Animals

-

Fruit Flies – How To Be Rid of them Naturally

A jar, plastic and ACV. Works like a charm. It is fruit season and citrus and stonefruit are becoming ripe in the garden. When the fruit comes to the kitchen, and particularly when the peels and pits go into my open compost bucket, fruit flies appear as if by magic. It is amazing how quickly they show up and how quickly they reproduce. Fruit flies are busy laying eggs in any spot on any fruit or juice vegetable such as tomato. Gross. Here is a quick and inexpensive method of trapping and -unfortunately- killing the little things. I don’t like to kill anything, but I don’t know of a way to get around this, even when I drape towels over the fruit.

Take a small canning jar or baby food jar – something like that. Use the rim of the lid of a canning jar, or just a strong rubberband. You’ll also need a small piece of plastic to cover top of the jar; you can reuse some cellophane or part of an old plastic bag.

Fill the jar only about halfway with apple cider vinegar – not white distilled vinegar. Place the plastic over the top and secure with the lid rim or a rubber band.

A fruit fly finding a way in. Take a toothpick and prick tiny holes in the plastic. Set the jar near where the fruit flies accumulate and forget about it. Be sure to remove other lures such as old kitchen scraps or fruit, or cover it with dishtowels. That’s that. The flies swarm to the jar and eventually disappear into it and can’t get out.

A kind of blurry photo of lots and lots of fruit flies queuing up to get inside. - Animals, Birding, Chickens, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Humor, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Photos, Ponds, Reptiles and Amphibians

Happy Easter!

Heirloom irises from my good friend Jean are blooming.

A Western fence lizard suns and guards his territory atop a clary sage leaf. See the flash of blue under his chin to attract the ladies?

This green calla lily is gorgeous.

Framed by curly willow from the Withy Bird Hide, two drakes swim in the pond on Easter morning.

Sweet peas are still blooming. They hold the permaculture precept of everything having three purposes: they are nitrogen fixers, they are edible, and they are gorgeous.

A fancy drake who showed up this morning.

The irises surrounding the pond are spectacular right now. Blue, dark blue and yellow flag.

Baby bunny has been growing out his ears. He’s enjoying a warm dirt bath.

Mulan has gone broody. Such a large chicken puddles out over the wooden egg she’s trying to hatch. We’re feeding her an oatmeal mixture in a dish because she won’t come down during the day.

Easter breakfast. Hard boiled eggs, naturally colored by our hens, fresh tangerine juice, our traditional stollen from my mother’s recipe, and Peanut in his chicky robe ready to launch into the food. Peanut doesn’t act his age, of about 40+ years, but has traveled and been photographed extensively in Europe and Ecuador. Its nice that he wakes up for holidays. - Animals, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Soil, Water Saving

Actively Aerated Compost Tea

Aerator, molasses, a paint strainer full of compost and a bucket of water. There are many teas for the garden. Manure tea is made by steeping… you guessed it… well-aged manure in water for several days. Well-aged is the key. Many years ago I gathered horse manure, made a tea and righteously spread it – and all the Bermuda grass seed that was in it – all over my vegetable garden. I’m still battling the grass. With fresh manure you are also brewing some nasty bacteria with which you really shouldn’t be dealing. Allowing well aged or composted manure to brew for a couple of days will produce a nice nutrient tea for your plants. There are better brews for your effort.

Plain compost tea is when you take samples of good soil and allow them to steep in water for several days and use that. This brew has some microbes and basic nutrients in it and is better than plain water for enhancing your soil and as a foliar spray.

However there is a super brew called actively aerated compost tea. It is very simple and inexpensive to make and it works wonders. There are many recipes for it, depending upon how analytical you want to become. Studying your soil under a microscope and following the advice of Dr. Elaine Ingham will give you the premium tea for your particular soil. Dr. Ingham and Dr. Carole Ann Rollins have many books out on the subject of microorganismsin the soil which are all fascinating and well worth the read; if you ever have the chance to hear Dr. Ingham speak, take it!

I don’t tinker with my tea at this time because I just don’t have the time for it. You may not, either. So this is the basic aerated compost tea recipe that will revitalize your soil:

You will need a 5-gallon bucket, a paint strainer or cheesecloth or an old sock, a fish tank aerator or air bubbler, and one or all of these: organic unsulphered molasses, organic flours, organic corn meal, kelp. I have had excellent luck with TeaLab’s Bubblesnake Compost Tea Brewer. I don’t get anything for the plug, I just found that the kit really works and is easy to buy. I purchased through AmazonSmile.

