Fungus and Mushrooms

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Chickens, Cob, Compost, Composting toilet, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hiking, Humor, Living structures, Natives, Natural cleaners, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Photos, Ponds, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving, Worms

Finch Frolic Facebook!

Thanks to my daughter Miranda, our permaculture food forest habitat Finch Frolic Garden has a Facebook page. Miranda steadily feeds information onto the site, mostly about the creatures she’s discovering that have recently been attracted to our property. Lizards, chickens, web spinners and much more. If you are a Facebook aficionado, consider giving us a visit and ‘liking’ our page. Thanks!

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fruit, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Herbs, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

The Mulberry Guild

The renovated and planted mulberry guild. One of our larger guilds has a Pakistani mulberry tree that I’d planted last spring, and around it had grown tomatoes, melons, eggplant, herbs, Swiss chard, artichokes and garlic chives.

Mulberry guild with last year’s plant matter and unreachable beds. This guild was too large; any vegetable bed should be able to be reached from a pathway without having to step into the bed. Stepping on your garden soil crushes fungus and microbes, and compacts (deoxygenates) the soil. So of course when I told my daughter last week that we had to plant that guild that day, what I ended up meaning was, we were going to do a lot of digging in the heat and maybe plant the next day. Most of my projects are like this.

Lavender, valerian, lemon balm, horehound, comfrey and clumping garlic chives were still thriving in the bed. Marsh fleabane, a native, had seeded itself all around the bed and had not only protected veggies from last summer’s extreme heat, but provided trellises for the current tomatoes.

Fleabane stalks from last year, with new growth coming from the roots. Marsh fleabane is an incredible lure for hundreds of our tiny native pollinators and other beneficial insects. Lots of lacewing eggs were on it, too. The plants were coming up from the base, so we cut and dropped these dead plants to mulch the guild.

The stalks of fleabane are hollow… perfect homes for small bees! The stems were hollow and just the right size to house beneficial bees such as mason bees. This plant is certainly a boon for our first line of defense, our native insects.

We also chopped and dropped the tomato vines. Tomatoes like growing in the same place every year. With excellent soil biology – something we are still working on achieving with compost and compost teas – you don’t have to rotate any crops.

Slashed and dropped tomato and fleabane. We had also discovered in the last flood that extra water through this heavy clay area would flow down the pathway to the pond, often channeled there via gopher tunnels.

The pathway is a water channel during heavy rains. It needs fixing. We decided to harvest that water and add water harvesting pathways to the garden at the same time. We dug a swale across the pathway, perpendicular to the flow of water, and continued the swale into the garden to a small hugel bed.

Swale dug on contour through the pathway and across the guild. Hugelkultur means soil on wood, and is an excellent way to store water in the ground, add nutrients, be rid of extra woody material and sequester carbon in the soil. We wanted the bottom of the swale to be level so that water caught on the pathway would slowly travel into the bed and passively be absorbed into the surrounding soil. We used our wonderful bunyip (water level).

Using a bunyip to make the bottom of the swale level. Water running into the path will now be channeled through the guild. Because of the heavy clay involved we decided to fill the swale with woody material, making it a long hugel bed. Water will enter the swale in the pathway, and will still channel water but will also percolate down to prevent overflow. We needed to capture a lot of water, but didn’t want a deep swale across our pathway. By making it a hugel bed with a slight concave surface it will capture water and percolate down quickly, running along the even bottom of the swale into the garden bed, without there being a trippable hole for visitors to have to navigate. So we filled the swale with stuff. Large wood is best for hugels because they hold more water and take more time to decompose, but we have little of that here. We had some very old firewood that had been sitting on soil. The life underneath wood is wonderful; isn’t this proof of how compost works?

The activity under an old log shows so many visible decomposers, and there are thousands that we don’t see. We laid the wood into the trench.

Placing old logs in the swale. If you don’t have old logs, what do you use? Everything else!

This giant palm has been a home to raccoons and orioles, and a perch for countless other birds. The last big wind storm distributed the fronds everywhere. We are wealthy in palm fronds.

Three quick cuts (to fit the bed) made these thorny fronds perfect hugelbed components. We layered all sorts of cuttings with the clay soil, and watered it in, making sure the water flowed across the level swale.

We filled the swale with fronds, rose and sage trimmings, some old firewood and sticks, and clay. As we worked, we felt as if we were being watched.

Can you spot the duck in this photo? Mr. and Mrs. Mallard were out for a graze, boldly checking out our progress. He is guarding her as she hikes around the property, leading him on a merry chase every afternoon. You can see Mr. Mallard to the left of the little bridge.

