-

The Fine Art of Pleaching or Plashing

Pleaching in the sky. My daughter and I pleached today, although I’ve had the pleasure of pleaching before this , and even later. Pleaching, or its synonym plashing, refers to the interweaving of branches, both live or dead. Basketry is one form, but more notably is the pleaching of living branches to form secure living fences, buildings or artwork. The withy (willow) bird hide (a covered place from which to watch birds) is a living building I planted two years ago. We pleached our withy hide today. Not many people can say that! (or admit to it).

Pleaching is where stems, usually from two plants, grow together. Pleaching can be done on many vigorous trees such as willow, or even fruit trees such as plum. The branches grow together making separate plants become part of a whole. The trees then share nutrients and water and can pull what it needs from roots a long distance away.

Curly willow is beautiful on its own. Pleaching essentially makes many plants into one living organism. Pleached hedgerows make a living barrier to keep in livestock; pleached trees can be woven into furniture, living artwork, decorative fences, and living trellises. Pleaching livestock fences was practiced a lot in Europe prior to the invention of barbed wire, and then was forgotten for awhile only to be revived as a form of artistic gardening.

This trunk unfortunately cracked while I pulled on it. As it is willow, it will heal quickly. My daughter used the opportunity to put a twig from the next willow through the crack, which will grow over it. Today I of course, as is my habit, waited until the sun was directly above the area where I was working so that I had to look into it as I worked. I don’t recommend this, however. My daughter used a fruit-picking pole to snag some of the taller, whippier branches of the curly willow that make up the withy hide. I stood on a ladder, squinting, and pulled two branches together.

Me on a ladder reaching over my head to pull two branches together to form a roof. To insure that you have a good pleach going, it is best to lightly scrape the bark from both pieces just where they are going to meet; something like you see blood brothers do with their hands in the movies, but with no blood involved.

Lightly scraping the bark from both branches where they will meet is important. Next time I’ll use a vegetable peeler, which will allow me better angles. Then you make sure the pieces fit snugly, then tie them on. I’ve use various materials to do this. Twist-ties hold securely but the wire can eventually girdle the growing branches. Twine is more difficult to use in that it doesn’t grip the branches well enough for a firm hold, but it will eventually break down, hopefully after the pleach is successful. This time I used green tree tape. It grips well, is easy to tie, and will stretch with the growing branches and eventually break. The green color won’t be noticeable when the willow leafs out, either.

Tying the scraped branches together so they stay put. They can’t move around in the wind or they won’t be able to grow together. As I pleached from the top of the ladder, working overhead while the sun and curly twigs attacked my eyes, my daughter pleached pleasing arches over the ‘windows’ of the hide.

Weaving curly willow can be a twisty challenge. The hide looks lopsided because the willows on one side have found sent out roots to drink from the small pond. With more pleaching, the thirsty trees on the other side will probably take advantage of that water source, too, and have a drink via their overhead connection. I think it is part of its charm. A half-wild building.

The withy hide as a duck on the big pond sees it. The willow is just about to begin leafing out. Try pleaching a small fence or a living bench or chair. It is tremendous fun and if you don’t like it, you can always cut it down. Oh, and work on a cloudy day.

A willow roof. - Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Soil

More Spores: Planting Garden Giant and Shaggy Mane Mushrooms

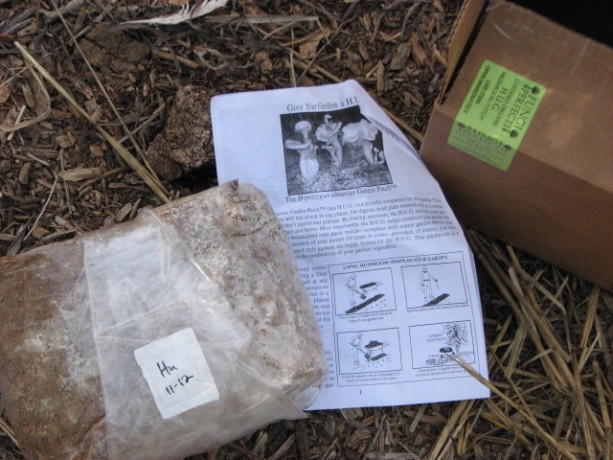

Breaking apart the large square of inoculated sawdust. The last scintillating post was about how we distributed oyster mushroom spawn in the straw in our new vegetable garden. Today we planted more shrooms… but not the last! “Where will it end?” you cry. I’m not sure myself; I guess it depends on how well we can grow mushrooms here in the drought-stricken west. It is the last week in February and we’ve had 70 degree – 90 degree daytime temperatures all month long, and less than a 1/2 inch of rain this year. This is our rainy season. Some mushrooms do grow here, although they aren’t very apparent this dry year. We certainly don’t have the high humidity, frequent rain and acidic loam that characterizes areas such as Northern California and the Pacific northwest where mushrooms are everywhere.