Fill the bucket with either rainwater or tapwater that has stood for at least a day for the chlorine to have evaporated.

Take the paint strainer or sock and fill it with samples of good soil from around your property. If you don’t have any good soil, then add the best you have and then take good soil from areas as close to your property as possible. If you will be using the tea on bushes and trees, then be sure to take soil from under the same. Woody plants like highly fungal soil. If you will be using the tea for annuals and veggies, then go heavy on fine, well-composted soil that is bacteria-rich. Do the best you can; you can’t go wrong unless you take soil that has been sprayed with chemicals, use treated wood chips, or anaerobic soil (you’ll smell it if you do).

Tie the top of the cloth and put it into the bucket. You may tie twine or something around it so that you can haul it out of the bucket if you’d like. This is important on larger containers, but not so much with the small bucket.

Place the aerator or bubbler in the bucket, making sure the air intake hose is clear, and plug it in.

Add about a half tablespoon of molasses. It is important that the molasses is unsulphered and organic for the same reasons that the water shouldn’t have chlorine in it or the soil any chemicals: those things will hurt the microbes that you will be growing. For growth of other microbes, add about a teaspoon of any or all of the following: organic cornmeal, organic wheat flour, liquid kelp, and if you have it tucked away in your shed, bonemeal and bloodmeal (otherwise don’t buy it specially!). So the more different foods you add, the less of each that you use. Two tablespoons of food is about all you want; don’t have a big glob of it floating in your bucket.

Allow the aerator to do its thing for about 13 hours. When its done it should look and smell like sweet tea. Use it within a couple of hours or the creatures will use up all the oxygen and it will go bad. There is much discussion about how long you brew it, etc., just as there are hundreds of stew recipes. This is the recipe taught me in my PDC and one I’ve heard elsewhere. If your tea smells bad, any hint of ammonia or ‘off’ smells, don’t apply it to your plants. You’ll be hurting them. Be sure you have good compost, fresh water and proper aeration, and don’t let it sit too long.

What you are making is not just tea, it is soil inoculant. The micororganisms in the compost will feed on the molasses and oxygen, reproducing until at about 13 hours their numbers will peak and begin dying off a little. The tea should be used within a couple of hours.

Brew the tea for 13 hours then gently apply as a soil drench or foliar spray. What this tea is doing when applied, is establishing or boosting the fungus, bacteria, amoebas, nematodes, and other soil inhabitants in your dirt, all of which are native to your particular area. If you have decent soil already, then you can use this tea 1:10 parts dechlorinated water. If you have rotten dirt, use it straight along with a topping of compost. Compost, whether it be cooked composed compost, straight leaf matter, shredded wood, logs, damp cardboard or natural fabrics, all provide shelter and hold moisture in so that your microbes have habitat. Compost, of course, is the best source of food, moisture and shelter for them.

Apply the tea with a watering can, or a sprayer that has a large opening for the nozzle if you are using the tea as a foliar spray. A squeeze-trigger bottle used for misting has too narrow an opening and will kill a lot of the little guys you have just grown.

Using the tea as a foliar spray will treat disease, fungus and nutrient deficiencies, and help protect plants against insect attack. Instead of spraying sulfur or Bordeaux solution on your trees as is preached by modern gardening books, use compost tea on the leaves and around the drip line. When applied to leaves, the plant’s exudates hold the beneficial microorganisms to the stomata or breathing holes protecting them from disease and many harmful insects. You can’t overdose with compost tea.

All the additives that are recommended to ‘improve’ your soil are bandages not solutions. Think of the billions of soft-bodied creatures living in your soil, waiting for organic matter to eat. Then think of the lime, the rock dusts, the gypsum, the sulfur, the NPK concentrated chemical fertilizers (even derived from organic sources), poured onto these creatures. It burns them, suffocates them and kills them. Your plants show some positive results to begin with because they’ve just received a dose of nutrients, both from what you applied and from the dead bodies of all those murdered microbes. However the problem still is there. The only long-term solution to locked-up nutrients in the soil, hard pan, heavy clay, sand, compaction, burned, or poisoned soil, is good microbe-filled compost. Remember that microbes turn soil into a neutral pH, and allow more collection of neutral pH rainwater. Nutrients in the soil all become available at a neutral pH; there is no such thing as an iron-deficient soil. The nutrients are just locked away from the roots because of the lack of microbes and the pH.

