Perennial vegetables

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Soil, Water Saving

Plant Guild #7: Vines

Our varieties of squash several years ago. You may think that vines and groundcover plants are pretty interchangeable, and they can share a similar role. However, as we covered in the Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers these plants do not have to vine, but just cover large spaces close to the ground and coming from a single trunk or stem.

Sweet potatoes and yams make fantastic ground covers. The leaves are edible. Some root in one place, and some spread tubers over a larger area, so choose what is appropriate for digging up your harvest in your guild. They will die of frost. Vines can be large and heavy, small and delicate, perennial or annual. In a food plant guild vines are often food-bearing, such as squash. If you recall the legendary Three Sisters of planting – corn, beans and squash – there are two vines at work here. The corn forms a trellis for the light and grabby bean plant to climb upon (the bean fixing nitrogen in the soil as well as attracting pollinators with its flowers). The squash forms a low canopy all around the planted area. The big leaves keep moisture in, soften the raindrops to prevent erosion and deoxygenation, drop leaves to fertilize the soil, provide a large food crop, and attract larger pollinators. Even more than that, the squash protects the corn from raccoons. These masked thieves can destroy an entire backyard corn crop in a night, just when the corn is ripe. However, they don’t like walking where they can’t see the ground, so the dense squash groundcover helps keep them away.

Pipian from Tuxpan squash supported by a plum and a pepper tree. Vines are very important to use on vertical space, especially on trees. With global warming many areas now have extremely hot to scorching sun, and for longer periods. Intense sun will scorch bark on tender trees, especially young ones. By growing annual vines up the trees you are helping shade the trunk while producing a crop, and if the vines are legumes you are also adding nitrogen fertilizer.

Can you spot the squash in the lime tree? It is crescent shaped and pale. Be sure the weight of the mature vine isn’t more than the tree support can hold, or that the vine is so strong that it will wind its way around new growth and choke it. Peas, beans and sweetpeas are wonderful for small and weaker trees. When the vines die they can be added to the mulch around the base of the tree, and the tree will receive winter sunlight. When we plant trees, we pop a bunch of vining pea (cool weather) or bean (warm weather) seeds right around the trunk. Larger, thicker trees can support tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, and squash of various sizes, as well as gourds. Think about how to pick what is up there! We allowed a alcayota squash to grow up a sycamore to see what would happen, and there was a fifteen pound squash hanging twelve feet above the pathway until it came down in a heavy wind!

These zuchinno rampicante, an heirloom squash that can be eaten green or as a winter squash, form interesting shapes as they grow. These ‘swans’ and Marina are having a stare-off. Nature uses vertical spaces for vines in mutually beneficial circumstances all the time, except for notable strangler vines. For instance in Southern California we have a wild grape known as Roger’s Red which grows in the understory of California Live Oaks. A few years ago there appeared in our local paper articles declaiming the vines, saying that everyone should cut them down because they were growing up and over the canopy of the oaks and killing them. The real problem was that the oaks were ill due to water issues, or beetle, or compaction, and had been losing leaves. The grape headed for the sun, of course, and spread around the top of the trees. The overgrowth of the grape wasn’t the cause of the problem, but a symptom of a greater illness with the oaks.

Zucchini! Some vines are not only perennial, but very long-lived and should be placed where they’ll be happiest and do the most good. Kiwi vines broaden their trunks over time and with support under their fruiting stems can be wonderful living shade structures. A restaurant in Corvallis, Oregon has one such beauty on their back patio. There is something wonderful about sitting in the protection of a living thing.

Wisteria chinensis is a nitrogen-fixer with edible flowers (and poisonous other parts), has stunning spring flowers and can make a nice deciduous vine to cover a canopy. It does spread vigorously, but can be trained into a standard, and are fairly drought tolerant when mature. Passionvines can grow up large trees where they can receive a lot of light. Their fruit will drop to the ground when ripe. The vines aren’t deciduous, so the tree would be one where the vine coverage won’t hurt the trunk.

Dragonfruit aren’t exactly a vine, but they can be trained up a sturdy tree. Vines such as hops will reroot and spread wherever they want, so consider this trait if you plant them. Because the hops need hand harvesting and the vines grow very long, it is probably best to put them on a structure such as a fence so you can easily harvest them.

So consider vines as another important tool in your toolbox of plants that help make a community of plants succeed.

