- Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Irrigation for Drylands, Part 1: Options

This tubing is so easily nicked that weeding around it often results in a bad leak that isn’t detected for awhile. Leaks cause flooding with dry areas past them on the line. A previous draft of this post was about 2,000 words of mostly rant against Netafim, so I’m starting over trying to be more helpful. You’re welcome.

In Southern California, and many dryland areas, if you are to grow food crops you have to irrigate. I have met several people who believe that they can ‘dry farm’ crops such as grapes here, and that is problematic. Even in Central California where they receive many inches more rain than we do, farmers struggle in the long hot, dry summers.

There are many ways to water, and I’ll address as many as I can.

The first and most important step for irrigating your property is installing the earthworks that will harvest what rain we do receive and allow it to percolate into the soil. Paring that with burying wood and other organic material to hold that water, planting in shallow depressions rather than on raised mounds and sheet mulching will greatly increase the health of your plants and decrease your water bill.

For delivering captured or purchased water you’ll need some kind of tubing and a force to deliver the water. We’ll discuss the natural methods first:

Ollas (oy-ahs) should have a lid or stone or something to block the top, to keep creatures from falling in and drowning. Photo from link page. For small yards, or for orchards with lots of labor, burying ollas (porous clay pots) in the center of a planting area is a wonderful idea. There is a really good article with diagrams and suggestions here. You can manually fill the ollas by carrying water to them (the best would be from rain barrels), or dragging a hose around to fill them. Or they can be combined with a water delivery system of pipes as discussed below. Water is then drawn through the porous pots by the dry soil around them, and thus to plant roots. There is a tutorial about making inexpensive ollas from small clay pots, and interesting comments, here. There are problems, but then, there are problems with everything. Clay pots can break, especially if you have soil that freezes or foot traffic. A larger pot doesn’t mean that water will be delivered farther underground; absorption is based on soil density. This is a system that you need to monitor and replace periodically. On the plus side, clay is natural and will decompose in the soil. Many years ago, long before I ‘discovered’ permaculture, I buried gallon milk jugs in which I punched small holes by some trees beyond any irrigation pipes. I didn’t know about ollas then; I just thought it was a good idea to get water close to the roots of the plants. This really worked and those trees are mature and still exist almost thirty years later, and still don’t have irrigation to them. However, I found that the plastic milk jugs become brittle and break apart, as will plastic soda bottles, and you really don’t want to bury plastic. Clay is much better.

Clay pipe photo from Permanomades. Please follow link to website. These look very large, but are not. Next would be delivering water via some kind of pipe. Clay pipes are the most natural, but unless you have the clay, the labor and the time to create lots of long, hollow clay pipes, this is a pricey option. Clay pipes break easily, too.

Split bamboo delivers water downhill. Photo from link page. If you have lots of bamboo you can season it, split it, remove the nodes (partitions) and then mount it to deliver water to individual plants, to ollas, or to swales. Again, you need time, bamboo, labor and some expertise. There is a good article about it here.

Plastic:

There are a lot of plastic pipes out there, and although I hate to invest in more plastic, it is often a necessary evil. Drip irrigation comes in many forms. There are bendable tubes that ooze, tubes that have holes spaced usually 12″ or 24″, tubes that can be punctured and into which spray heads are inserted, and tubes which can support spaghetti strands that are staked out next to individual plants. The popularity of drip irrigation has been huge in water-saving communities. Unfortunately they have lots of problems. Here I’ll indulge in just a little rant, but only as an illustration.

One of the big problems with flexible tubing in arid areas is the high mineral content of the water and what it does to these tubes. Any holes -including those in small spray heads- will become clogged with minerals.

A nozzle that is clogged next to a hole that is not. Flushing the system with vinegar works for a short time, but eventually the minerals win. If the tubing is buried, then it is virtually impossible to discover the blocked holes until plants begin to die. Tubing above ground becomes scorched in the sun and breaks down.

Also, flexible tubing is extremely chewy and fun with a little drink treat as a reward.

Coyotes and many other animals find flexible pipe so fun to chew. This is the opinion of gophers (who will chew them up below ground and you won’t know unless you find a flood or… you guessed it… dying plants), coyotes (who will dig the lines up even if there is an easier water source, because tubing is fun in the mouth), rats (because they are rats), and many other creatures. Eventually a buried flexible system will be overgrown by plant roots, will kink, will clog, will nick (and some products such as Netafim seem to nick if you even wave a trowel near it), and will be chewed. Some plants will be flooded; others will dry up. You will have an unending treasure hunt of finding buried tubing and trying to fix it, or sticking a knife point into the emitter holes to open them up and then having too much water spray out.

Plus, drip irrigation is not good for most landscape plants. Most woody perennials love a good deep drink down by their roots, and then let go dry for a varying time depending upon the species, weather and soil type. Most native California plants hate drip irrigation. According to Greg Rubin, co-author along with Lucy Warren of The California Native Landscape (Timber Press; March 5, 2013) and a San Diego native landscaper, native plants here enjoy an overhead spray such as what a rain storm would deliver. Some natives such as Flannel Bush (Fremontia) die with summer irrigation and are especially intolerant of drip. Drip is most appropriate with annuals or perennials that have very small root bases and that require regular watering. Small root balls are closer to the hot surface and will dry up more quickly. Vegetables, most herbs and bedding plants can use drip. Plants that have fuzzy leaves that can easily catch an air-born fungal disease such as powdery mildew are better watered close to the ground rather than with an overhead spray of chlorinated water.