There are compost tea brewers of all sizes, and lots of discussion about how well they work and whether they actually kill off a lot of microbes. See Dr. Elaine Ingham’s work for discussion on different brewers. For large scale operations there are large tanks with aggressive aerators, and the tea is sprayed from the tanks from a truck bed directly on the fields. If you can’t compost your entire property, then spraying compost tea is the next best thing.

If you’d like to be more involved with the biology of your tea, see Qualitative Assessment of Microorganisms by Dr. Elaine Ingham and Dr. Carole Ann Rollins. This book has photos of different soil components as they appear under a microscope, identifying and explaining them. By studying your soil’s balance through a microscope and then tweaking your tea to compensate you’ll be making the most powerful soil inoculant you can.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Chickens, Cob, Compost, Composting toilet, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hiking, Humor, Living structures, Natives, Natural cleaners, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Photos, Ponds, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving, Worms

Finch Frolic Facebook!

Thanks to my daughter Miranda, our permaculture food forest habitat Finch Frolic Garden has a Facebook page. Miranda steadily feeds information onto the site, mostly about the creatures she’s discovering that have recently been attracted to our property. Lizards, chickens, web spinners and much more. If you are a Facebook aficionado, consider giving us a visit and ‘liking’ our page. Thanks!

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fruit, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Herbs, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

The Mulberry Guild

The renovated and planted mulberry guild. One of our larger guilds has a Pakistani mulberry tree that I’d planted last spring, and around it had grown tomatoes, melons, eggplant, herbs, Swiss chard, artichokes and garlic chives.

Mulberry guild with last year’s plant matter and unreachable beds. This guild was too large; any vegetable bed should be able to be reached from a pathway without having to step into the bed. Stepping on your garden soil crushes fungus and microbes, and compacts (deoxygenates) the soil. So of course when I told my daughter last week that we had to plant that guild that day, what I ended up meaning was, we were going to do a lot of digging in the heat and maybe plant the next day. Most of my projects are like this.

Lavender, valerian, lemon balm, horehound, comfrey and clumping garlic chives were still thriving in the bed. Marsh fleabane, a native, had seeded itself all around the bed and had not only protected veggies from last summer’s extreme heat, but provided trellises for the current tomatoes.

Fleabane stalks from last year, with new growth coming from the roots. Marsh fleabane is an incredible lure for hundreds of our tiny native pollinators and other beneficial insects. Lots of lacewing eggs were on it, too. The plants were coming up from the base, so we cut and dropped these dead plants to mulch the guild.

The stalks of fleabane are hollow… perfect homes for small bees! The stems were hollow and just the right size to house beneficial bees such as mason bees. This plant is certainly a boon for our first line of defense, our native insects.

We also chopped and dropped the tomato vines. Tomatoes like growing in the same place every year. With excellent soil biology – something we are still working on achieving with compost and compost teas – you don’t have to rotate any crops.

Slashed and dropped tomato and fleabane. We had also discovered in the last flood that extra water through this heavy clay area would flow down the pathway to the pond, often channeled there via gopher tunnels.

The pathway is a water channel during heavy rains. It needs fixing. We decided to harvest that water and add water harvesting pathways to the garden at the same time. We dug a swale across the pathway, perpendicular to the flow of water, and continued the swale into the garden to a small hugel bed.

Swale dug on contour through the pathway and across the guild. Hugelkultur means soil on wood, and is an excellent way to store water in the ground, add nutrients, be rid of extra woody material and sequester carbon in the soil. We wanted the bottom of the swale to be level so that water caught on the pathway would slowly travel into the bed and passively be absorbed into the surrounding soil. We used our wonderful bunyip (water level).

Using a bunyip to make the bottom of the swale level. Water running into the path will now be channeled through the guild. Because of the heavy clay involved we decided to fill the swale with woody material, making it a long hugel bed. Water will enter the swale in the pathway, and will still channel water but will also percolate down to prevent overflow. We needed to capture a lot of water, but didn’t want a deep swale across our pathway. By making it a hugel bed with a slight concave surface it will capture water and percolate down quickly, running along the even bottom of the swale into the garden bed, without there being a trippable hole for visitors to have to navigate. So we filled the swale with stuff. Large wood is best for hugels because they hold more water and take more time to decompose, but we have little of that here. We had some very old firewood that had been sitting on soil. The life underneath wood is wonderful; isn’t this proof of how compost works?