Next in the Plant Guild series, the last component, Insectiaries. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants

Artichokes are mining plants, but also have a low enough profile to be a groundcover plant. They make excellent chop-and-drop. Flanking are lavender, scented geranium (left), and borage. In most ecosystems that offer easy food for humans, the ground needs to be covered. Layers of leaves, organic matter from animals (poo, fur, carcasses, meal remains, etc.) , dropped branches and twigs, fallen flowers and fruit, and whatever else gravity holds close to the earth, compost to create soil and retain water and protect the soil from erosion and compaction. Areas that don’t have this compost layer are called deserts. If you want to grow an assortment of food for humans, you have to start building soil. Even in desert communities where there are some food plants growing, such as edible cactus, mesquite beans, etc., there is biodiversity on a more microscopic scale than in old growth forests. In deserts the soil needs to absorb what little rain there is and do it quickly before it evaporates, and plants have leaves adapted to have small leaf surfaces so as not to dry out, and there are few leaves to drop. Whereas in areas where there are large forests the weather is usually wetter, tall plants and thick underbrush provide multiple layers of protection both on the plants and when they fall to layer the earth.

Nasturtium reseeds itself annually, is edible with a bite of hotness, detracts aphids from other plants, and is charming. Don’t let it get away in natural areas, though. A quick way to build soil in plant guilds is to design for plants that will cover the ground. This isn’t necessarily the same groundcover as you would use to cover embankments. For instance, iceplant can be used in a pinch, but it really isn’t the best choice in most plant guilds unless you are in a very dry climate, and your plant guild is mostly desert-type plants: date palm, etc. Annuals can be squash or other aggressive food-producing vines such as unstaked tomatoes. However you don’t need to consider just ground-hugging plants; think sprawling shrubs.

Scented geraniums are a great ‘placeholder plant’. These Pelargoniums (not true geraniums) come in a wide variety of fragrances. We’ve found bird nests in these! When guests tour through Finch Frolic Garden, they often desire the lush foresty-feel of it for their own properties, but have no idea how to make it happen. This is where what I call ‘placeholder plants’ come in. Sprawling, low-cost shrubs can quickly cover a lot of ground, protect the soil, attract insects, often be edible or medicinal, be habitat for many animals, often can be pruned heavily to harvest green mulch (chop-and-drop), often can be pruned for cuttings that can be rooted for new plants to use or to sell, and are usually very attractive. When its time to plant something more useful in that area, the groundcover plant can be harvested, used for mulch, buried, or divided up. During the years that plant has been growing it has been building soil beneath it, protecting the ground from compaction from the rain. There is leave mulch, droppings from lizards, frogs, birds, rabbits, rodents and other creatures fertilizing the soil. The roots of the plant have been breaking through the dirt, releasing nutrients and developing microbial populations. Some plants sprawl 15′ or more; some are very low-water-use. All of this from one inexpensive plant.

Squash forms an annual groundcover around the base of this euphorbia. Depending upon your watering, there are many plants that fit the bill, and most of them are usable herbs. Scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.), lavender, oregano, marjoram, culinary sage, prostrate rosemary, are several choices of many plants that will sprawl out from one central taproot. Here in Southern California, natives such as Cleveland sage, quail bush (which harvests salt from the soil), and ceanothus (California lilac, a nitrogen-fixer as well), are a few choices. Usually the less water use the plant needs, the slower the growth and the less often you can chop-and-drop it. With a little water, scented geraniums can cover 10 – 15 feet and you can use them for green mulch often, for rooted cuttings, for attracting insects, for medicine and flavoring, for cut greenery, for distillates if you make oils, etc.

Sweet potatoes make a great ground cover. Choose varieties that produce tubers directly under the plant rather than all along the stems so that you don’t have to dig up your whole guild to harvest. Groundcover plants shouldn’t be invasive. If you are planting in a small guild, planting something spreading like mint is going to be troublesome. If you are planting in larger guilds, then having something spreading in some areas, such as mint, is fine. However mint and other invasives don’t sprawl, but produce greenery above rootstock, so they are actually occupying more space than those plants that have a central taproot and can protect soil under their stems and branches. Here at Finch Frolic Garden, we have mint growing freely by the ponds, and in several pathways. Its job is to crowd out weeds, build soil, and provide aromatherapy. I’d much rather step on mint than on Bermuda grass, and besides being a superb tea herb, the tiny flowers feed the very small bees, wasps and flies that go unsung in gardens in favor of our non-native honeybees (there are no native honeybees in North America).

Here’s a general planting tip: position plants with fragrant leaves and flowers near your pathways for brush-by fragrance. You should have a dose of aromatherapy simply by walking your garden path. Mints are energizing, lavenders calming, so maybe plan your herbs with the pathways you take in the morning and evening to correspond to what boost you need at that time.

Consider groundcover plants and shrubs that will give you good soil and often so much more.

Next up: Vining Plants.

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

What makes up a plant guild. - Animals, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Humor, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Ponds and Potatoes; A Finch Frolic New Year’s Celebration

Our sixty degree weather here in Fallbrook, CA , gave us the opportunity to work in our garden. A year ago – 2014 – it snowed on New Year’s Eve. This year the nights are frosty, the days mercifully warmer, and the rain frustratingly rare. Our promised El Nino rains are expected to hit in force within the next couple of months. Weather they do or not, focusing on catching every precious drop in the soil, and protecting the ground from erosion and compaction, is paramount.