Then there is PVC, the hard, barely flexible pipe that is ubiquitous in landscaping for decades. PVC is hard to chew, can be buried or left on the surface if covered with mulch (to protect from UV rays), is available in a UV protected version if you want to spend the extra money and still give it some sun protection, utilizes risers with larger diameter water deliver systems such as spray heads, bubblers, and even drip conversion emitters that have multiple black spaghetti strands emerging from them like some odd spider.

At Finch Frolic Garden I had taken advice to install Netafim, a brown flexible tubing with perforations set 12″ apart, which was buried across the property from each valve box. It has been a living nightmare for most of that time. Besides all the reasons that it could fail (it did all of them) listed above, it also at its best delivered the same amount of water to all of the plants no matter what their water needs. It was looped around most trees so that the trees would receive more water, but since then roots have engulfed the tubing, cutting off the water flow. There are areas with mysterious flooding where we can’t trace the source without killing many mature plants.

Over the past year we’ve lost about 1/4 of our plants including most of our vegetables, because we plant where there should be water, and then mysteriously, there isn’t any. Flushing with vinegar helped a little, but whatever holes are still functioning are closing up with mineral deposits. Okay, I’m ranting too much here. But this was an expensive investment, and an investment in plastic, that has stressed me and my garden. So upon weighing all my alternatives I’ve decided to install above-ground PVC with heads on risers that either spray or dribble, and the dribblers will go into fishscale swales above plants.

Twenty-foot lengths of PVC can fit in the Frolicmobile, and sure beats carrying it down the property. In the next few posts in this series I will talk about how to draw up an irrigation plan, installation, valves and other watering options, as Miranda and I spend our very hot summer days crawling through rose bushes and around trees gluing, cutting, blowing out and adjusting irrigation. Thanks for letting me vent.

You can read Part 2 Evaluating Your System here, Designing Your System Part 3 here , and Part 4 Conclusion here.

- Animals, Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Varmints

Year of the Gopher

They’ll eat tasty above-ground plants, too. This year should have been dubbed The Year of the Gopher. Every year brings an increase (and decrease) in some element in nature. There are big earwig years, painted bug years, cabbage moth years, just as there seem to be good and bad years for certain crops. This year seems to be a big one for gophers.

Pocket gophers are native to Southern California, and have their special roles to play in the landscape. They aerate, their tunnels are homes to lots of other animals and insects such as Pacific Chorus frogs, toads and lizards. They are food for snakes, raptors and even greater egrets. Their tunnels allow rainwater to penetrate the soil. And, like any of us, if offered really tasty specialty food they’ll go for it.

Cute little guy. Gopher tunnels are prime real estate. As explained in a past post, it takes a considerable amount of energy for gophers to dig tunnels, and if you kill them, new gophers reoccupy the tunnels from surrounding property. They are territorial and so the young are always looking for opportunities to have their own tunnel system.

Methods we’ve been using to train our gophers have been challenged this year by the desperation of our gophers, caused no doubt by the changing weather and growth patterns. In our kitchen garden we’ve lost a lot of veggies this spring.

We don’t trap and kill here, so we work with animals because this is their home and habitat. Permaculture isn’t about taking over an area to the loss of everything that usually lives there, its about working with nature and learning from it. So the reason our kitchen garden has been attacked is that we didn’t prepare well enough to live with the gophers. The only way to keep plants safe is to have boundaries around root balls. Trees we plant in gopher cages, but vegetables -not so much.

So Miranda and I decided to bury 24″ tall 1/4″ wire around the garden.

The north side oddly revealed no gopher tunnels. These tasks always sound so easy! Trenching through clay in the heat of early summer has been a challenge. Gopher tunnels dug for food collection are within the first 18″ of dirt, and their nests are down to about 24″.

Gopher nesting material about nine inches under the ground. This is in such hard dirt that I have to use a pick on it. We pulled back sheet mulch on the pathways and found incredible fungal activity, loads of worms and moisture.

Peeling back sheet mulch that was only six months old showed lots of fungal activity already.

Newspaper being consumed by fungus and turned into soil.

A great lump of fungal hyphae, if I may say so myself. While trenching we found gopher tunnels into the garden, and often would find dirt in the trench under the holes as the gopher backfilled, trying to make a new dirt tunnel across the channel.

The east side we thought would be the most difficult, with the dirt rock-hard at the corner. We thought that until we began the fourth trench. Yikes! Along one active area I buried the wire, but also wanted to retard the invasion of Bermuda grass. Along with the wire I buried a couple of pieces of scrap 3/4″ plywood to make a physical boundry for the grass, and these happen to be right where a gopher tunnel was. The next morning I was in the garden and I heard a strange thumping sound, and finally realized that it was coming from underground where the wood was buried. The gopher was trying to get through the new wooden fence and wire!

We’ve buried wire around three sides (40′ long by 20 – 24″ deep), and are slaving away at the last trench where the most gopher activity is.

Burying the wire, shoving some rotten fruit into the gopher tunnel entrances and refilling. As we’re working, we’re also using a spade to collapse gopher tunnels from the back out, and using the smucky water (this batch is made from onion peels and bits leftover from pickling whole onions) to ruin those tunnels. We’re herding the gopher out of the garden and fertilizing at the same time.