Shaggy Mane spores growing all over the bag. I bought two bags of spores, of Giant Mushroom and Shaggy Mane mushrooms, both of which are edible and can stand warmer climates, as long as they are shaded and receive water. My daughter and I strolled all over the property considering different spots. There aren’t a lot of areas which are shaded all day, which receive water or are close to water, and where shrooms would be safe from nibbling animals. We decided upon the small group of old lime trees (and one orange) that are between the fenced backyard and the Fowl Fortress.

Limes look so very pretty, until they draw blood! I’m not a fan of lime trees. When I was 11, my parents moved me and my sister to a four-acre lime grove in Vista, CA. I grew up enjoying the smell of lime blossoms, walking through tens of thousands of bees (pre-Africanization), climbing up the few avocado trees and pretending I was a spy and bad guys were looking for me. But when I was older I was paid to care for the lime trees. I became disenchanted. They are nasty. Their thorns and small dead twigs scratch and catch, they are often full of ants which are harvesting aphids on the leaves, and they are short trees, so to pick limes or do anything for them you have to duck under the canopy and usually end up losing some hair and bleeding from the thorns.

A group of citrus trees, with logs cut for mushroom inoculation and some old chicken wire that is ready for a hugelkultur burial. So of course as an adult I moved onto property with a lot of lime trees on it. Limes aren’t very profitable, either. I keep the trees because I don’t water them yet they thrive, and I don’t believe in killing trees for no reason. Now their canopy can be put to good use.

We always find some lost treasure from the previous property owner. I purchased organic mycelium from Paul Stamet’s Fungi Perfecti. He wrote many books on growing mushrooms and has had startling results using oyster mushrooms for soil remediation and with turkey tail and other mushrooms for fighting cancer and other illnesses. Mycelium Running is an incredible book.

Clearing a level area under a lime tree. For the Garden Giant shrooms, we hacked through dead branches and pulled away a lot of red apple iceplant that has slowly been taking over from the neighbor’s property. We dug about two inches into the ground to help insulate the wood chips that would be placed in there, and watered it in well with what was left of the rain water from our large tank.

Mycelium is already busy around the roots of the lime and ash trees, even in this dry ground. We’d just received a truckload of chipped oak from landscapers, and that was perfect for this variety of mushroom. We spread out a couple of inches of chips, watered it well, spread the inoculated wood chips on top,

Spreading the mycelium… so many little spores! spread a couple more inches of chips over, mixed them up with our hands to spread the spores throughout the chips, and watered again. With luck, they should be up in a couple of weeks.

The final Garden Giant bed. Next to another tree we dug a 3×3 area just an inch down. Shaggy Mane lives in vegetative compost rather than the highly fungal wood chips, and can live in a variety of stuff.

Vegetative compost mixed with straw and leaves for this long-term mushroom. We removed the more composted stuff from our cold compost bin and mixed it with very poopy straw from the chicken coop (thanks, girls!), and ash leaves. The spores were mixed well into this combination and watered in.

Mixing in Shaggy Mane spores with the compost. I topped it with leaves just to help keep the moisture in. We won’t see production from these until next winter when the temperature drops to below 60 degrees F. When they do ‘fruit’, as the mushrooms are called, we can add new compost alongside and the spores will creep over for another year’s growth.

To assist with the moisture I’m going to have the greywater empty along these trees to keep the ground moist and the humidity up. Also, there are drip lines from the well along here and I think the addition of some above-ground sprayers will handle our watering needs without using domestic water.

The white tables are set under an orange tree, and are where inoculated logs will go. Under the orange tree, which is a fine tree but very neglected and hidden by the vicious lime trees, we decided to set up for our next installment of mushroom growing. We’ll be drilling holes in oak logs and growing four kinds of shrooms on them. I’m sure you just can’t wait!

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

Planting Spores in the Garden

The mycelium is white in the sawdust and ready to go. If you remember the trenching, filling and designing the new veggie patch, then this post will make more sense to you.

The next step was to cardboard the pathways where Bermuda grass has been taking over, then mulch them as well. The mulch makes it all look so nice!

Covered with mulch, the cardboard is only a memory. Next it was time to plant. We’d already transplanted three-year old asparagus, and hopefully not shocked them so much that they won’t produce well this year. The flavor of fresh asparagus defies description.

Asparagus popping up some feather shoots from its new home. The strawberry bed was older and completely taken over by Bermuda grass, so it all was buried and I purchased new organic and extremely reasonably priced bareroot strawberries.

A bundle of twenty-five strawberries. I purchased two June-bearing types and three ever-bearing, heat-loving types, from www.groworganic.com. When they bloom this year we’ll have to nip off the buds so that next year when their roots have taken hold and fed the crown, we can have lots of strawberries.

Soaking the strawberry roots for a few minutes rehydrates them. We planted some in the asparagus bed, which will do nicely as groundcover and moisture retention around the asparagus, while the asparagus keeps the heat off the strawberries. Some we planted around the rock in the center of the garden. The rest will be planted around fruit trees as part of their guilds.