The activity under an old log shows so many visible decomposers, and there are thousands that we don’t see. We laid the wood into the trench.

Placing old logs in the swale. If you don’t have old logs, what do you use? Everything else!

This giant palm has been a home to raccoons and orioles, and a perch for countless other birds. The last big wind storm distributed the fronds everywhere. We are wealthy in palm fronds.

Three quick cuts (to fit the bed) made these thorny fronds perfect hugelbed components. We layered all sorts of cuttings with the clay soil, and watered it in, making sure the water flowed across the level swale.

We filled the swale with fronds, rose and sage trimmings, some old firewood and sticks, and clay. As we worked, we felt as if we were being watched.

Can you spot the duck in this photo? Mr. and Mrs. Mallard were out for a graze, boldly checking out our progress. He is guarding her as she hikes around the property, leading him on a merry chase every afternoon. You can see Mr. Mallard to the left of the little bridge.

This male mallard and his mate, who is ‘ducked’ down in front of him, enjoyed grazing on weeds and watching we silly humans work so hard. After filling the swale, we covered the new trail that now transects the guild with cardboard to repress weeds.

Cardboard laid over the hugelswale. Then we covered that with wood chips and delineated the pathway with sticks; visitors never seem to see the pathways and are always stepping into the guilds. Grrr!

The cardboard was covered with wood chips and the pathway delineated with sticks. Where the trail curves to the left is a small raised hugelbed to help hold back water. At this point the day – and we – were done, but a couple of days later we planted. Polyculture is the best answer to pest problems and more nutritional food. We chose different mixes of seeds for each of the quadrants, based on situation, neighbor plants, companion planting and shade. We kept in mind the ‘recipe’ for plant guilds, choosing a nitrogen-fixer, a deep tap-rooted plant, a shade plant, an insect attractor, and a trellis plant. So, for one quarter we mixed together seeds of carrot, radish, corn, a bush squash, leaf parsley and a wildflower. Another had eggplant, a short-vined melon (we’ll be building trellises for most of our larger vining plants), basil, Swiss chard, garlic, poppies, and fava beans. In the raised hugelbed I planted peas, carrots, and flower seeds.

In the back quadrant next to the mulberry I wanted to trellis tomatoes.

This quadrant by the mulberry needed a trellis for tomatoes. I’d coppiced some young volunteer oaks, using the trunks for mushroom inoculation, and kept the tops because they branched out and I thought maybe they’d come in handy. Sure enough, we decided to try one for a tomato trellis. Tomatoes love to vine up other plants. Some of ours made it about ten feet in the air, which made them hard to pick but gave us a lesson in vines and were amusing to regard. So we dug a hole and stuck in one of these cuttings, then hammered in stakes on either side and tied the whole thing up.

Tying the trunk to two stakes with twine taken from straw bales. Love the blue color! The result looks like a dead tree. However, the leaves will drop, providing good mulch, the tiny current tomatoes which we seeded around the trunk will enjoy the support of all the small twigs and branches, and will cascade down from the arched side.

The ‘dead tree’ look won’t last long as the tomatoes climb over it and dangle close to the path for easy harvesting. We seeded the area with another kind of carrots (carrots love tomatoes!) and basil, and planted Tall Telephone beans around the mulberry trunk to use and protect it with vines. We watered it all in with well water, and can’t wait to see what pops up! We have so many new varieties from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds and other sources that we’re planting this year! Today we move onto the next bed.

-

The Fine Art of Pleaching or Plashing

Pleaching in the sky. My daughter and I pleached today, although I’ve had the pleasure of pleaching before this , and even later. Pleaching, or its synonym plashing, refers to the interweaving of branches, both live or dead. Basketry is one form, but more notably is the pleaching of living branches to form secure living fences, buildings or artwork. The withy (willow) bird hide (a covered place from which to watch birds) is a living building I planted two years ago. We pleached our withy hide today. Not many people can say that! (or admit to it).

Pleaching is where stems, usually from two plants, grow together. Pleaching can be done on many vigorous trees such as willow, or even fruit trees such as plum. The branches grow together making separate plants become part of a whole. The trees then share nutrients and water and can pull what it needs from roots a long distance away.