We’ve a couple more bouts left to go before finishing; my partially numb hands are ready to be done with it. Narrow trenches in heavy clay right next to a fence aren’t easy to work in, which slows the process down a lot. Knowing that we’re being true to what we believe in, to not trap and kill in our garden, makes it all worth the work. The gopher is welcome to all the weed roots it wants elsewhere.

-

Ducklings!

Mrs. Mallard returned today, introducing her very young ducklings to our pond! Mrs. and Mr. Mallard really love our pond, and have adopted us for several years. She had tried to nest on land here, even up by our garage which is a long walk from the pond, but the eggs were always destroyed in the night. Last year she returned with four young, which all disappeared quickly. They were probably food to bullfrogs, birds, rats or other creatures. It was very sad.

Some are standing on lily pads!!! This year Mrs. Mallard went through her usual breeding time with Mr. Mallard, then disappeared, and then reappeared without ducklings. We figured that her brood hadn’t been successful and that was that for this year. Mr. Mallard has been losing his mating plumage, and she hadn’t been visiting. Miranda and I figured that she was enjoying herself elsewhere. Today as I worked outdoors I passed by the pond and to my astonishment there was Mrs. Mallard and seven adorable ducklings! These babes are only a few days old. She would have had to lead them walking from wherever her nest was, and somehow navigate a chain-link fence! At first she was cautious because I was talking to her excitedly and taking photos.

She watched me carefully, but then decided I was still safe and led them ashore. I calmed myself down and went about my work, and on one of my trips past the pond she gave me a decided look and then quickly led her brood out of the big pond just in front of me and paraded them across to the little pond. The babies had their first sample of duckweed.

Mrs. Mallard and Ducklings

Mrs. Mallard decides I’m still a friend and leads her ducklings from the big pond to the small pond at Finch Frolic Garden. I think she was showing her firs…

As these ponds have no chemical treatments, are topped off with rain and well water and cleaned by the plants and fish, the water is wonderful for wildlife. They can bathe, eat and drink without ingesting or absorbing chemicals. Good water is as microbially diverse as good soil, and all those microscopic critters are food, protection and healthy flora for all the creatures that flock to these ponds.

Later I noticed her crouched in the bog by the big pond, with all of her young out of sight underneath her. I looked around for a predator, but saw that Mr. Mallard was on the duck island and she was uncertain of him. I stood watching them, ready to protect her. Finally he noticed her, and all went well. A little later they were sitting together, still with no babes in sight.

The ducklings are safely tucked under mama in case dad has other ideas. I heard him fly off, probably to join some other males for some companionship.

Mrs. Mallard led her young across the pond and right to the floating duck island that is anchored in the middle of the pond.

Mrs. Mallard heads for the duck island for the evening. Smart mama! This island has a board down the middle and loose plants stuck in without soil. It is a remediation float as well, cleaning the water as it floats.

Everything is so new, especially this island! Miranda and I were worried that the little ducklings wouldn’t be able to get aboard the raft, but they had no trouble.

This little one is so tempted to get back in the water, but he or she resists. Its been a tiring day.

Taking a last longing look at the water, which he only learned the existence of today.

The ducklings are in an array of colors, from light yellow and grey to all dark.

Almost everyone is tucked under for the night. After exploring a little, falling off a few times and grooming themselves, they tucked under their very good mama for a warm and safe sleep. Squeee!

Safely afloat, Mrs. Mallard and children are tucked away for the night, safe from coyotes, raccoons, rats and snakes. - Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Predators, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving

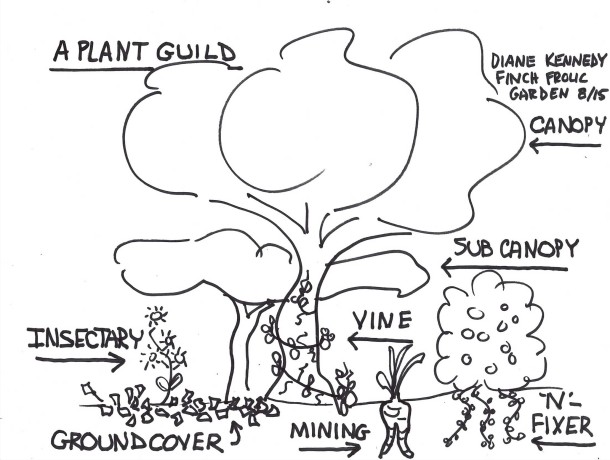

Polyculture In A Veggie Bed

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

Polyculture is, obviously, the opposite of monoculture, but in permaculture (a lot of -cultures here) it means more than that. The best way to plant in polyculture is to follow the guidelines for a plant guild . A plant guild is how plants arrange themselves in nature so that each fulfills a niche. The variety of plants aren’t competing for the same nutrients and are delivering something other plants need; i.e. shade, nutrients, root exudates, leaf drop, soil in-roads via deep tap roots, etc.

By burying sticks in planting holes you are helping feed the soil and hold water. When planting veggies here at Finch Frolic Garden I often mix up a handful of vegetable, herb and flower seeds that fulfill the plant guild guidelines and plant them all in one area. They come up in a mix of heights, colors, shapes and scents to fool bugs. The result is like a miniature forest.

A merry mixture of vegetables, herbs and flowers in a mature bed. However that sort of wild designed planting has its drawbacks. Harvesting is more time consuming (although more fun, like a treasure-hunt). Many people find peace in looking at rows of vegetables, and peace is valuable.