Strawberries surround the rock. We also planted rhubarb in the asparagus bed; these poor plants had been raised in the greenhouse for several months awaiting transplanting.

Rhubarb, really eager to be put in the ground. Hopefully the asparagus will protect them from the heat. I plan to raise more rhubarb from seed and plant them in other locations on the property, aiming for the coolest spots as they don’t like heat at all.

With a strong knife (weak blades may snap) cut a cross in wet cardboard the pull aside the edges. The way to plant through cardboard is to make sure that it is wet, and using a strong knife make an x through the cardboard. Use your fingers to pull the sides apart. Stick your trowel down and pull up a good shovel full of dirt (depending on how deeply your plant needs to go.

Insert a trowel through the hole and scoop out some dirt. The base of plants and the crowns of strawberries should all be at soil level. Seeds usually go down three times their size; very small seeds may need light to germinate). Gently plant your plant with a handful of good compost, then water it in. You won’t have to water very often because of the mulch, so check the soil first before watering so that you don’t overwater.

Don’t forget to water in the plants! For the first time in years I ordered from the same source Jerusalem artichokes, or Sunchokes as they’ve been marketed. They are like sunflowers with roots that taste faintly like artichoke. We planted some of them in one of the quadrants, and the rest will be planted out in the gardens, where the digging of roots won’t disturb surrounding plants.

The oyster mushroom kit, or H.U.G. You’ll have to visit Fungi Perfecti to read up on it. Most excitingly, we’ve purchased mushroom spores from Fungi Perfecti, which is Paul Stamet’s business, the man who wrote Mycelium Running and several other books about growing mushrooms for food and for health. We bought inoculated plugs, but that will be another post. Almost as exciting are the three bags of inoculated sawdust to spread in the garden! They sell an oyster mushroom that helps digest straw and mulch, while boosting the growth of vegetables and improving the soil. You also may be able to harvest mushrooms from it! Talk about a wonderful soil solution, rather than dumping chemical fertilizers on the ground!

We’d already covered our veggie beds with wet cardboard and straw.

Really good soil from what is now a mulched pathway. To give the mycelium a good foundation I dug up good soil from one of the field beds, which needed an access path through the middle. By digging out the path I created new water-holding swales, especially when filled with mulch.

We pulled aside the straw. In the veggie garden we raked back the straw and lightly topped the wet cardboard with soil. On top of that we sprinkled the inoculated sawdust.

Good soil over cardboard. On top of that we pulled back the straw and watered it in.

Sprinkling spore-filled sawdust over the soil. The fungus will activate on the wet soil, eat through the cardboard to the layers of mushroom compost and pidgin poo underneath that and help make the heavy clay beneath richer faster.

The fungi will immediately begin to colonize the wet soil. We treated the two top most beds which have the worst soil, the sunchoke bed and the asparagus bed. In four to six weeks we may see some flowering of the mushrooms, although the fungus will be working even as I sit here. There are several reasons why I did this. One, it is just totally cool. Secondly, there is no way for me to purchase organic straw. By growing oyster mushrooms in it, I’m hoping the natural remediation qualities of the oyster fungus will help cleanse the straw as it decomposes. Oyster mushrooms don’t retain the toxins that they remove from soil and compost, so the mushrooms will still be edible. Fungus will assist rebuilding the soil and give the vegetables a big growing boost. I know I’ve preached that vegetables like a more bacterial soil rather than fungal. This is true, except that there are different types of fungus. If you put wood chips in a vegetable bed, you’ll activate other decomposing fungus that will retard the growth of your tender veggies; the same wood chips around trees and woody plants will help them grow. However these oyster mushrooms will benefit your veggies by quickly decomposing compost and making the nutrients readily available to the vegetables. Their hyphae will help the veggie’s roots in their search for water and nutrients, too.

Straw is over the top and watered. We can continue to plant in the beds as the fungus does its magic. The other two bags of inoculated spores are for shaggy mane and garden giant, which we’ll find homes for in compost under trees. More on that as we progress. It is so nice to be planting, especially since these are perennial plants where the most work is being done now. Now we just need some rain!

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Water Saving

The Sunken Bed Project… Finis!

Maybe they can see this from space? To take up where we left off in this exciting saga, we had the hugelkultur trenches buried, the pattern outlined in gypsum, and a boulder moved. On top of the beds I spread the cleanings of a pigeon coop, courtesy of our good friends and neighbors who raise and rescue many pigeons.

Pigeon poo and coop gleanings all over the garden beds. Yum! The high nitrogen poo, feathers, and leftover pigeon peas and other food items will make a wonderful breakfast for microbes. On top of that I spread a pickup truck bed full of mushroom compost. Jacob was nice enough to clean out his truck and help me get a load. The nearby mushroom farm raises shiitake and button mushrooms on logs of compressed sawdust. This is a high fungal compost, and slightly acidic. Since we have a high alkaline soil, this is okay.

The garden beds covered with mushroom compost. After the compost begins to make its final decomposition, the worms thrive in it. I managed to wheelbarrow down the entire load and spread it just before we had the first rain event of the year…less than 1/4″, but enough to give the garden a small soaking.