Curly willow is beautiful on its own. Pleaching essentially makes many plants into one living organism. Pleached hedgerows make a living barrier to keep in livestock; pleached trees can be woven into furniture, living artwork, decorative fences, and living trellises. Pleaching livestock fences was practiced a lot in Europe prior to the invention of barbed wire, and then was forgotten for awhile only to be revived as a form of artistic gardening.

This trunk unfortunately cracked while I pulled on it. As it is willow, it will heal quickly. My daughter used the opportunity to put a twig from the next willow through the crack, which will grow over it. Today I of course, as is my habit, waited until the sun was directly above the area where I was working so that I had to look into it as I worked. I don’t recommend this, however. My daughter used a fruit-picking pole to snag some of the taller, whippier branches of the curly willow that make up the withy hide. I stood on a ladder, squinting, and pulled two branches together.

Me on a ladder reaching over my head to pull two branches together to form a roof. To insure that you have a good pleach going, it is best to lightly scrape the bark from both pieces just where they are going to meet; something like you see blood brothers do with their hands in the movies, but with no blood involved.

Lightly scraping the bark from both branches where they will meet is important. Next time I’ll use a vegetable peeler, which will allow me better angles. Then you make sure the pieces fit snugly, then tie them on. I’ve use various materials to do this. Twist-ties hold securely but the wire can eventually girdle the growing branches. Twine is more difficult to use in that it doesn’t grip the branches well enough for a firm hold, but it will eventually break down, hopefully after the pleach is successful. This time I used green tree tape. It grips well, is easy to tie, and will stretch with the growing branches and eventually break. The green color won’t be noticeable when the willow leafs out, either.

Tying the scraped branches together so they stay put. They can’t move around in the wind or they won’t be able to grow together. As I pleached from the top of the ladder, working overhead while the sun and curly twigs attacked my eyes, my daughter pleached pleasing arches over the ‘windows’ of the hide.

Weaving curly willow can be a twisty challenge. The hide looks lopsided because the willows on one side have found sent out roots to drink from the small pond. With more pleaching, the thirsty trees on the other side will probably take advantage of that water source, too, and have a drink via their overhead connection. I think it is part of its charm. A half-wild building.

The withy hide as a duck on the big pond sees it. The willow is just about to begin leafing out. Try pleaching a small fence or a living bench or chair. It is tremendous fun and if you don’t like it, you can always cut it down. Oh, and work on a cloudy day.

A willow roof. - Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

Planting Spores in the Garden

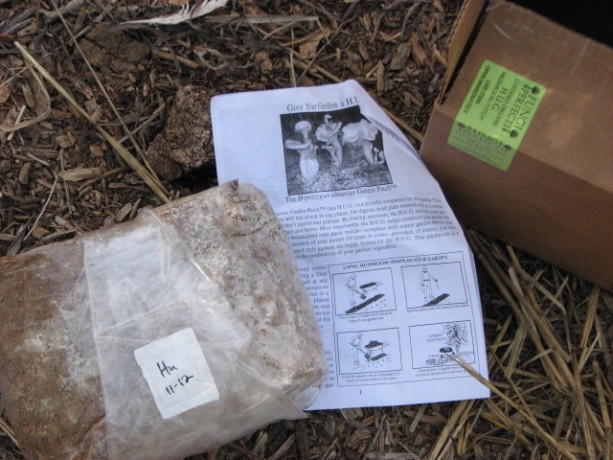

The mycelium is white in the sawdust and ready to go. If you remember the trenching, filling and designing the new veggie patch, then this post will make more sense to you.

The next step was to cardboard the pathways where Bermuda grass has been taking over, then mulch them as well. The mulch makes it all look so nice!

Covered with mulch, the cardboard is only a memory. Next it was time to plant. We’d already transplanted three-year old asparagus, and hopefully not shocked them so much that they won’t produce well this year. The flavor of fresh asparagus defies description.

Asparagus popping up some feather shoots from its new home. The strawberry bed was older and completely taken over by Bermuda grass, so it all was buried and I purchased new organic and extremely reasonably priced bareroot strawberries.

A bundle of twenty-five strawberries. I purchased two June-bearing types and three ever-bearing, heat-loving types, from www.groworganic.com. When they bloom this year we’ll have to nip off the buds so that next year when their roots have taken hold and fed the crown, we can have lots of strawberries.

Soaking the strawberry roots for a few minutes rehydrates them. We planted some in the asparagus bed, which will do nicely as groundcover and moisture retention around the asparagus, while the asparagus keeps the heat off the strawberries. Some we planted around the rock in the center of the garden. The rest will be planted around fruit trees as part of their guilds.