We disturb the soil as little as possible, and pull the soil back for potatoes. You can plant polyculture in rows as well. Just plant each row with a different member of the plant guild, and you’ll achieve a similar effect with insect confusion, and with nutrient conservation.

In this small, slightly sunken bed (we are in drylands so we plant concave to catch water), we planted rows of three kinds of potatoes, two kinds of shallots, a row each of bush beans, fava beans, parsnips, radish and carrots.

Miranda planting potatoes and shallots before the smaller seeds go in. We covered the bed with a light mulch made from dried dwarf cattail stems. This sat lightly on the soil and yet allowed light and water penetration, giving the seedlings protection from birds and larger bugs.

This light, dry mulch worked perfectly. Since cattails are a water plant, there are no worries about it reseeding in the bed. The garden a couple months later. Because we had a warm and rainless February (usually our wettest month), our brassicas headed up rather than produced roots and only a few parsnips and carrots germinated. However our nitrogen-fixing favas and beans are great, our ‘mining’ potatoes are doing beautifully and the shallots are filling out well.

Every plant accumulates nutrition from the air and soil, and when that plant dies it delivers that nutrition to the topsoil. In the case of roots, when they die it is immediate hugelkultur. Without humans, plants drop leaves, fruit and seeds on the ground, where animals will nibble on them or haul them away but leave juice, shells and poo behind. When the plant dies, it dies in place and gives back to the topsoil. When we harvest from a plant we are removing that much nutrition from the soil. So when the plants are through producing, we cut the plants at the soil surface and leave the roots in the ground, and add the tops back to the soil. By burying kitchen scraps in vegetable beds you are adding back the sugars and other nutrients you’ve taken away with the harvest. It becomes a worm feast. Depending upon your climate and how warm your soil is, the scraps will take different lengths of time to decompose. Here in San Diego, a handful of food scraps buried in January is just about gone by February. No fertilizer needed!

- Building and Landscaping, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Using Pathways For Rain Catchment

Here in the drylands of San Diego we need to be especially sure to catch whatever rain may fall. Building good soil is vital for the entire planet because humans are going through decent topsoil like nobody’s business. Here at Finch Frolic Garden we’ve sheet mulched around trees to replicate decades of leaf drop, and on pathways to block weeds, prevent compaction and create good soil for shallow plant roots. We’ve also continued making our pathways work more for us by burying wood (hugelkultur) in the paths themselves. Most of our soil here is heavy clay, so creating drainage for roots is imperative. In sandy soils, creating more fungal activity to hold together the particles to retain water is important. We also need to store rain water when we get it, but not drown the roots of plants. This all can be accomplished by burying wood, the older the better.

Miranda and I have worked on many pathways, but for a few months this year the garden was given a huge boost forward with the help of Noel, a permaculture student and future farmer, who can move mountains in an afternoon with just a shovel.

The chosen pathways had these features: they were perpendicular to water flow, or were between trees that needed supplemental drainage, food and water access, and/or were where rainwater could be redirected. Eventually we’d like to do all the pathways like this but because of time, labor and materials we worked where it was most needed.

An area that becomes flooded when we have a deluge. The existing sheet mulch was pulled aside. Sections of the pathways were dug up (Noel’s work was very neat; my work is usually much less so). Wood was laid in the hole, and layered back with the dirt.

The pathway dug up and wood being layered. The nice, neat hole is Noel’s doing, not mine. Notice I said dirt, not soil. We don’t want to disturb good soil because we’d be killing microbes and destroying fungal networks. Dirt is another story; it needs amendment. As we’ve already buried all of our old wood, we timed these pathway ‘hugels’ to coincide with some appropriate tree removal.

You can be creative when cutting trees and make a chair! Watch out for sap on your pants, though. Trees were cut down and some climbing roses pruned back out of the pathway, and the green ‘waste’ was used in the nearby pathways.

This euphorbia was only sucking up water and not giving back anything, so it and its friends had to go. This one had a marking like an eye on it, and I was glad to see it go… as it was seeing me! Old palm fronds went in as well. No need to create additional work – good planning means stacking functions and saving labor.

The first layer of wood is covered with dirt, and then another layer added. After the wood was layered back with the dirt, the area was newly sheet mulched. Although the pathways are slightly higher, after another good rain (whenever that will happen) they’ll sink down and be level. They are certainly walkable and drivable as is. Although the wood is green, it isn’t in direct contact with plant roots so there won’t be a nitrogen exchange as it ages. When it does age it will become a sponge for rainwater and fantastic food for a huge section of the underground food chain, members of which create good soil which then feeds the surrounding plants. Tree roots will head towards these pantries under the paths for food. Rain overflow that normally puddles in these areas will penetrate the soil and soak in, even before the wood ages because of the air pockets around the organic material.

The best part about this, is that once it is done you don’t have to do it again in that place. Let the soil microbes take it from there. Every time you have extra wood or cuttings, dig a hole and bury it. You’ve just repurposed green waste, kept organics out of the landfill, activated your soil, fed your plants, gave an important purpose to the clearing of unwanted green material, and made your labor extremely valuable for years to come. Oh, and took a little exercise as well. Gardening and dancing are the two top exercises for keeping away dementia, so dig those hugels and then dance on them!

