranda, guestblogging and wordsmithing for you today. You might recognize my powdery feet or recollect me when keeping company with chickens (or from diverse other adventures). As much as I enjoying rolling in dust and home decorating with hens, today I’m here to talk about an unusual topic for Vegetariat – food.

The handy rhyme isn’t the only reason I’m sometimes known as Miranda the Panda – I also have a great partiality for a bit of bamboo, much like the vegetarian carnivore from whom I draw my catchy moniker. Luckily, we happen to have a fair bit of the stuff around Finch Frolic these days (bamboo, not pandas). Bamboo shoots are a common – and delicious! – component of Asian cuisines, and bamboo has been used for many culinary purposes, such as flavoring rice, wherever it grows. During this past summer, I was overcome with the need to find more things to eat on the property and began a foray into harvesting our own bamboo shoots.

Our giant species of bamboo arches over many of our paths — perfect for building material, and any shoots that venture into the soil of the paths are prime targets… 🙂 Before I stepped outdoors and started gnawing on the nearest clump, I had to be sure that our bamboo is an edible variety, and hopefully a tasty edible variety. You need the scientific name of your bamboo for that, but once we ferreted out ours (Bambusa beecheyana), it was easy to find notation of its edibility and delectability online. One helpful and extensive listing is on Guadua Bamboo. Happily, there is a large number of edible and tasty bamboo species.

Proof of mange-ability in hand, the next obstacle was divining the best way to get bamboo shoots from the ground to my mouth. Harvesting can be more or less of a challenge, depending on what variety of bamboo one has and how it’s established (e.g., moisture and soil conditions, obstacles like stones around it). To harvest shoots, it’s best to pick fat green ones poking no more than a foot above the ground. You want to catch them before they get too woody, but old enough to have a bit of meat on them, so to speak. The shoot is mostly leaf (tightly layered sheaths), so bulkier shoots are more rewarding.

Removing our bamboo from the ground and its parent plant turned out to be on the more side of challenging.

Miranda and Diane bust out the Finch Frolic arsenal on the recalcitrant shoot.

First, the inimitable spade is set to the task.

Legs weary and spade abandoned, the small sickle saw is recruited, to little effect. Diane had just returned home and gleefully plunged into the fray, skirt, white sandals and all.

Finally, Diane wades into battle with the winning implement.

The shoot, freed from the earth and its parent plant. Once we finally achieved success, processing could begin! It is somewhat tiresome to strip a shoot down to the edible white core, because the leaves cling so tightly and are fibrous. It’s like shucking the most stubborn ear of corn in the world. It’s good to slit the tougher outer leaves with a very sharp knife and peel them away.

Slitting the fibrous outer leaves with a filet knife.

Peeling. The inner leaves come away more easily – rather like the layers of canned hearts-of-palm – as you get closer to the heart of the bamboo shoot. The innermost leaves are basically fetal, and so are edible because they haven’t gotten tough yet. They make the tip of your shoot look hairy.

Many layers of increasingly tender leaves.

The edible shoot. A peeled bamboo shoot can be cut up in whatever way the chef desires. The shoot grows more fibrous towards the base, where there is probably some inedible hard material. My current rule of thumbs-carefully-tucked-away is if a sharp knife can pretty easily get through it, it’ll be fine to eat.

A shoot cut in three different ways. The material behind the knife (upper left) is too fibrous to eat. You just have to boil your slices before cooking and consumption because they contain a mild toxin that dissipates with boiling. The first time, we tried boiling in lightly salted water for only 30 minutes, and while the shoots were tender and not really bitter, they left a teeny tingling sensation in our mouths, like stir-fried Pop Rocks. The last time I cooked them, I boiled them for a whole 50 min. to much more satisfactory, un-tingly results.

Boiling to remove toxins. Bamboo is delicious and a lot of fun (in a somewhat laborious way) to harvest. The beauty of harvesting your own bamboo shoots is that you are saving yourself a trip to specialty markets and controlling your bamboo’s growth at the same time!

Frying up — yummy! So that’s another thing going on here at FFG. Thanks for wandering the bamboo lane with me.

TTFN!

Miranda (the Panda), B.S.