Strawberries surround the rock. We also planted rhubarb in the asparagus bed; these poor plants had been raised in the greenhouse for several months awaiting transplanting.

Rhubarb, really eager to be put in the ground. Hopefully the asparagus will protect them from the heat. I plan to raise more rhubarb from seed and plant them in other locations on the property, aiming for the coolest spots as they don’t like heat at all.

With a strong knife (weak blades may snap) cut a cross in wet cardboard the pull aside the edges. The way to plant through cardboard is to make sure that it is wet, and using a strong knife make an x through the cardboard. Use your fingers to pull the sides apart. Stick your trowel down and pull up a good shovel full of dirt (depending on how deeply your plant needs to go.

Insert a trowel through the hole and scoop out some dirt. The base of plants and the crowns of strawberries should all be at soil level. Seeds usually go down three times their size; very small seeds may need light to germinate). Gently plant your plant with a handful of good compost, then water it in. You won’t have to water very often because of the mulch, so check the soil first before watering so that you don’t overwater.

Don’t forget to water in the plants! For the first time in years I ordered from the same source Jerusalem artichokes, or Sunchokes as they’ve been marketed. They are like sunflowers with roots that taste faintly like artichoke. We planted some of them in one of the quadrants, and the rest will be planted out in the gardens, where the digging of roots won’t disturb surrounding plants.

The oyster mushroom kit, or H.U.G. You’ll have to visit Fungi Perfecti to read up on it. Most excitingly, we’ve purchased mushroom spores from Fungi Perfecti, which is Paul Stamet’s business, the man who wrote Mycelium Running and several other books about growing mushrooms for food and for health. We bought inoculated plugs, but that will be another post. Almost as exciting are the three bags of inoculated sawdust to spread in the garden! They sell an oyster mushroom that helps digest straw and mulch, while boosting the growth of vegetables and improving the soil. You also may be able to harvest mushrooms from it! Talk about a wonderful soil solution, rather than dumping chemical fertilizers on the ground!

We’d already covered our veggie beds with wet cardboard and straw.

Really good soil from what is now a mulched pathway. To give the mycelium a good foundation I dug up good soil from one of the field beds, which needed an access path through the middle. By digging out the path I created new water-holding swales, especially when filled with mulch.

We pulled aside the straw. In the veggie garden we raked back the straw and lightly topped the wet cardboard with soil. On top of that we sprinkled the inoculated sawdust.

Good soil over cardboard. On top of that we pulled back the straw and watered it in.

Sprinkling spore-filled sawdust over the soil. The fungus will activate on the wet soil, eat through the cardboard to the layers of mushroom compost and pidgin poo underneath that and help make the heavy clay beneath richer faster.

The fungi will immediately begin to colonize the wet soil. We treated the two top most beds which have the worst soil, the sunchoke bed and the asparagus bed. In four to six weeks we may see some flowering of the mushrooms, although the fungus will be working even as I sit here. There are several reasons why I did this. One, it is just totally cool. Secondly, there is no way for me to purchase organic straw. By growing oyster mushrooms in it, I’m hoping the natural remediation qualities of the oyster fungus will help cleanse the straw as it decomposes. Oyster mushrooms don’t retain the toxins that they remove from soil and compost, so the mushrooms will still be edible. Fungus will assist rebuilding the soil and give the vegetables a big growing boost. I know I’ve preached that vegetables like a more bacterial soil rather than fungal. This is true, except that there are different types of fungus. If you put wood chips in a vegetable bed, you’ll activate other decomposing fungus that will retard the growth of your tender veggies; the same wood chips around trees and woody plants will help them grow. However these oyster mushrooms will benefit your veggies by quickly decomposing compost and making the nutrients readily available to the vegetables. Their hyphae will help the veggie’s roots in their search for water and nutrients, too.

Straw is over the top and watered. We can continue to plant in the beds as the fungus does its magic. The other two bags of inoculated spores are for shaggy mane and garden giant, which we’ll find homes for in compost under trees. More on that as we progress. It is so nice to be planting, especially since these are perennial plants where the most work is being done now. Now we just need some rain!