Burying wood and other organic materials (anything that breaks down into various components) is what nature does, only nature has a different time schedule than humans do. It takes sometimes hundreds of years for a fallen tree to decompose enough to create soil. That’s great because so many creatures need that decomposing wood. However for our purposes, and to help fix the unbelievable damage we’ve done to the earth by scraping away, poisoning and otherwise depleting the topsoil, burying wood hastens soil reparation for use in our timeline.

Another pathway is hard clay and isn’t on the top of my priority list to use for burying wood. However it does repel water due to compaction and because rainwater is so valuable I want to make this pathway work for me by catching rain. I’ve recommended to clients to turn their pathways into walkable (or even driveable) rain catchment areas by digging level-bottomed swales.

Digging gentle swales along a pathway can turn it into a rain catchment system. Make your paths work for you! A swale is a ditch with a level bottom to harvest water rather than channel water. However many pathways are on slopes or are uneven. So instead of trying to make the whole pathway a swale in an established garden, just look at the pathway and identify areas where the land has portions of level areas. Then dig slight swales in those pathways. Don’t dig deeply, you only have to gently shape the pathway into a concave shape with a level bottom. The swales don’t need to connect. You can cover the pathway and swales with bark mulch and they will still function for harvesting rain and still be walkable.

Mulching over the top makes the pathway even and still functional for rain catchment. If the pathways transect a very steep slope, you don’t want to harvest too much water on them so as not to undermine the integrity of your slope. This is a swale calculator if you have a large property on a steep slope.

So up-value your pathways by hugelkulturing them, and sheet-mulching on top. Whatever your soil, adding organics and mulching are the two best things to do to save water and build soil. And save the planet, so good going!

- Animals, Arts and Crafts, Birding, Building and Landscaping, Gardening adventures, Houses, Natives, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Water

A Mallard House

The Finch Frolic Garden Mallard Nesting Tube, by Miranda. For about four years now a pair of wild mallards have called Finch Frolic Garden home. They visit most of the year, especially in mating season as it is now. The male guards her closely as she goes off to lay an egg a day in some secluded, secret nest. This is Mrs. Mallard’s best time of the year.

Mrs. Mallard leading her mate all over the property as he protects her. She’ll stroll all over the property while he has to follow, and it is hilarious to watch. They get in more walking time now than in the whole year put together. She deserves to enjoy the attention because the rest of mating season isn’t so much fun for her.

The mating occurs in the water, with the male biting her neck and holding her head under water. Ducks have drowned during mating. A couple of years ago Mr. Mallard was losing his mating plumage and decided to allow a rather mean drake have at Mrs. Mallard. It was a violent mating, and she tried hard to get away.

Mr. Mallard and his terrible surrogate. The next time the imposter flew in Miranda and I were close to the pond by a lime tree, with some bushes between us and the pond. Suddenly we noticed Mrs. Mallard slowly walking around the bushes, her head held low. If she could have tip-toed with webbed feet she would have. She slowly approached us and hid behind the lime tree next to us. We took action and chased the males away, then spoke soothingly to Mrs. Mallard in a sense of female solidarity. It was quite touching to have a wild creature so trust us as to come to us for rescue.

The Mallards checking out the duck island. Once the eggs have been laid the female is entirely in charge of the eggs and the hatchlings. However, if the clutch fails, the male will keep re-mating with her and she’ll keep re-nesting. Mrs. Mallard has attempted to lay eggs on our property in the bushes, but rats or other creatures have eaten them. She had a nest right next to our garage one year, perhaps hoping that we could protect the eggs even though by the time we realize why we’d meet a duck on the pathway by the house every day it was too late. The stress of the mating, the egg production and laying is taxing to a wild duck’s health. Last year she appeared leading several ducklings to our pond. We have no idea how far she’d lead them, or how many there were to begin with, and we knew the babies probably wouldn’t last long. We were right; they were gone by the next day. Predation by the invasive bullfrogs in the pond, rats, weasels, hawks or any number of animals. So sad for the mallard family.

This year Mrs. Mallard has been disappearing daily, obviously to lay an egg a day elsewhere again. However Miranda decided to help out for future nests. She built a mallard nesting tube. Following instructions she found online from people who have proven this design works, she rolled the first three feet of a piece of 7’x3′ hardware cloth to form a tube.

A 7′ x 3′ piece of hardware cloth. Larger wire would let too much debris fall into the pond. This was wired together, and the last four feet was layered with natural plant materials and rolled.

The first 3′ are rolled and fastened, then Miranda lay dry cattails on the rest.

The nesting tube. Kind of like a jelly roll for mallards.

The inside of the tube isn’t large, but apparently it is large enough. This tube was wired onto a cradle she made mostly of recycled PVC parts, and painted dark green.

Gluing together the cradle. All of the pipe we had salvaged from old irrigation systems.

The cradle supports the tube, but is also loosely wired onto it.

A sprinkler riser is what will fit into the support pipe.  Also, to prevent hawks, egrets and other opportunistic birds from perching on top and snacking on eggs or hatchlings, Miranda attached strips of pokey chicken wire along the top.

Also, to prevent hawks, egrets and other opportunistic birds from perching on top and snacking on eggs or hatchlings, Miranda attached strips of pokey chicken wire along the top.

Since egrets visit the pond regularly, the top of the tube had to be inhospitable.

Miranda cut strips of chicken wire and these were bent and wired on top to prevent birds from landing. Slipping into the chilly February pond was a shock until our legs became acclimated (or “numb”). We pounded a hollow pipe, then slipped another pipe into it (both found materials), and then mounted the tube on top.