Cardboard is on all the garden beds. How nice to clean up all that cardboard and newspaper that we’ve been collecting! Today my daughter and I started in on the final treatment. We covered all the beds with cardboard, and all the pathways with newspaper. This thin layer will hold in moisture, and help retard the growth of the dreaded Bermuda grass.

Spreading damp newspaper on the pathways. I’m really hoping so, anyway. Another small storm was blowing in for tonight, scattering our newspapers although we wet them down thoroughly. We’re still using water from the 700-gallon tank that catches water from the house’s raingutters. We’re trying to use some up so that fresh water can enter the tank with this storm.

Watering down the newspaper with rainwater from the tank to keep the wind from undoing all our work, and starting the decomposition process. Although we were both very tired and getting cold, we needed to cover the paper. I hauled down about fifteen wheelbarrows full of mulch; this had been dumped in the driveway courtesy a landscaper with a chipper. Miranda spread the mulch over all the pathways, which looked just great.

Paths covered in mulch. We almost stopped there, but I was driven to finish this project today. We pitchforked used straw from out of the Fowl Fortress, broke open some other bales, and mulched the garden beds heavily with the straw. And…. we’re done! Yipee! The rain tonight will give it all a good soak, and soon we can begin planting in our snazzy new garden beds.

The beds covered in straw! Hurray! I admit that I thought the beds would look more sunken, but with three 2′ deep x 30′ long trenches underneath there is a lot of underground moisture for the topsoil to absorb. Also the beds are below the pathways, but with the height of the cardboard and straw they don’t look it. With the garden on a slope we had to make some adjustments.

The next exciting project that we’ve already begun working on is growing mushrooms! Stay tuned.

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Vegetables

The Sunken Bed Project, Part 3

The un-raised bed as of this morning. Today my daughter and I made good headway in the completion of the garden. In the morning the bed still had some veggies that needed transplanting, the ground needed smoothing, the giant clumps of asparagus plants we’d hauled out needed to be planted right away because they were already trying to come out of dormancy, and we certainly didn’t want to lose this spring’s crop.

Transplanting and some fine-tuning by the girls. We let the girls loose since we were watching out for coyotes. They loved the grubs and unfortunately, the valuable worms too. Lark, the barred rock in the foreground, was up to her old tricks of jumping onto my shovel and quickly kicking half the dirt off in search of bugs. Miranda painstakingly dug up lots of salad greens for transplanting. We both dug up and pulled out lots of Bermuda grass as we went. The trash cans are full of it.

The difference between the heavy clay and the good garden soil is striking. While digging those 2 foot deep trenches we unearthed a lot of clay. On the surface the colors of what had been good garden soil next to what lay under it was very clear. With the deep hugelkultur beds and the sheetmulching, all this clay will be turned into microbial rich soil.

We measured off and marked the pathways and beds with gypsum. Finally we were able to measure off and draw out the design of the garden. We used gypsum which is good for the soil. So many people use spray paint to mark the ground… just don’t! Toxic fumes and toxic chemicals in the soil. If you don’t have gypsum, use flour! The light is bright in the above photo so you can’t see the design so well. We had carefully drawn out several designs on graph paper. An intricate Celtic design was the most favorable one until I’d realized the garden wasn’t square but rectangular. It was just as well because it would have been a nightmare of measuring. This one has 2′ wide pathways from prime entry angles (a wheelbarrow can fit), each planter bed is easily reached from all sides, and the circular design is pleasing and fun.

There was this rock…. There was a big flaw in the plan. There was this boulder that had been placed during the original construction of the garden. It didn’t serve a purpose, it was always in the way, it was a shelter for Bermuda grass, and it wasn’t attractive. Now it was at the head of one of the pathways. It had to go. My daughter and I decided to move it to the center of the garden. After transplanting the heavy batches of asparagus, we dug out a hole for the rock to sit in; when placing boulders it is visually more attractive if the boulder is buried at least a quarter of its size into the ground to look natural. We placed wet newspapers around the hole so that the boulder would sit on them and they would block Bermuda grass from emerging.

One of the methods used to move the rock, and build up good bone density and muscle. Although the garden was sloped down from the boulder, the rock wasn’t round and didn’t want to roll. We dug out a pathway for it, and using a long crowbar and a digging bar we managed to turn it over. We pushed and heaved and balanced and flipped it until it was right at the rim of the hole, and then things became difficult because it wasn’t positioned in the way we wanted it. The rock has a flat side, and is long. Miranda suggested that the tall side should stand up for birds to perch on, and I liked the Half-Dome look to it. We heaved the rock into the hole, then walked it around, tipped it up, centered it, and eased it into place, using the bars and all of our strength. Luckily the boulder didn’t roll on a foot, or the bar slip and break my collarbone. Finally we tiredly decided that the position it was in was good enough and we were both happy. Exhaustion had much to do with this decision. Miranda propped it up with clay chunks as I held it in place with the digging bar, then backfilled around it. It looks fantastic; a good central point for the garden, and a source of thermal retention.