Our sixty degree weather here in Fallbrook, CA , gave us the opportunity to work in our garden. A year ago – 2014 – it snowed on New Year’s Eve. This year the nights are frosty, the days mercifully warmer, and the rain frustratingly rare. Our promised El Nino rains are expected to hit in force within the next couple of months. Weather they do or not, focusing on catching every precious drop in the soil, and protecting the ground from erosion and compaction, is paramount.

Permaculture in rows. Pretty nice soil, which had been silt from the street a couple of years ago, mixed with chicken straw, topped with leaves. No chemicals! The last day of 2015 Miranda and I spent working one of our vegetable garden beds, and reshaping our kitchen garden. When we redesigned this garden by removing (and burying) the raised beds, hugelkulturing and planting, we made a lovely Celtic design.

The unplanted kitchen garden newly designed in January, 2013. However the plants just won’t respect the design, so we’ve opted to lessen the pathways, turning the beds into keyhole designs for more planting space. I’ll blog more about that in the future. Because the pathways have been covered in cardboard and woodchips (sheet mulched), the soil below them is in very good shape, not dry and compacted.

How deep do roots grow? This clump of oxalis (sour grass) is white because it was growing without light under the pathway sheet mulch. The corms at the end of the long roots are about 8 inches below the plant. Good soil means deep roots; I’ve never seen this plant have anything but shallow roots. This bed has been home to sweet potatoes and various other plants, so although I try to practice the no-dig method, where you have root vegetables you must gently probe the soil for goodies. We left some of the roots, so sweet potatoes will again rise in this bed.

Miranda planting potatoes and shallots in rows. Between these rows and around the outisde other veggies were planted. We planted in rows. Usually I mix up seeds, but this time I wanted to demonstrate polyculture in row form. We planted three rows of organic potatoes (purchased from Peaceful Valley Organics), with a row of shallots between them. Between the root vegetable rows we planted a row of fava beans, and a row of sugar pod peas. Around the edges Miranda planted rows of bull’s blood beets, Parisienne carrots, and maybe some parsnips. This combination of plants will work together in the soil, following the template of a plant guild. We left the struggling eggplant, which came up late in the year after the very hot summer and has so far survived the light frost.

Sticks. So important for the soil. These went in vertically around the planting bed to act both as one type of gopher deterrent (a physical barrier) and also as food and as water retention for the veggies. On top of the bed we strew dead pond plants harvested from our small pond near our house, which will be receiving an overhaul soon (hopefully before the Pacific chorus frogs start their mating season in force). We didn’t water the seeds in, as there is rain predicted in a few days. The mulch on top will help protect the seeds from hungry birds.

The finished bed topped with dead pond weeds (which don’t have seeds that will grow on dry land!). The sticks are to steady future bush peas. A good way to spend the last day of the year: setting seeds for food in the spring.

Before: The little pond, which is also a silt basin, almost completely filled by an enthusiastic clump of pickerel. This pond is wonderful habitat for birds, frogs, dragonflies, and so many other creatures, and as a water source for raccoon, possum, coyotes, ducks, and who knows what else that visits in the night. Then on January 1 I decided it was a good opportunity to clear out the excess pickerel that had taken over our lower small pond. With the well off for the winter, and very light rainfall, this pond has gone dry. A perfect opportunity for me to get in there with a shovel, especially knowing that I already had a chiropractor’s appointment set for Monday (!).

Making some headway. The mud was slick and spongy, but not unsafe, and not nearly as smelly as I had anticipated. Pickerel is not a native to San Diego, but it is a good habitat pond plant and it has edible parts. I wasn’t tempted, however. Its roots are thick and form a mat several inches thick hiding rhizomes that are up to an inch in diameter. I’d cut into the mass from several sides, pull the mass out with my gloved hands and throw the heavy thing out of the pond. Its good to be in contact with the earth, in all its forms. I couldn’t think of a better way to use the holiday afternoon.

Thick root mass hiding large rhizomes made removal a real exercise. This is why I practice yoga and attend Zumba class with Ann Wade at the Fallbrook Community Center! I moved at least a ton of material in four hours. Just before sunset I decided that I was done. About an hour before that, my body had decided that I was done, but I overrode its vote to finish. I left some pickerel for habitat and looks, and will try to contain it by putting some sort of a physical barrier along the roots, such as urbanite.

Removal of one of the three really nasty plants around the edge was a victory. The ends of their leaves are like needles, and impossible to walk past or work around, and dangerous for little kids. This root ball was harder to dig out than the mucky pickerel, and the success even sweeter. Revenge for all the pokes! We also might harvest some of the silty clay for use in the upper pond, although the prospect of carting heavy wet mud uphill isn’t as appealing as it might sound. That needs to happen today or tomorrow, as the aforementioned rain is expected, and I want to fill this pond again for the frogs.