After mounting the nesting tube, Miranda stuffed leaves and dry grass inside, because mallards don’t carry in their own nesting materials. Miranda then lined the inside of the tube with soft nesting materials – dried grass and leaves – because mallards don’t bring them in. A little interior decorating for future lodgers. A sprinkler riser screwed into the PVC cradle slipped into the pipe. This way the nesting tube can be easily removed for maintenance. The tube is about three feet above the water surface.

Mrs. Mallard hasn’t shown any interest at this point, but she’s involved with her other nest right now. We have high hopes for a successful nest. Anyone want to come catch bullfrogs?

- Animals, Bees, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.Plant the appropriate plants for where you are placing them, for your soil and water use, and stack them in a guild with compatible plants that you can use. The ground will be covered by a foliar density that will keep grasses and other weeds at bay and provide excellent habitat for a full range of animals and insects. By stacking plants in a guild you are bringing life and abundance back to your garden.

Does it still sound so complicated? Rather than try to learn the roles of all the plants in the world, start small. Make a list of all the plants you want to plant. List them under food bearing, culinary/medicinal herb, craft/building material, and ornamental. Then read up on those plants. What size are they at maturity? Do they need full sun, partial or full shade? If trees, do they have an upright growth so you may plant under them (stonefruit), or do they like to have their roots covered and don’t like plants directly under them (citrus and avocado)?

Citrus doesn’t like plants under its canopy, but does like plants outside its dripline. Are they annuals, perennials or biennials? What is their growth habit: sprawling, rooting where they spread, upright bushy, do they need support and can they cling or do they need to be tied to a support?

Will the plant twine on its own? Do they require digging up to harvest? Do they fix nitrogen in the soil? Do they drop leaves or are they evergreen? Are they fragrant? When are their bloom times? Fruiting times? Are they cold tolerant or do they need chill hours? How much water do they need? What are their companion plants (there are many guides for this online, or in books on companion planting.)

Do vines or canes need to be tied to supports? As you are acquainting yourself with your plants, you can add to their categorization, and shift them into the parts of a plant guild. Yes, many plants will be under more than one category… great! Fit them into the template under only one category, because diversity in the guild is very important.

Draw your guilds with their plants identified out on paper before you begin to purchase plants. Decide where the best location for each is on your property. Tropical plants that are thirsty and don’t have cold tolerance should go in well-draining areas towards the top or middle of your property where they can be easily watered. Plants that need or can tolerate a chill should go where the cold will settle.

Once it is on paper, then start planting. You don’t have to plant all the guilds at once… do it as you have time and money for it. Trees should come first. Bury wood to nutrify the soil in your beds, and don’t forget to sheet mulch.

Remember that in permaculture, a garden is 99% design and 1% labor. If you think buying the plants first and getting them in the ground without planning is going to save you time and money, think again. You are gambling, and will be disappointed.

Have fun with your plant guilds, and see how miraculous these combinations of plants work. When you go hiking, look at how undisturbed native plants grow and try to identify their components in nature’s plant guild. Guilds are really the only way to grow without chemicals, inexpensively and in a way that builds soil and habitat.

You can find the rest of the 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries .

- Animals, Bees, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds

Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries

California native sage and penstemon make great insectiaries. Insectiaries are plants which attract lost of pollinators to the rest of your plant guild. We’re not just talking honey bees. Actually, what Americans raise and call honey bees, any bees from the genus Apis which are colonial honey-producers, are all European. Of course there are also the African honey bees which are loose in America, but their ‘hotness’ – their radical and violent protective measures – are not welcome. There are no native honey bees in North America.

What we do have are hundreds of species of bees, wasps and flies which are native and which do most of the pollenization in non-poisoned gardens and fields. Here in Southern California where everything is smaller due to the low rainfall we have wasps, flies and bees which range in size from the inch-long carpenter bees to those the size of a freckle. A small freckle. In fact the best native pollinator we have is a type of hover fly that is about the size of a grain of rice.

Hoverflies (Family Syrphidae) are one of our best pollinators. My daughter Miranda hosts our Finch Frolic Garden Facebook page where she has posted albums of animals and insects found here, with identifications along with the photos so that you can tell what is the creature’s role in the garden (you don’t need to be a member of Facebook to view it).

“This photo is of a minute parasitoid wasp (likely Lysiphlebus testaceipes) which preys on aphids. The aphids here are Oleander Aphids (Aphis nerii), which infest our milkweed bushes.” Miranda Kennedy We notice and measure the loss of the honeybee, but no one pays attention to the hundreds of other ‘good guys’ that are native and do far more work than our imports. Many of our native plants have clusters of small flowers and that is to provide appropriate feeding sites for these tiny pollinators. Tiny bees need a small landing pad, a small drop of nectar that they can’t drown in, and a whole cluster of flowers close together because they can’t fly for miles between food sources.

Oregano doesn’t spread as much as other mints do, and can be kept in check by harvesting. Look closely at the blooms in summer and you’ll see lots of very tiny insects pollinating! If you’ve read my other Plant Guild posts, you’ve already familiar with this, but here it goes again. You’ve heard of the ‘Three Sisters’ method of planting by the Native Americans: corn, beans and squash. In Rocky Mountain settlements of Anasazi, a fourth sister is part of that very productive guild, the Rocky Mountain bee plant (Cleome serrulata). Its purpose was as an insectiary.