The rock in place, gathering positive cosmic forces and good karma. At least, I hope so. We messed up some of our pathway lines, but we can easily redraw them. The sun was setting and the mosquitoes humming; the Pacific chorus frogs began calling by the hundreds, and the wigeon came in to feed on the pond. There were still chores and dinner to be had, but exhausted as we were, we were pretty darn proud of ourselves for moving that big guy by ourselves. Next comes the sheet mulch.

A Maxfield Parrish sunset. - Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Rain Catching, Soil, Worms

The Sunken Bed Project, Part Two

Old wire can be buried! Remember the trenches? We lined the trenches with old rusty wire, to rot, add iron to the soil, and discourage rodents. Mostly just to get rid of it. Inside the wire we lay old wood; in this case, the half-rotten sides of the old raised beds, nails and all. Fabric can be buried, too! Pet bedding no longer fit for man nor beast. Except for microbes of course. Around the wood we packed old fabric, most of which had been dog or cat bedding after long use in the house. There was also this futon! It had been a bed for years, and then it was the bed for the dogs for years. And for some mice. It took a little cutting and pulling to separate the cotton batting and the foam. Although the foam isn’t made from a natural material, it will eventually rot, but meanwhile will function like a ginourmous buried sponge for rainwater! The futon slices layed in the trench. Yipee! The stinky old futon is gone! Lots of branches, twigs, and woody materials were added, as was some year-old humanure, urea, and fallen limes. Nasty prickly lime tree branches, too. Serves them right for scratching me! After layering the trench materials with soil I used palm fronds for the top organic layer. Every step was watered in. Our 700-gallon water tank, formerly an organic fertilizer tank which Jacob managed to have donated, catches some of the roof rainwater. It has more than enough to water in this project, and then if it ever rains again the tank will be empty and ready for fresh water. The trenches filled in. Futons, scrap wood, woody bits, old stinky fabrics, manure… its all buried and ready to turn the clay into a microbial wonderland. We hauled chunks of extra clay up the hill and staged it by the upper pond, which needs to be resealed. Good leg exercise. The long hugelkultur strawberry bed was above ground, so it had to be reworked. We dug out the wood, wrestled out the wire, dug down about a food then lay the wire back down. There were gopher tunnels under the wire where they had come up and smashed their little noses against the wire. The wood that had been buried for a year was full of life! There were many very cool fungi. Tiny centipede-type decomposers eating away at the wood, all of which had been underground. More great fungus. On top of the wire went some more old textiles, then most of the old wood. Bunches of herbs that had been gathered for wreathes and not used were tucked in around the wood. Worms love thin woody stuff. Pigeon guano, thanks to our neighbor who delivers, was sprinkled over it all. Everything was well watered with rainwater, and then covered up. Next time: design, replanting asparagus, and perhaps even the final product! - Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving

The Pros and Cons of Raised Beds

The raised beds. Raised garden beds can be wonderful things. They also can be inappropriate. I’m in the process of taking ours down and replacing them with… well, I’ll describe it later on. Let’s get back to the pros and cons of raised beds.

Here are some of the pros:

Raised beds look just great. They are neat, tidy, organized and restful to the eye.

If raised high enough they are accessible to those who can’t work on the ground or bend over, and to those who are non-ambulatory.

If lined with hardware cloth they keep gophers and mice from tunneling under your food and making it magically disappear.

They help with some weed control.

If you live in a rainy area, they help with drainage.

If you have miserable soil, you can garden anywhere by building a raised bed without having to dig.

If you live in a cold area, depending upon what materials you use for the sides of the raised beds you can tap into the thermal heat and have warmer soil longer.

You can build reusable covers for the beds and turn them into cold frames, or shade structures.

Now here are some of the cons:

You need to fill raised beds with a lot of soil, and if you have to buy it, that is a large expense. The soil will compact and disappear over the course of a year, so you have to keep topping up the beds to keep the soil level high. Heavy work that is expensive.

Wire underneath the raised beds will last a few years and then will be compromised by rodents, so the bed will have to be emptied and rewired if rodents are a problem.

If you live in a warm, dry climate, the sides of the raised bed acts like a clay pot. It will wick moisture from the dirt and heat the dirt up so that plant roots around the perimeter will cook.

If you live in a warm climate you have to pour on the water because of the point mentioned above; a raised bed dries out much more quickly than in-ground gardens.

We are wealthy in clay. A Bermuda grass root hangs like a piglet’s tail from this clump. I built raised beds from old bookshelves many years ago, and that was my only veggie garden on the property as I raised my children. I’d grown plants in-ground before that, trenching and turning, and losing the fight against gophers and Bermuda grass. The raised beds were lined with wire. For awhile it worked, but the Bermuda grass took over and infiltrated all the beds. The wire began to rot and rodents chewed away at the sweet potatoes. Worst of all, the soil level would decrease, and since the beds weren’t very deep, then root veggies would grow into the wire and I’d lose half of them as they broke off during the harvest. I couldn’t keep up with refilling the beds. I composted in place, buried wood and vines, and that worked well, but I still needed to add compost. The beds drank up water during our long, hot summers.