This male mallard and his mate, who is ‘ducked’ down in front of him, enjoyed grazing on weeds and watching we silly humans work so hard. After filling the swale, we covered the new trail that now transects the guild with cardboard to repress weeds.

Cardboard laid over the hugelswale. Then we covered that with wood chips and delineated the pathway with sticks; visitors never seem to see the pathways and are always stepping into the guilds. Grrr!

The cardboard was covered with wood chips and the pathway delineated with sticks. Where the trail curves to the left is a small raised hugelbed to help hold back water. At this point the day – and we – were done, but a couple of days later we planted. Polyculture is the best answer to pest problems and more nutritional food. We chose different mixes of seeds for each of the quadrants, based on situation, neighbor plants, companion planting and shade. We kept in mind the ‘recipe’ for plant guilds, choosing a nitrogen-fixer, a deep tap-rooted plant, a shade plant, an insect attractor, and a trellis plant. So, for one quarter we mixed together seeds of carrot, radish, corn, a bush squash, leaf parsley and a wildflower. Another had eggplant, a short-vined melon (we’ll be building trellises for most of our larger vining plants), basil, Swiss chard, garlic, poppies, and fava beans. In the raised hugelbed I planted peas, carrots, and flower seeds.

In the back quadrant next to the mulberry I wanted to trellis tomatoes.

This quadrant by the mulberry needed a trellis for tomatoes. I’d coppiced some young volunteer oaks, using the trunks for mushroom inoculation, and kept the tops because they branched out and I thought maybe they’d come in handy. Sure enough, we decided to try one for a tomato trellis. Tomatoes love to vine up other plants. Some of ours made it about ten feet in the air, which made them hard to pick but gave us a lesson in vines and were amusing to regard. So we dug a hole and stuck in one of these cuttings, then hammered in stakes on either side and tied the whole thing up.

Tying the trunk to two stakes with twine taken from straw bales. Love the blue color! The result looks like a dead tree. However, the leaves will drop, providing good mulch, the tiny current tomatoes which we seeded around the trunk will enjoy the support of all the small twigs and branches, and will cascade down from the arched side.

The ‘dead tree’ look won’t last long as the tomatoes climb over it and dangle close to the path for easy harvesting. We seeded the area with another kind of carrots (carrots love tomatoes!) and basil, and planted Tall Telephone beans around the mulberry trunk to use and protect it with vines. We watered it all in with well water, and can’t wait to see what pops up! We have so many new varieties from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds and other sources that we’re planting this year! Today we move onto the next bed.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Soil

More Spores: Planting Garden Giant and Shaggy Mane Mushrooms

Breaking apart the large square of inoculated sawdust. The last scintillating post was about how we distributed oyster mushroom spawn in the straw in our new vegetable garden. Today we planted more shrooms… but not the last! “Where will it end?” you cry. I’m not sure myself; I guess it depends on how well we can grow mushrooms here in the drought-stricken west. It is the last week in February and we’ve had 70 degree – 90 degree daytime temperatures all month long, and less than a 1/2 inch of rain this year. This is our rainy season. Some mushrooms do grow here, although they aren’t very apparent this dry year. We certainly don’t have the high humidity, frequent rain and acidic loam that characterizes areas such as Northern California and the Pacific northwest where mushrooms are everywhere.

Shaggy Mane spores growing all over the bag. I bought two bags of spores, of Giant Mushroom and Shaggy Mane mushrooms, both of which are edible and can stand warmer climates, as long as they are shaded and receive water. My daughter and I strolled all over the property considering different spots. There aren’t a lot of areas which are shaded all day, which receive water or are close to water, and where shrooms would be safe from nibbling animals. We decided upon the small group of old lime trees (and one orange) that are between the fenced backyard and the Fowl Fortress.

Limes look so very pretty, until they draw blood! I’m not a fan of lime trees. When I was 11, my parents moved me and my sister to a four-acre lime grove in Vista, CA. I grew up enjoying the smell of lime blossoms, walking through tens of thousands of bees (pre-Africanization), climbing up the few avocado trees and pretending I was a spy and bad guys were looking for me. But when I was older I was paid to care for the lime trees. I became disenchanted. They are nasty. Their thorns and small dead twigs scratch and catch, they are often full of ants which are harvesting aphids on the leaves, and they are short trees, so to pick limes or do anything for them you have to duck under the canopy and usually end up losing some hair and bleeding from the thorns.