Borage is edible, medicinal, lovely and reseeds. So planting native plants that attract the insects native to your area is just as important as planting to attract and feed honey bees. Many herbs, especially within the mint and sage families, produce flowers that are enjoyed by most sizes of insects and are useful as food or medicine as well.

You’ll remember our old friend comfrey, which is also a mining plant and great green fertilizer! It also is a dining room for bumblebees. If you like flowers, here’s where you can possibly plant some of your favorites in your guild and not feel guilty about it! Of course, aesthetics is important and if you aren’t enjoying what is in your garden, you aren’t doing it right, so plant what makes you happy. As long as its legal.

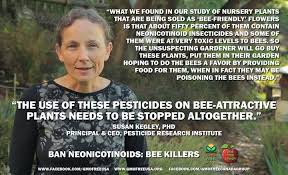

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.  Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.

Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.  Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

Talk about a sales twist! They don’t mention that it kills EVERYTHING else! When public demand is high enough, they will change their buying habits, and that will force change all the way down the line to the farmers. No matter how friendly and beautiful a nursery is and how great their plants look, insist that they prove they have insecticide-free plants from organic growers (even if they don’t spray plants themselves). Systemic insecticides are bee killers. And wasp and fly killers as well.

Of course many of the other guild members will also attract pollinators, and even be host plants for them as well. With a variety of insectiaries, you’ll receive the benefit of attracting many species of pollinator, having a bloom time that is spread throughout the year, and if a plant is chewed up by the insect it hosts (milkweed by Monarch caterpillars, for instance) there will be other blooms from which to choose.

Placing fragrant plants next to your pathways also gives you aromatherapy as you pass by.

And flowers are pretty. So plant them!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Soil, Water Saving

Plant Guild #7: Vines

Our varieties of squash several years ago. You may think that vines and groundcover plants are pretty interchangeable, and they can share a similar role. However, as we covered in the Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers these plants do not have to vine, but just cover large spaces close to the ground and coming from a single trunk or stem.

Sweet potatoes and yams make fantastic ground covers. The leaves are edible. Some root in one place, and some spread tubers over a larger area, so choose what is appropriate for digging up your harvest in your guild. They will die of frost. Vines can be large and heavy, small and delicate, perennial or annual. In a food plant guild vines are often food-bearing, such as squash. If you recall the legendary Three Sisters of planting – corn, beans and squash – there are two vines at work here. The corn forms a trellis for the light and grabby bean plant to climb upon (the bean fixing nitrogen in the soil as well as attracting pollinators with its flowers). The squash forms a low canopy all around the planted area. The big leaves keep moisture in, soften the raindrops to prevent erosion and deoxygenation, drop leaves to fertilize the soil, provide a large food crop, and attract larger pollinators. Even more than that, the squash protects the corn from raccoons. These masked thieves can destroy an entire backyard corn crop in a night, just when the corn is ripe. However, they don’t like walking where they can’t see the ground, so the dense squash groundcover helps keep them away.

Pipian from Tuxpan squash supported by a plum and a pepper tree. Vines are very important to use on vertical space, especially on trees. With global warming many areas now have extremely hot to scorching sun, and for longer periods. Intense sun will scorch bark on tender trees, especially young ones. By growing annual vines up the trees you are helping shade the trunk while producing a crop, and if the vines are legumes you are also adding nitrogen fertilizer.

Can you spot the squash in the lime tree? It is crescent shaped and pale. Be sure the weight of the mature vine isn’t more than the tree support can hold, or that the vine is so strong that it will wind its way around new growth and choke it. Peas, beans and sweetpeas are wonderful for small and weaker trees. When the vines die they can be added to the mulch around the base of the tree, and the tree will receive winter sunlight. When we plant trees, we pop a bunch of vining pea (cool weather) or bean (warm weather) seeds right around the trunk. Larger, thicker trees can support tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, and squash of various sizes, as well as gourds. Think about how to pick what is up there! We allowed a alcayota squash to grow up a sycamore to see what would happen, and there was a fifteen pound squash hanging twelve feet above the pathway until it came down in a heavy wind!

These zuchinno rampicante, an heirloom squash that can be eaten green or as a winter squash, form interesting shapes as they grow. These ‘swans’ and Marina are having a stare-off. Nature uses vertical spaces for vines in mutually beneficial circumstances all the time, except for notable strangler vines. For instance in Southern California we have a wild grape known as Roger’s Red which grows in the understory of California Live Oaks. A few years ago there appeared in our local paper articles declaiming the vines, saying that everyone should cut them down because they were growing up and over the canopy of the oaks and killing them. The real problem was that the oaks were ill due to water issues, or beetle, or compaction, and had been losing leaves. The grape headed for the sun, of course, and spread around the top of the trees. The overgrowth of the grape wasn’t the cause of the problem, but a symptom of a greater illness with the oaks.

Zucchini! Some vines are not only perennial, but very long-lived and should be placed where they’ll be happiest and do the most good. Kiwi vines broaden their trunks over time and with support under their fruiting stems can be wonderful living shade structures. A restaurant in Corvallis, Oregon has one such beauty on their back patio. There is something wonderful about sitting in the protection of a living thing.

Wisteria chinensis is a nitrogen-fixer with edible flowers (and poisonous other parts), has stunning spring flowers and can make a nice deciduous vine to cover a canopy. It does spread vigorously, but can be trained into a standard, and are fairly drought tolerant when mature. Passionvines can grow up large trees where they can receive a lot of light. Their fruit will drop to the ground when ripe. The vines aren’t deciduous, so the tree would be one where the vine coverage won’t hurt the trunk.