After: Finished with the digging. Still more work to do -including cleanup of the mountain of organic matter – before refilling. One good thing about the pond going dry is that there are no more mosquito fish (gambuzia) in it. Mosquito fish are very invasive, and love to eat frog’s eggs and tadpoles far better than they do mosquito larvae. When the pond fills with non-chemically treated water (rain and well water), some of the microscopic aquatic creatures will repopulate the water. I’ll add some water from the big pond as well to make sure there are daphnia and other natural water friends in it, which will do a much better job at mosquito control without sacrificing our native frogs. I can’t get all the gambuzia out of our big pond, but at least they are out of the other two. Once dragonflies start in again, their young will gladly eat mosquito larvae.

So here on the morning of the second day of 2016, I lay in my warm bed prior to rising to start the chores of the day, stiff as an old stiff thing as my body adjusts to strenuous manual labor again, looking forward to more gardening duties to prepare Finch Frolic Garden for the reopening March 1, and for the rains.

The best part of heavy gardening duties is that I can finish off the Christmas cookies guilt-free!

- Animals, Birding, Building and Landscaping, Chickens, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Houses, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Podcasts with Diane Kennedy

Two podcasts with me talking about permaculture, Finch Frolic Garden, and how you can save money and the world through gardening! 🙂 Please let me know what you think:

This is a podcast with Sheri Menelli of earthfriendlyhomeowner.com, where I talk pretty much without a pause for breath for about the first ten minutes. Recorded in May, 2015.

http://www.earthfriendlyhomeowner.com/ep7-interview-with-diane-kennedy-of-finch-frolic-gardens-and-vegetariat-com/

This is a podcast with Greg Peterson of Urban Farm Podcasts, released Jan. 7, 2016, and you can listen to it several ways:

Urban Farm U:

http://www.urbanfarm.org/category/podcast/

iTunes:

https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/urban-farm-podcast-greg-peterson/id1056838077?mt=2

You can sign up for free to hear all their great podcasts here.

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Natives, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants

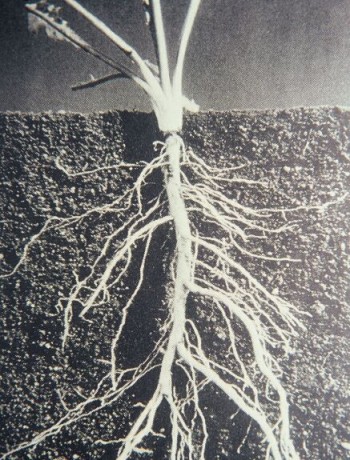

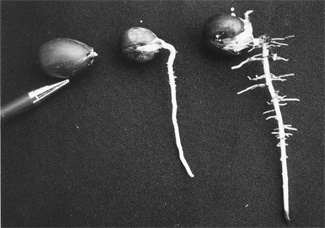

The beauteous taproot. In the last post we explored one way plants take nitrogen out of the air and fix it in the soil. Now we’ll explore how plants take nutrients from deep in the soil and deliver them to the soil surface. This is another way that plants create high nutrient topsoil.

All rooted plants gather nutrition from the soil, store it in their leaves, flowers and fruit, and then create topsoil as these products fall to the ground. Every plant is a vitamin pill for the soil. When you pull ‘weeds’, clear your garden, prune and otherwise amass greenery and deadwood, you are gathering vitamins and minerals for your soil. Bury it. All of it. If its too big to bury, then chip it and use it as top mulch. Allow that nutrition to return to the soil from whence it came. No stick or leaf should leave your property! Period.

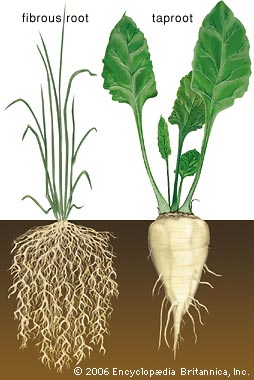

Fiberous roots hold soils together, and taproots dig. There are mainly two kinds of root systems: fibrous (like many grasses) and taprooted. Some taprooted plants grow very deeply. Those plants that are deemed ‘mining’ plants go the extra mile. I envision mining plants as the gruff gentlemen of the plant guild: tough and weathered, dressed in pith helmet and explorer clothes with a larger-than life character and a heart of gold.

A monument to Sir Henry Morton Stanley. I don’t know if he had a heart of gold or was gruff. Okay, too many old movies on my part. The roots of mining plants are large taproots that explore the depth of the soil searching for deep water. Depending upon the size of the plant, these roots can break through hardpan and heavy soils. They create oxygen and nutrient channels, digging tunnels that weaker roots from less bold plants and soft-bodied soil creatures can follow. When these large roots die they decompose deep in the ground, bringing that all-important organic material into the soil to feed microbes. Meanwhile these Indiana Jones’s of the root world are finding pockets of minerals deep in the soil – far below the topsoil and where other roots can’t reach – and are taking them into their bodies and up into their leaves. When these leaves die off and fall to the ground they are a super rich addition to the topsoil. Often the deep taprooted plants have a sharp scent or taste. Many weeds found in heavy soils are mining plants, sent by Mother Nature to break up the dirt and create topsoil. Dicotyledonous (dicot) plants have deep taproots, if you are into that kind of thing. The benefits of a plant having a deep taproot is not only to search for deep water, but to store a lot more sugar in the root, be anchored firmly, and to withstand drought better.