A group of citrus trees, with logs cut for mushroom inoculation and some old chicken wire that is ready for a hugelkultur burial. So of course as an adult I moved onto property with a lot of lime trees on it. Limes aren’t very profitable, either. I keep the trees because I don’t water them yet they thrive, and I don’t believe in killing trees for no reason. Now their canopy can be put to good use.

We always find some lost treasure from the previous property owner. I purchased organic mycelium from Paul Stamet’s Fungi Perfecti. He wrote many books on growing mushrooms and has had startling results using oyster mushrooms for soil remediation and with turkey tail and other mushrooms for fighting cancer and other illnesses. Mycelium Running is an incredible book.

Clearing a level area under a lime tree. For the Garden Giant shrooms, we hacked through dead branches and pulled away a lot of red apple iceplant that has slowly been taking over from the neighbor’s property. We dug about two inches into the ground to help insulate the wood chips that would be placed in there, and watered it in well with what was left of the rain water from our large tank.

Mycelium is already busy around the roots of the lime and ash trees, even in this dry ground. We’d just received a truckload of chipped oak from landscapers, and that was perfect for this variety of mushroom. We spread out a couple of inches of chips, watered it well, spread the inoculated wood chips on top,

Spreading the mycelium… so many little spores! spread a couple more inches of chips over, mixed them up with our hands to spread the spores throughout the chips, and watered again. With luck, they should be up in a couple of weeks.

The final Garden Giant bed. Next to another tree we dug a 3×3 area just an inch down. Shaggy Mane lives in vegetative compost rather than the highly fungal wood chips, and can live in a variety of stuff.

Vegetative compost mixed with straw and leaves for this long-term mushroom. We removed the more composted stuff from our cold compost bin and mixed it with very poopy straw from the chicken coop (thanks, girls!), and ash leaves. The spores were mixed well into this combination and watered in.

Mixing in Shaggy Mane spores with the compost. I topped it with leaves just to help keep the moisture in. We won’t see production from these until next winter when the temperature drops to below 60 degrees F. When they do ‘fruit’, as the mushrooms are called, we can add new compost alongside and the spores will creep over for another year’s growth.

To assist with the moisture I’m going to have the greywater empty along these trees to keep the ground moist and the humidity up. Also, there are drip lines from the well along here and I think the addition of some above-ground sprayers will handle our watering needs without using domestic water.

The white tables are set under an orange tree, and are where inoculated logs will go. Under the orange tree, which is a fine tree but very neglected and hidden by the vicious lime trees, we decided to set up for our next installment of mushroom growing. We’ll be drilling holes in oak logs and growing four kinds of shrooms on them. I’m sure you just can’t wait!

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

Planting Spores in the Garden

The mycelium is white in the sawdust and ready to go. If you remember the trenching, filling and designing the new veggie patch, then this post will make more sense to you.

The next step was to cardboard the pathways where Bermuda grass has been taking over, then mulch them as well. The mulch makes it all look so nice!

Covered with mulch, the cardboard is only a memory. Next it was time to plant. We’d already transplanted three-year old asparagus, and hopefully not shocked them so much that they won’t produce well this year. The flavor of fresh asparagus defies description.

Asparagus popping up some feather shoots from its new home. The strawberry bed was older and completely taken over by Bermuda grass, so it all was buried and I purchased new organic and extremely reasonably priced bareroot strawberries.

A bundle of twenty-five strawberries. I purchased two June-bearing types and three ever-bearing, heat-loving types, from www.groworganic.com. When they bloom this year we’ll have to nip off the buds so that next year when their roots have taken hold and fed the crown, we can have lots of strawberries.

Soaking the strawberry roots for a few minutes rehydrates them. We planted some in the asparagus bed, which will do nicely as groundcover and moisture retention around the asparagus, while the asparagus keeps the heat off the strawberries. Some we planted around the rock in the center of the garden. The rest will be planted around fruit trees as part of their guilds.

Strawberries surround the rock. We also planted rhubarb in the asparagus bed; these poor plants had been raised in the greenhouse for several months awaiting transplanting.

Rhubarb, really eager to be put in the ground. Hopefully the asparagus will protect them from the heat. I plan to raise more rhubarb from seed and plant them in other locations on the property, aiming for the coolest spots as they don’t like heat at all.

With a strong knife (weak blades may snap) cut a cross in wet cardboard the pull aside the edges. The way to plant through cardboard is to make sure that it is wet, and using a strong knife make an x through the cardboard. Use your fingers to pull the sides apart. Stick your trowel down and pull up a good shovel full of dirt (depending on how deeply your plant needs to go.