Dragonfruit aren’t exactly a vine, but they can be trained up a sturdy tree. Vines such as hops will reroot and spread wherever they want, so consider this trait if you plant them. Because the hops need hand harvesting and the vines grow very long, it is probably best to put them on a structure such as a fence so you can easily harvest them.

So consider vines as another important tool in your toolbox of plants that help make a community of plants succeed.

Next in the Plant Guild series, the last component, Insectiaries. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants

Artichokes are mining plants, but also have a low enough profile to be a groundcover plant. They make excellent chop-and-drop. Flanking are lavender, scented geranium (left), and borage. In most ecosystems that offer easy food for humans, the ground needs to be covered. Layers of leaves, organic matter from animals (poo, fur, carcasses, meal remains, etc.) , dropped branches and twigs, fallen flowers and fruit, and whatever else gravity holds close to the earth, compost to create soil and retain water and protect the soil from erosion and compaction. Areas that don’t have this compost layer are called deserts. If you want to grow an assortment of food for humans, you have to start building soil. Even in desert communities where there are some food plants growing, such as edible cactus, mesquite beans, etc., there is biodiversity on a more microscopic scale than in old growth forests. In deserts the soil needs to absorb what little rain there is and do it quickly before it evaporates, and plants have leaves adapted to have small leaf surfaces so as not to dry out, and there are few leaves to drop. Whereas in areas where there are large forests the weather is usually wetter, tall plants and thick underbrush provide multiple layers of protection both on the plants and when they fall to layer the earth.

Nasturtium reseeds itself annually, is edible with a bite of hotness, detracts aphids from other plants, and is charming. Don’t let it get away in natural areas, though. A quick way to build soil in plant guilds is to design for plants that will cover the ground. This isn’t necessarily the same groundcover as you would use to cover embankments. For instance, iceplant can be used in a pinch, but it really isn’t the best choice in most plant guilds unless you are in a very dry climate, and your plant guild is mostly desert-type plants: date palm, etc. Annuals can be squash or other aggressive food-producing vines such as unstaked tomatoes. However you don’t need to consider just ground-hugging plants; think sprawling shrubs.

Scented geraniums are a great ‘placeholder plant’. These Pelargoniums (not true geraniums) come in a wide variety of fragrances. We’ve found bird nests in these! When guests tour through Finch Frolic Garden, they often desire the lush foresty-feel of it for their own properties, but have no idea how to make it happen. This is where what I call ‘placeholder plants’ come in. Sprawling, low-cost shrubs can quickly cover a lot of ground, protect the soil, attract insects, often be edible or medicinal, be habitat for many animals, often can be pruned heavily to harvest green mulch (chop-and-drop), often can be pruned for cuttings that can be rooted for new plants to use or to sell, and are usually very attractive. When its time to plant something more useful in that area, the groundcover plant can be harvested, used for mulch, buried, or divided up. During the years that plant has been growing it has been building soil beneath it, protecting the ground from compaction from the rain. There is leave mulch, droppings from lizards, frogs, birds, rabbits, rodents and other creatures fertilizing the soil. The roots of the plant have been breaking through the dirt, releasing nutrients and developing microbial populations. Some plants sprawl 15′ or more; some are very low-water-use. All of this from one inexpensive plant.

Squash forms an annual groundcover around the base of this euphorbia. Depending upon your watering, there are many plants that fit the bill, and most of them are usable herbs. Scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.), lavender, oregano, marjoram, culinary sage, prostrate rosemary, are several choices of many plants that will sprawl out from one central taproot. Here in Southern California, natives such as Cleveland sage, quail bush (which harvests salt from the soil), and ceanothus (California lilac, a nitrogen-fixer as well), are a few choices. Usually the less water use the plant needs, the slower the growth and the less often you can chop-and-drop it. With a little water, scented geraniums can cover 10 – 15 feet and you can use them for green mulch often, for rooted cuttings, for attracting insects, for medicine and flavoring, for cut greenery, for distillates if you make oils, etc.

Sweet potatoes make a great ground cover. Choose varieties that produce tubers directly under the plant rather than all along the stems so that you don’t have to dig up your whole guild to harvest. Groundcover plants shouldn’t be invasive. If you are planting in a small guild, planting something spreading like mint is going to be troublesome. If you are planting in larger guilds, then having something spreading in some areas, such as mint, is fine. However mint and other invasives don’t sprawl, but produce greenery above rootstock, so they are actually occupying more space than those plants that have a central taproot and can protect soil under their stems and branches. Here at Finch Frolic Garden, we have mint growing freely by the ponds, and in several pathways. Its job is to crowd out weeds, build soil, and provide aromatherapy. I’d much rather step on mint than on Bermuda grass, and besides being a superb tea herb, the tiny flowers feed the very small bees, wasps and flies that go unsung in gardens in favor of our non-native honeybees (there are no native honeybees in North America).

Here’s a general planting tip: position plants with fragrant leaves and flowers near your pathways for brush-by fragrance. You should have a dose of aromatherapy simply by walking your garden path. Mints are energizing, lavenders calming, so maybe plan your herbs with the pathways you take in the morning and evening to correspond to what boost you need at that time.

Consider groundcover plants and shrubs that will give you good soil and often so much more.

Next up: Vining Plants.

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

What makes up a plant guild.