So who are these helpful gentlemen adventurers of the plant guilds? Comfrey and artichoke are two commonly used mining plants. Also members of the, radish, mustard, and carrot family such as, parsnip, root celery, horseradish, burdock, parsley, dandelion, turnip, and poppy to name a few. There is also milkweed (Asclepias), coneflower, chicory, licorice, pigeon pea, and for California natives there is sagebrush, Matilija poppy, oaks, mesquite, Palo Verde and many more. Most deep taprooted plants don’t transplant well because their straight taproot is often much longer than the top of the plant. Check out a sprouted acorn. The taproot is many times as deep as the top is high.

Three day’s difference in germinating acorns. Talk about taproot! Image from www.landscapeonline.com. Yet some mining plants such as comfrey and horseradish can be divided or will sprout from pieces of the root left in the ground. Deep taprooted weeds seem to all be like that, at least on my property!

Horseradish: the root is edible and medicinal, and the leaves are a spicy treat!

Grating horseradish for sauce, and still tearing up! Now for a little comfrey prosthelytizing: Comfrey keeps coming back when chopped, so it is often grown around fruit producing trees to be chopped and dropped as a main fertilizer. Its leaves are so high in nutrition that they are a compost activator, an excellent hen and livestock food (dried it has 26% protein), and have been heavily used in traditional medicine. Also called Knitbone, the roots contain allantoin, a substance also found in mother’s milk, which among other benefits helps heal bone breaks when applied topically.

A handsome comfrey plant working in the garden. The plant also has flowers that bees and other insects love. It spreads by seeds as well as divisions, and non-permaculture gardeners don’t like it escaping in their gardens. I only wish that mine would spread faster, to create more fertilizer. Comfrey grows the best greens with some irrigation and better soil, so it is perfect for use around fruit trees.

So when planting a guild you can easily plant miners that are edible. If you harvest those deep taproots, such as carrots or parsnips, then be sure to trim the greens and let them fall on the spot, so the plant will have done its full duty to the soil. Unless the plant can take division, such as the aforementioned comfrey, then planting seeds are best. Deep taprooted plants in pots are often stunted and either don’t survive transplanting well, or will take a long time to grow on top because they need to grow so much on the bottom first.

Next up: the exciting groundcover plants!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy!