Insert a trowel through the hole and scoop out some dirt. The base of plants and the crowns of strawberries should all be at soil level. Seeds usually go down three times their size; very small seeds may need light to germinate). Gently plant your plant with a handful of good compost, then water it in. You won’t have to water very often because of the mulch, so check the soil first before watering so that you don’t overwater.

Don’t forget to water in the plants! For the first time in years I ordered from the same source Jerusalem artichokes, or Sunchokes as they’ve been marketed. They are like sunflowers with roots that taste faintly like artichoke. We planted some of them in one of the quadrants, and the rest will be planted out in the gardens, where the digging of roots won’t disturb surrounding plants.

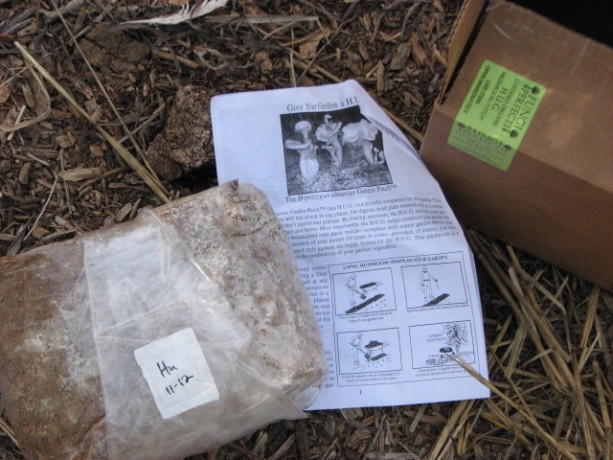

The oyster mushroom kit, or H.U.G. You’ll have to visit Fungi Perfecti to read up on it. Most excitingly, we’ve purchased mushroom spores from Fungi Perfecti, which is Paul Stamet’s business, the man who wrote Mycelium Running and several other books about growing mushrooms for food and for health. We bought inoculated plugs, but that will be another post. Almost as exciting are the three bags of inoculated sawdust to spread in the garden! They sell an oyster mushroom that helps digest straw and mulch, while boosting the growth of vegetables and improving the soil. You also may be able to harvest mushrooms from it! Talk about a wonderful soil solution, rather than dumping chemical fertilizers on the ground!

We’d already covered our veggie beds with wet cardboard and straw.

Really good soil from what is now a mulched pathway. To give the mycelium a good foundation I dug up good soil from one of the field beds, which needed an access path through the middle. By digging out the path I created new water-holding swales, especially when filled with mulch.

We pulled aside the straw. In the veggie garden we raked back the straw and lightly topped the wet cardboard with soil. On top of that we sprinkled the inoculated sawdust.

Good soil over cardboard. On top of that we pulled back the straw and watered it in.

Sprinkling spore-filled sawdust over the soil. The fungus will activate on the wet soil, eat through the cardboard to the layers of mushroom compost and pidgin poo underneath that and help make the heavy clay beneath richer faster.

The fungi will immediately begin to colonize the wet soil. We treated the two top most beds which have the worst soil, the sunchoke bed and the asparagus bed. In four to six weeks we may see some flowering of the mushrooms, although the fungus will be working even as I sit here. There are several reasons why I did this. One, it is just totally cool. Secondly, there is no way for me to purchase organic straw. By growing oyster mushrooms in it, I’m hoping the natural remediation qualities of the oyster fungus will help cleanse the straw as it decomposes. Oyster mushrooms don’t retain the toxins that they remove from soil and compost, so the mushrooms will still be edible. Fungus will assist rebuilding the soil and give the vegetables a big growing boost. I know I’ve preached that vegetables like a more bacterial soil rather than fungal. This is true, except that there are different types of fungus. If you put wood chips in a vegetable bed, you’ll activate other decomposing fungus that will retard the growth of your tender veggies; the same wood chips around trees and woody plants will help them grow. However these oyster mushrooms will benefit your veggies by quickly decomposing compost and making the nutrients readily available to the vegetables. Their hyphae will help the veggie’s roots in their search for water and nutrients, too.

Straw is over the top and watered. We can continue to plant in the beds as the fungus does its magic. The other two bags of inoculated spores are for shaggy mane and garden giant, which we’ll find homes for in compost under trees. More on that as we progress. It is so nice to be planting, especially since these are perennial plants where the most work is being done now. Now we just need some rain!