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Pets, Rain Catching, Soil, Worms

The Sunken Bed Project, Part Two

Old wire can be buried! Remember the trenches? We lined the trenches with old rusty wire, to rot, add iron to the soil, and discourage rodents. Mostly just to get rid of it. Inside the wire we lay old wood; in this case, the half-rotten sides of the old raised beds, nails and all. Fabric can be buried, too! Pet bedding no longer fit for man nor beast. Except for microbes of course. Around the wood we packed old fabric, most of which had been dog or cat bedding after long use in the house. There was also this futon! It had been a bed for years, and then it was the bed for the dogs for years. And for some mice. It took a little cutting and pulling to separate the cotton batting and the foam. Although the foam isn’t made from a natural material, it will eventually rot, but meanwhile will function like a ginourmous buried sponge for rainwater! The futon slices layed in the trench. Yipee! The stinky old futon is gone! Lots of branches, twigs, and woody materials were added, as was some year-old humanure, urea, and fallen limes. Nasty prickly lime tree branches, too. Serves them right for scratching me! After layering the trench materials with soil I used palm fronds for the top organic layer. Every step was watered in. Our 700-gallon water tank, formerly an organic fertilizer tank which Jacob managed to have donated, catches some of the roof rainwater. It has more than enough to water in this project, and then if it ever rains again the tank will be empty and ready for fresh water. The trenches filled in. Futons, scrap wood, woody bits, old stinky fabrics, manure… its all buried and ready to turn the clay into a microbial wonderland. We hauled chunks of extra clay up the hill and staged it by the upper pond, which needs to be resealed. Good leg exercise. The long hugelkultur strawberry bed was above ground, so it had to be reworked. We dug out the wood, wrestled out the wire, dug down about a food then lay the wire back down. There were gopher tunnels under the wire where they had come up and smashed their little noses against the wire. The wood that had been buried for a year was full of life! There were many very cool fungi. Tiny centipede-type decomposers eating away at the wood, all of which had been underground. More great fungus. On top of the wire went some more old textiles, then most of the old wood. Bunches of herbs that had been gathered for wreathes and not used were tucked in around the wood. Worms love thin woody stuff. Pigeon guano, thanks to our neighbor who delivers, was sprinkled over it all. Everything was well watered with rainwater, and then covered up. Next time: design, replanting asparagus, and perhaps even the final product! - Animals, Arts and Crafts, Chickens, Compost, Gardening adventures, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures

A Hen’s Garden

The girls helping prepare the soil before planting. Chickens are primarily bug eaters who also snack on greens. Feeding hens grains began with the industrialization of agriculture. No one cutting grain with a hand scythe would spend all that time and energy to feed hens.

My hens live in the Fowl Fortress, to protect them from coyotes and hawks (our hawks won’t be able to carry one away but they could tear them up pretty badly). After losing Chickpea to a coyote while we were only so many yards away made me eliminate any open foraging time for the girls. This wasn’t healthy for them. I haven’t invested in a solar electric fence yet, to make a ‘day’ coop for them to forage in relative safety, but that may be on my investment list for the new year. The largest problem is poor design in the garden, which I’m trying to remedy as easily and inexpensively as possible. I didn’t know how to fit in chickens, or where the garden was going when it began nearly three years ago. I have weedy areas, and I have chickens. To bring them together safely is the problem.

Sometimes we bring the hens into the fenced yard with our 100-pound African spur thigh tortoise (Gammera); however, that yard is also where some of our cats live. We’re not sure if Moose, Chester and Cody would behave themselves around hens, so unless we prevent the cats from leaving the house for the day, then we can’t carry the hens into this grassy yard to graze.

Inside the Fowl Fortress there is a layer of muck composed of old straw, the hard bits of veggies and fruit fed to the hens, old scratch and lots of chicken poo, made into an anaerobic muck by recent rains. Once turned up we discovered lots of the grain had sprouted, which the girls sucked up like noodles. This muck was also turning the hard ground below into prime soil. Why couldn’t we use this muck in a more productive manner?

If I couldn’t bring the hens to the garden, then I thought I’d bring the garden to them. Inside the Fowl Fortress I propped up four big boards in a square, then filled it with some of the rotting straw and muck from the coop. I topped it with Bermuda grass – laden soil from one of my raised beds. This was the bed, in fact, where I composted in place for the past year. What rich, chocolate-colored, worm-laden soil! If not for the invasive grass it would be perfect.

In this new garden, along with the Bermuda grass, my daughter and I planted oregano we divided from one of our plants, nettles, borage, some other kind of grass weeds that had sprung up after our Fall rain, plus we scattered corn and mixed organic grains which we feed the hens and pressed the seed into the ground.