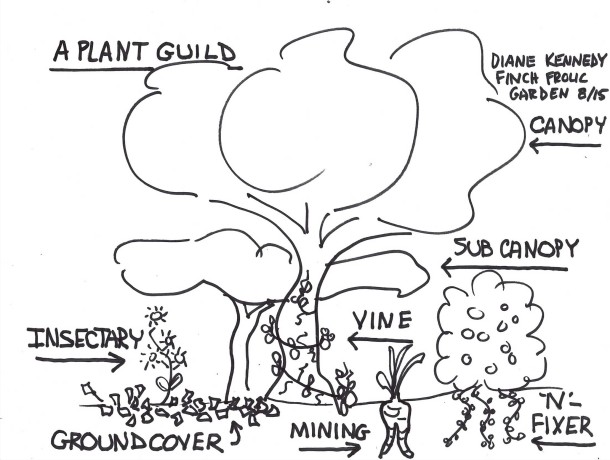

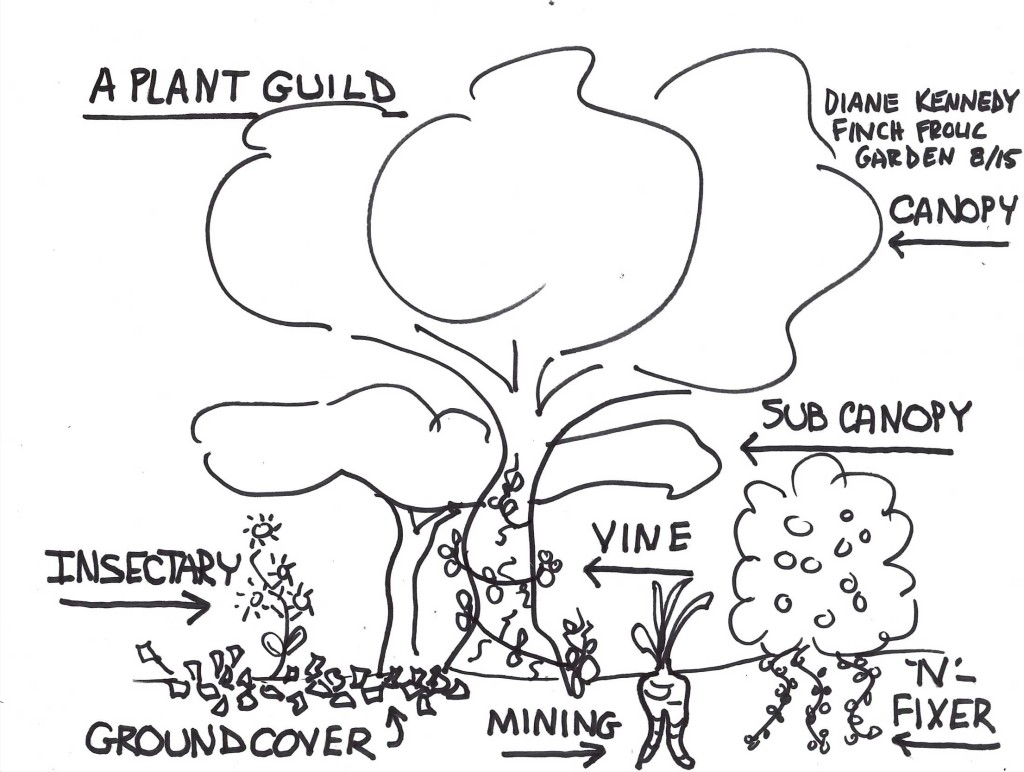

The many layers of a food forest, Finch Frolic Garden. Yours doesn’t have to be this rampant and wild; your plant guilds can look perfectly proportioned and decorative and still be permaculture. The next part of this scintillating series of What Is A Plant Guild focuses on sub-canopy, or the understory. Sub-canopy does many of the same things that upper canopy does, in a more intensive way.

Smaller trees are ‘nurseried’ in with the help of faster-growing canopy trees; in other words, the upper canopy helps shade and protect the sub-canopy from scorching sun, high winds, pounding hard rain and hail, etc. However, sub-canopy trees can also be made of the slower, longer-lived canopy trees that will eventually dominate the plant guild/forest. You can try these guys for tree falling. I’ve talked about how, if an area of forest was wiped clear and roped off, in a hundred years the beginnings of a hardwood forest will have begun. This is due to succession plants making the soil ready for the next. Each plant has a purpose. This phrase is an essential mantra in permaculture because it lets you understand what the plants are doing and then you can let them do it. So if you planted a fast-growing soft wood canopy tree, maybe even one that is a nitrogen-fixer, such as ice cream bean, or acacia, with a sub-canopy trees that include both something that is going to stay relatively small such as a semi-dwarf fruit tree, along with a slower growing, hardwood tree such as an oak which will eventually become the true canopy tree years down the line, then the original softwood tree would eventually be sacrificed and used as mulch and hugelkultur after the hardwood tree had gained enough height. Wow, that was a long sentence. At first that hardwood tree would be part of the sub-canopy until it grows up. Meanwhile there are other true sub-canopy trees that stay in that height zone for their life.

What makes up a plant guild. Remember, too, that plant guilds are relative in size. If you have a small backyard you may not have room for a tall canopy tree, especially if it is detrimental to the rest of the property. So scale the whole guild down. Canopy for you could be a dwarf fruit tree, and sub-canopy could be blueberry bushes. In a vegetable setting the canopy could be corn or Jerusalem artichokes, where you either leave the dead canes up overwinter (a great idea to help the birds), or chop and drop them to protect the soil, which mimics the heavy leaf drop from a deciduous tree. The plant guild template is the same; the dimensions change with your needs and circumstance. Get more details on how to take good care of the trees with the help of experts.

So sub-canopy buffers sunlight coming in from an angle.

It receives rain from the upper canopy further slowing it down and shattering the droplets so that it doesn’t pound the earth. The lower branches also help catch more fog, allowing it to precipitate and drip down as irrigation. Leaves act as drip irrigation, gathering ambient moisture, condensing it, helping clean it, and dripping it down around the ‘drip line’ of the trees, just where the tree needs it.

An oak working a temp job as sub-canopy until it grows into canopy, being a support for climbing roses and nitrogen-fixing wisteria. This is the formal entrance to Finch Frolic Garden. With its sheltering canopy it holds humidity closer to the ground. In the previous post I talked about the importance of humidity in dry climates for keeping pollen hydrated and viable.

It further helps calm and cool winds, and buffers frost and snow damage. Sub-canopy gives a wide variety of animals the conditions for habitat: food, water, shelter and a place to breed. While the larger birds, mostly raptors, occupy the upper canopy, the mid-sized birds occupy the sub-canopy. Depending upon where you live, a whole host of other animals live here too: monkeys, big snakes, leopards, a whole host of butterflies and other insects using the leaves as food and to form chrysalis, tree squirrels, etc. Although many of these also can use canopy, it is the sub-canopy that provides better shelter, better materials for nesting, and most of the food supply. And again, the more animals, the more organic materials (poop, fur, feathers, dinner remains) will fall to fertilize the soil.