The trenching begins. This summer I realized that I was using a gardening technique that was best suited to rainy climates. Here in the dry Southwest, a traditional gardening method was to plant in sunken beds. We need to capture water, not make it run off. Also, the Bermuda grass became so invasive that I realized that only sheet mulching would make any difference in controlling it.

Of course I decided that my daughter and I couldn’t possibly have an easy winter, but must rip out the beds and start digging.

In the trenches. I’m an advocate of no-dig gardening; however sometimes you have to dig bad soil to create good soil. The no-dig policy can happen once the infrastructure is in place. So here’s what I’m planning on doing: I’m combining hugelkultur with sunken gardens and sheet mulching to create what I hope will be a veggie garden with a much lower water consumption, and weed-free.

First we determined the direction of water flow down the hill, and planned on creating trenches that would capture that water. The trenches, or swales, would need to be level on the bottom so that any water flowing in from the downhill side, would travel all along the swale even to the drier side, where the surface soil was higher. We created a bunyip to estimate the difference in slope between the top and bottom of the garden. Although I had drawn up intricate plans for a square garden, that shape just wouldn’t work so we went with a rectangle. Then we began to dig. The first ten inches wasn’t bad, but after that we hit clay. I had to buy a mattock. I also ended up icing my back for a couple of days. Some of the clay we’ll save for use on any future earthworks we may want to do, and some we’re saving for an artist friend.

The soil was good for about ten inches, then we hit clay. The trenches are two feet deep, and about one to one and a half feet wide. It is amazing how you start out large, and then after a few very hot afternoons scraping clay and throwing it up and over four feet, the trenches become more narrow. My plan is to fill the bottom foot of the trenches with old wire, wood, branches, old textiles and other biodegradable debris. The old wire will rot, and will also help repel gophers. On top of all this will be layered some of the clay, and watered in with compost tea brewed in the 700-gallon water tank that is full of rainwater from the last rain (two months ago!). On top of that will be good soil, smoothed below the surrounding surface level. Water from the road will be diverted into the swales, which will allow it to flow across the garden and be absorbed by the fill materials. But what about the Bermuda grass? There isn’t a mountain of cardboard all over my garage for nothing! The entire garden will be sheet mulched, and all veggies will be planted through the cardboard and newspaper. The existing asparagus bed will need to be carefully relocated, but everything else can either be harvested or dug under.

These first two trenches will collect rainwater from the pathways and channel it the length of the garden. That’s the plan, anyhow. I’ll let you know how it goes.

- Arts and Crafts, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Soil

Bunyips: Fun to Say, Easy to Make and Use

Making a bunyip. Hi! I’m back. Its not as though I’ve been vacationing. Someday I might tell you about how important it is to question your doctor, about how under-producing thyroids affect every part of your body, about neighbor’s in-laws who skip their meds for a day and crash through your gate, and about strange and fatal chicken illnesses, but not today.

My big garden project for the winter is to turn the raised vegetable bed area into a sunken hugelkultur sheet-mulched vegetable area. I’ll go into details about that in another post as well. What I am going to describe is how to take measurements using a bunyip.

A bunyip is a water level that you can make very inexpensively and quickly, which relies upon gravity to give a reading. It even works around corners. I really don’t know how it came to be called a bunyip… its an Australian thing. A bunyip is an ancient aborigine water monster. More recently the name has come to be synonymous with imposter. Maybe this simple home-made water level is impersonating a laser level. Maybe bunyip is just so gosh-darn more fun to say.

Anyway, if you need to measure the difference in elevation, use a bunyip. If you want to find level ground, for instance if you are building a level swale on contour, use a bunyip.

The equipment for your bunyip are: two slim boards with at least one end flat, and at least 5 feet tall. You also need about 30 feet of clear fishtank hose. A waterproof marker, a ruler, a level and six pieces of wire to tie around the posts, and you are ready to go. If you have a couple of corks or stoppers that fit in the tops of the tubing, it will make it easier to carry without receiving a surprise shower.

You will need two slim posts, 30′ of tubing (the only kind I could buy in town was for cleaning fishtanks, hence the threaded ends. You don’t need these!), a ruler, wire and a waterproof marker. Be sure at least one of the ends of each board is flat, which will be what touches the earth when measuring. Along one of the boards begin to mark off inches (or centimeters) from the top. Make the marks readable from a short distance. Number the inches beginning with 1 at the top of the post, down to at least four feet (if you are measuring more dramatic slopes you’ll want to mark off more). Numbering from the top down allows you to do simple subtraction easily without becoming mixed-up, especially when you’re tired.