The hens can graze, but can’t uproot the plants. Miranda wired together a bamboo lid out of scrap pieces. The idea is that the plants can grow up through the lattice of the bamboo lid and the hens can stand on it and eat greens. Oregano is a good medicinal herb, as are nettles, which reputedly encourage egg laying.

I also dig up chunks of weeds or Bermuda grass in this mercifully looser post-rain soil, and throw the whole mess into the Fowl Fortress and let the girls forage and exercise those strong legs by kicking through the heap. It is only logical that the strong kicking motion of foraging hens strengthens their bodies so that they have fewer egg-laying illnesses (egg-binding primarily), and of course their nutrition is much better with greens and bugs

This is by no means a permanent solution, but until I find the right design that keeps healthy, safe hens and eliminates weeds without a lot of work, then a chicken garden and weed-tossing is the way to go.

-

Good-bye, Sweet Belle: The Death of a Crossbill Hen

Belle in her bath. Last Tuesday when I opened the chicken tractor to let the girls come bounding and clumsily flutter out for their breakfast, Belle our genetic crossbill Americauna didn’t emerge with her usual energy. I make a custard of blended chicken food, whole eggs, greens and fruit, cooked and cooled, to feed her. The custard contained all the goodies the other hens had, but was easier for her to scoop with her twisted beak. I’d fill her dish before I come down to ‘do the hens’, and she was fed first. Her dish was placed into the top of the quail hut with the door propped open so only Belle coud get in and out; the other hens loved to share her food otherwise.

Although Belle ate vigorously, she never gained full body weight. Her beak prevented her from eating well enough. Out of every five scoop attempts at the custard I’d say that she’d get one mouthful. Yet she was always perky, always running around interested in everything, and even tried dominance tactics over some of the other girls. They’d let her since she wasn’t a threat to any of their food.

Because Belle’s eating habits were very messy her neck and head feathers were straggly, and combined with her twisted beak gave her a comical, slightly crazed look. Because she was handled so much when she patiently allowed us to trim her beak and nails, and give her a bath, she was very friendly. She’d jump on our backs and shoulders any time we’d bend over in the coop. She’d enjoy being carried around. She was very spoiled. We’d read posts where owners of crossbills, who didn’t cull them but kept them as pets, had them live up to ten years and lay eggs. It was all dependant upon to what degree their bills crossed, and Belle’s became severe.

About a month ago we noticed mites on her, something that is common on hens, and gave her a good bath and treatment with food grade diotomaceous earth. The FGDE works immediately and is very effective and safe. Otherwise she was bright, fun and perky, burrowing under the other girls on the roost overnight to cuddle.

Tuesday Belle was slower to come around, and didn’t want to eat. A hungry hen not wanting to eat? Bad news. We immediately took her into the house. It was a cold day, so we made her comfortable next to a space heater. On inspection we discovered that she had mites all over her. We also checked the other hens right away and they were all okay, so apparently Belle’s diminishing health encouraged them to reproduce, and as she couldn’t groom herself she was stuck. We coated her with FGDE, not wanting to bathe her while she was feeling poorly since it was a cold day, and dropper fed her food. She showed some energy and wanted to run around, and took the food hungrily.

It was time to trim the Christmas tree, and my daughter put Belle under her sweater to keep her warm and comforted as we worked; Belle loved being cuddled and held, so she put up no resistance, but we could see that she was ill.

We brought in the cage that we used for Viola the ex-house chicken, and for all of our patients, and tucked Belle in for the night next to the space heater.

In the morning Belle was sitting very still. I knew that she was nearly gone. Just after waking my daughter, Belle died as she held her. She is buried outside our bay window where we watch birds, close to the house.

Belle usually can’t wait until she’s served. Birds are so tricky. They can seem perfectly fine, but when they show illness it is usually too late and the end comes quickly. There is little you can do for them besides keep them comfortable. Neither of us expected Belle to pass away; she showed no previous symptoms and was her usual plucky, fun self. Something internal gave way from slow malnutrition caused by that darned crossed bill and her inability to eat enough. On reflection I don’t think that Belle had a bad life. She ate enough to not be hungry all the time, and her custard gave her ease of eating. She was much loved and spoiled. Her end was quick, which was merciful and not granted to many of us. But Belle will always be remembered.

Ah haz a friend!