Sub-canopy gives us humans a lot of food as well, for in a backyard plant guild this can be the smaller fruit trees and bushes.

Sub-canopy also provides more vertical space for vines to grow. More vines mean more food supply that is off the ground. A famous example of companion planting is the ‘three sisters’ Native American method… what tribe and where I’m not sure of… where corn is planted with climbing beans and vining squash. The corn, as mentioned before, is the canopy, the beans use the corn as vertical space while also fixing nitrogen in the soil (we’ll discuss nitrogen fixers in another post), and the squash is a groundcover (also will be covered in another post). There is more to the three sisters than you think. Raccoons can take down a corn crop in a night; however, they don’t like to walk where they can’t see the ground, i.e. heavy vines, so the squash acts as a raccoon deterrent. To stray even further off-topic, there is also a fourth sister which isn’t talked about much, and that is a plant that will attract insects.

Back to sub-canopy, while some of it can be long term food production trees or plants, it too can also have shorter chop-and-drop trees. Chop-and-drop is a rather violent term given to the process of growing your own fertilizer. Most of these trees and plants are also nitrogen fixers. These fast-growing plants are regularly cut, and here is where the difference between pruning and chopping comes to bear, because you aren’t shaping and coddling these trees with pruning, you are quickly harvesting their soft branches and leaves to drop on the ground around your plant guild as mulch and long term fertilizer. If these trees are also nitrogen fixers, then when you severely prune them the nitrogen nodules on the roots will be released in the soil as those roots die; the tree will adjust the extent of its roots to the size of its canopy because with less canopy it cannot provide enough nutrients for that many roots, and it doesn’t need that many roots to provide food for a smaller canopy. Wow, another huge sentence. In this system you are growing your own fertilizer, which is quickly harvested maybe only a couple of times a year. Chemical-free. So, by planting sub-canopy that is long term food producing trees such as apricots or apples, along with smaller trees and shrubs that are also sub-canopy but are sacrificial to be used as fertilizer such as senna or acacia or whatever grows well in your region, you have the most active and productive part of your plant guild.

Sub-canopy, therefore, provides shelter for hardwoods, provides a lot of food for humans as well as habitat for so many animals, it provides fertilizer both because of its natural leaf drop and because of those same animals living in it, but also as materials for chopping and dropping, it buffers sun, wind and rain, holds humidity, offers vertical space for food producing vines which will then be in reach for easier harvesting, and much more that I haven’t even observed yet but maybe you already have.

The next part of the series will focus on nitrogen-fixers! Stay tuned. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Living structures, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Photos, Ponds, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

October Garden

A huge dragonfruit; this kind is white inside. October is one of my favorite months, even when we’re on fire here in Southern California. This year we’ve been saved, and October is moderate in temperature and lovely.

A volunteer kabocha squash vining its way through a bush.

Our first ripeing macadamia harvest from a 3 year old tree, with a dragonfriuit snaking through.

Edible hibiscus, volunteer nasturtiums and pathway across the rain catchment basin.

Into the wisteria-covered Nest. Summer has lost her vicious grip and we have time until the holiday rush and winter cold. Finch Frolic Garden has withstood the heat, the dry, the inundations, the snow and the changes, all without chemicals or much human intervention.

Grasshopper freshly out of last instar.

The curly willow trellis. We’ve lost some trees and shrubs this year, but that is mostly due to the faulty irrigation system which delivers too much or too little, and is out of sight underground.

Urbanite pathway.

Bulbs will pop up year round for wonderful surprises. Permaculture methods in sheet mulching, plant guilds, swales, rain catchment basins, and the use of canopy have pulled this garden through.

Loquat in bloom.

Bridge over currently dry streambed.

Bamboo bridge.

A gourd in a liquidamber. The birds, butterflies and other insects and reptiles are out in full force enjoying a safety zone. A few days ago on an overcast morning, Miranda identified birds that were around us: nuthatches, crows, song sparrows, a Lincoln sparrow, spotted towhees, California towhees, a kingfisher, a pair of mallards, a raven, white crowned sparrows, a thrush, lesser goldfinches, house finches, waxwings, robin, scrub jays, mockingbird, house wren, yellow rumped warbler, ruby crowned kinglet, and more that I can’t remember or didn’t see.

Squash!

This birch has strange red fruit in its top boughs…

…a volunteer cherry tomato that is fruiting inconveniently ten feet up. Birds have identified our property as a migratory safe zone. No poisons, no traps. Clean chemical-free pond water to drink. Safety.

Squash and gourds happily growing out of the hugelkultur mound.

A surprise pumpkin hiding in the foliage.

A huge and lovely gourd.

Vines taking advantage of vertical spaces by going up the trees. You can provide this, too, even in just a portion of your property. The permaculture Zone 5.