Using a ruler or yardstick (or meterstick), mark inches down from the top of the post. Next, stand the two posts together on level ground, making sure they are straight. It doesn’t matter if the tops aren’t exactly even, just the bottoms. Now with the two posts standing on even ground, mark the second post in one spot evenly with a mark on the first post; it doesn’t really matter which inch you mark because you can then use the ruler to fill in all the others.

With the bottoms of each post level, begin to mark the second post from the top, even if the tops of the posts aren’t even. So, using that mark and a ruler, mark inches all along the second post. The point is that the measurements are even from the bottom of the posts, where they will be resting on the ground.

You will have two posts with inches marked from the top. That done, tie the tubing onto the posts, allowing the tubing to reach a little higher than the top of the posts. The tubing in the photo is all I could find in town, and it is an extension for a fish tank cleaner, hence the threaded ends. You don’t need threaded ends, just the tubing.

Wire the tubing onto the posts, allowing the top of the tubing to be above the top of the post. With the tubing tied to the marked posts, you are almost ready to measure. Having someone to hold a post really helps here. With both posts straight up, fill the tubing with water. You can use a watering can (with the spray end off), or a hose. A funnel might help. Fill the tubing as completely as you can, but don’t worry about having the water go end to end. A gap at either end is okay.

Miranda holding the completed and filled bunyip. Work the air bubble out of the hose by lifting the bottom. Take out the air bubbles by lifting the center of the hose and feeding the air bubble through.

You are ready to measure!

The tubing doesn’t need to be off the ground to work; it can even work around corners. One person stands with their side of the bunyip at one area you want to measure, and the other person stands at the other. You don’t need to make the tubing lift off the ground; it will accurately measure with the tubing in almost any position. The water in the tubing will bob around; tap the top of the tubing with your finger to help it settle faster.

Tapping on the end helps make the water settle faster. Then take the readings from each post. Subtract the readings and you will get the distance in elevation between the two points. For instance, if the water level on one post is at the 19″ mark, and the water level on the other post is at the 7″ mark, then there is a 12″ difference in elevation between the two points. So easy!

If you are building swales on contour, keep moving one side of the bunyip until you find a spot where both readings are even, then mark those spots and repeat farther on. In this way you can find what land is level.

My daughter and I used our bunyip today to measure the change in elevation in our vegetable bed. We won’t be leveling the bed itself, but we will be digging deep, level swales, and we now know just how radically, and in which direction, our slope lies. This reaffirms what our eyes tell us about how rainwater flows across the veggie area and therefore how we’re to dig the swales to best catch rainfall.

Best of all, bunyips can be quickly disassembled and the parts used for other projects, or emptied and carried to other locations. Just add water, and you get a bunyip!

- Beverages, Breakfast, Fruit, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Recipes, Vegetarian

The Passion of the Fruit: Homemade Juices

Hi there. It’s Miranda the Guestblogger again, and today I want to talk to you about juice. You know, The Big Drip – Drosophilid Milk, Agua Fresca, Drupe’s Tears, Essence of Mesocarp: JUICE.

Here at Finch Frolic Garden, we like a nice fresh juice. As I am officially the FFG Harvester (a.k.a. Fruit Maven), I also take on the mantle of One Who Figures Out What To Do With Some Of The Stuff That’s Been Harvested – and let me tell you, that’s not a title to take lightly.

In the summer, it’s hard to keep up with all the produce and we hate to waste anything, even though spoilt food just goes back into the soil via compost here. We really like to get our produce into our mouths, though. Therefore, a lot of our fruit bounty gets juiced and frozen to keep. I want to walk you through some of our juiceplorations.

Finch Frolic Redoubtable Fruit of Almost Every Month in the Year: the Purple Passionfruit. These exotic and fragrant fruits are dropped by the bushel-load from our vigorous vines almost continuously, but overwhelmingly in midsummer. I pick them off the ground under the vines and wait for their smooth purple shells to wrinkle over in ripeness. Then the process begins.

I sit down for this and usually bring up a show on my laptop, because it takes a while. I have the bag or bowl of fruit on my right and a plastic bag looped over the back of a chair on the other side for the empty shells.

A fruit is picked up, dipped in a bowl of water, then wiped quickly on a paper towel and deposited on a cutting board that has a little rim on it to catch juice.

With a sharp knife, I halve the fruits and use a spoon to scoop the many little packets of bright gold-orange juice and hard black seeds into a bowl. Those packets have to be broken to get the juice.

I used to press the pulp into the mesh of a sieve with a spoon, but that’s hard on the hands and on the sieve. Now, I throw it in our Vita-Mix and turn it up to 3, tops – you want to spin all the juice off the seeds, but you don’t want to chop up the seeds. I judge whirl completeness by whether or not the little black seeds are free-floating as they sit in the mixture.

Then I run it through a sieve to separate out the juice.

To get the most juice out of it, you swirl a spoon through the pulp as it sits in the sieve.

All juiced out. This sounds very labour-intensive – and it is – but it’s worth it to us to use our fruit. We don’t eat passionfruit straight – the seeds are a little too gross. We do, however, use the juice in anything we can make an excuse to, and it keeps frozen into cubes for a long time. And the leftover seeds make a fun treat for our hens.

Glowing, beautiful, tangy, fresh passionfruit juice! In the fall, we’re overwhelmed with lovely big pomegranates from our one big pomegranate tree. This year, we’ve had more than ever and we didn’t want to waste any.

Once harvested, though, the poms need to be processed. Diane and I camped out every evening for a couple weeks cutting poms in half and hand-picking the arils. Recently, after a friend let us try out her juicer, we acquired one for ourselves, eliminating the need for the rest of the process with poms, but it is the same process I still use for grapes, apples and melons, so I’m going to tell you about it anyway.

I put the arils in the Vita-Mix and turn all the way up to completely blend the seeds. The blended pom also gets strained, but because the particles are finer than the passionfruit pulp, a mesh sieve isn’t sufficient. No, what you need is a sock.

A nice clean women’s nylon sock is perfect.

Hanging allows pure juice to come through. To get all the juice out, though, squeezing is necessary, and that puts a little more must in the juice, like fine fruit silt.

It’s also very taxing on the hands, because the sock must be hand squeezed, but it helps get the most juice from the fruit. This second straining produces interesting dry, crumbly must that comes out of the sock like purple Play-Doh.

Also a salutiferous treat for the hens! Like the passionfruit, we use the pom juice as much as we can. For instance, we reduced the juice and I experimented with some pomegranate ice-creams:

Chocolate makes an excellent palate cleanser, if you ask us. I also diluted the concentrate with water to make a lovely breakfast juice. We even poached pears with the juice for Christmas dinner – a lovely rose colour and delicate fruity flavor.

The fun never ends with fruit!

So, that’s a little peek at the juiceinations that go on here at Finch Frolic. Happy juicing to you!

TTFN!

Miranda the Fruit Maven

- Animals, Arts and Crafts, Chickens, Compost, Gardening adventures, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures

A Hen’s Garden

The girls helping prepare the soil before planting. Chickens are primarily bug eaters who also snack on greens. Feeding hens grains began with the industrialization of agriculture. No one cutting grain with a hand scythe would spend all that time and energy to feed hens.

My hens live in the Fowl Fortress, to protect them from coyotes and hawks (our hawks won’t be able to carry one away but they could tear them up pretty badly). After losing Chickpea to a coyote while we were only so many yards away made me eliminate any open foraging time for the girls. This wasn’t healthy for them. I haven’t invested in a solar electric fence yet, to make a ‘day’ coop for them to forage in relative safety, but that may be on my investment list for the new year. The largest problem is poor design in the garden, which I’m trying to remedy as easily and inexpensively as possible. I didn’t know how to fit in chickens, or where the garden was going when it began nearly three years ago. I have weedy areas, and I have chickens. To bring them together safely is the problem.

Sometimes we bring the hens into the fenced yard with our 100-pound African spur thigh tortoise (Gammera); however, that yard is also where some of our cats live. We’re not sure if Moose, Chester and Cody would behave themselves around hens, so unless we prevent the cats from leaving the house for the day, then we can’t carry the hens into this grassy yard to graze.

Inside the Fowl Fortress there is a layer of muck composed of old straw, the hard bits of veggies and fruit fed to the hens, old scratch and lots of chicken poo, made into an anaerobic muck by recent rains. Once turned up we discovered lots of the grain had sprouted, which the girls sucked up like noodles. This muck was also turning the hard ground below into prime soil. Why couldn’t we use this muck in a more productive manner?

If I couldn’t bring the hens to the garden, then I thought I’d bring the garden to them. Inside the Fowl Fortress I propped up four big boards in a square, then filled it with some of the rotting straw and muck from the coop. I topped it with Bermuda grass – laden soil from one of my raised beds. This was the bed, in fact, where I composted in place for the past year. What rich, chocolate-colored, worm-laden soil! If not for the invasive grass it would be perfect.

In this new garden, along with the Bermuda grass, my daughter and I planted oregano we divided from one of our plants, nettles, borage, some other kind of grass weeds that had sprung up after our Fall rain, plus we scattered corn and mixed organic grains which we feed the hens and pressed the seed into the ground.

The hens can graze, but can’t uproot the plants. Miranda wired together a bamboo lid out of scrap pieces. The idea is that the plants can grow up through the lattice of the bamboo lid and the hens can stand on it and eat greens. Oregano is a good medicinal herb, as are nettles, which reputedly encourage egg laying.

I also dig up chunks of weeds or Bermuda grass in this mercifully looser post-rain soil, and throw the whole mess into the Fowl Fortress and let the girls forage and exercise those strong legs by kicking through the heap. It is only logical that the strong kicking motion of foraging hens strengthens their bodies so that they have fewer egg-laying illnesses (egg-binding primarily), and of course their nutrition is much better with greens and bugs

This is by no means a permanent solution, but until I find the right design that keeps healthy, safe hens and eliminates weeds without a lot of work, then a chicken garden and weed-tossing is the way to go.