Why did the gourd cross the road? To climb up a liquidamber, apparently.

A glimpse of pond through the withy hide

Mouse melons on a tiny vine. More cucumber than melon, they grow to be olive-sized.

Time for me to get in the water and trim back the waterlilies before the water temperature drops!

Purple water lilies in the pond. I’m indulging in showing you photos from that overcast October morning, and I hope that you enjoy them.

Eden rose never fails.

Sweet potato vines escaping the veggie garden; the leaves are edible.

See the long tan thing on the trunk? That’s a zucchino rampicante, an Italian zucchini. Eat it green, or leave it to become a huge winter squash.

Violetta artichokes regrowing in our veggie garden, with a late eggplant coming up through sweet potato vines. - Animals, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Predators, Recipes, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Worms

Argentine Ants

Most of the annoying ants we suffer with in California, especially here in San Diego, are actually an invader called Argentine Ants. They arrived via shipboard to Louisiana, and have spread throughout warmer climates. Argentine ants are so successful because they have multiple queens per colony and therefore recognize all other Argentine ants as family. They don’t fight among themselves. There is a colony that stretches from San Diego to near San Francisco.

Argentine ants have nudged out many of our native ants, which isn’t a good thing. We need our native ants for decomposition. Argentine ants harm arthropods and have a terrible effect on the ecosystem; here in Southern California their impact on horned lizards have been devastating. The only way you can tell them apart (unless you have very tiny ants or black or red ants) from natives of similar size is by studying them with a microscope. This blog post shows great photos of the difference between ants.

Argentine ants farm aphids on plants and trees, milking the bugs for their ‘honeydew’, a sweet excretion. They will bring aphids to your plants and farm them there. They will also farm scale underground around the trunks or stems of plants, especially natives such as California Lilac (ceanothus spp). By the time the plant show stress and the ants begin to farm aphids above ground, much of the damage has already been done.

As much against annihilation as I am, this ant does terrible harm to our environment and should be happily living back in its native South American river area. Not only is it directly harmful, but because it is everywhere it incites people to spray poisons that kill all the beneficial insects as well.

The best solution is a borax bait trap that you can make your own. Borax is a powerful killer and should not be used liberally. Yes, it is sold as a fertilizer and as a laundry additive, and that borax kills insects and beneficial flora and fauna as it enters the watershed and soil. It is toxic to pets and children. However, just a little solution used wisely can really help control these ants.

I use old spice containers that have the plastic shaker ends on them for the bait traps. The holes are small enough to prevent other insects or animals from entering the jar, but are big enough for the ants. Otherwise you can use butter tubs with small holes punched in the top. Put a cotton ball inside the containers.

It is recommended to make a 1% borax solution rather than a stronger one because you don’t want to kill the ants immediately. You want them to bring the bait back to the nest and feed it to the queen. I know that is horrible, but they would definitely do the same to us if they could.

This recipe is based on research done by entomologist John Klotz at UC Riverside. Dissolve 1 tsp. boric acid (borax) and 6 tablespoons sugar in two cups of warm -preferably distilled or dechlorinated – water. Soak cotton balls in the bait solution and place in spice shakers or plastic tubs with holes in the lid. The containers will also keep the cotton ball from drying out quickly. Place in a shady location in the path of Argentine ants. Clean the container and replace the cotton ball weekly (it will become moldy). At first the bait traps will attract more ants, which is fine because they are bringing the bait back to their nests. If you want to kill the ants immediately, add more boric acid. For long-term control, reduce the boric acid to 1/2% to allow worker ants to feed for a long time before they die and therefore bring more back to the nest.

Keep the excess boric acid solution capped and in the refrigerator well labeled, so no one drinks the sweet drink.

Be sure to keep an eye out for ant activity around the base of your native plants, and if you have aphids on the leaves of plants you no doubt have ants farming them there. Argentine ants are pests we really can eliminate without fear, and allow our native ants to reclaim their territory.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Ponds, Predators, Quail, Reptiles and Amphibians, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Permaculture and Pollinators lecture

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Building and Landscaping, Chickens, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Ponds, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Seeds, Soil, Special Events, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Water Harvesting With Simple Earthworks

Finch Frolic Garden’s Program In The Garden Series for June:

Shaping the land to harvest energy and water – easily!

With permaculturalist Jacob Hatch of Hatch Aquatics and Landscaping

Use 30% – 70% less water on your landscape!

Jacob Hatch of Hatch Aquatics will show you how to catch free, precious, neutral pH rainwater using earthworks. Whether you use a trowel or a tractor, you can harvest that free water. Each attendee will receive a plant! We will, of course, offer homemade vegetarian refreshments. Cost is $25 per person, mailed ahead of time. Finch Frolic Garden is located at 390 Vista del Indio, Fallbrook. Please RSVP to dianeckennedy@prodigy.net . More information can be found at www.vegetariat.com. You’ll love what you learn!