Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants

In the last post we explored one way plants take nitrogen out of the air and fix it in the soil. Now we’ll explore how plants take nutrients from deep in the soil and deliver them to the soil surface. This is another way that plants create high nutrient topsoil.

All rooted plants gather nutrition from the soil, store it in their leaves, flowers and fruit, and then create topsoil as these products fall to the ground. Every plant is a vitamin pill for the soil. When you pull ‘weeds’, clear your garden, prune and otherwise amass greenery and deadwood, you are gathering vitamins and minerals for your soil. Bury it. All of it. If its too big to bury, then chip it and use it as top mulch. Allow that nutrition to return to the soil from whence it came. No stick or leaf should leave your property! Period.

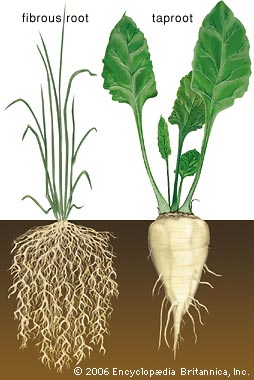

There are mainly two kinds of root systems: fibrous (like many grasses) and taprooted. Some taprooted plants grow very deeply. Those plants that are deemed ‘mining’ plants go the extra mile. I envision mining plants as the gruff gentlemen of the plant guild: tough and weathered, dressed in pith helmet and explorer clothes with a larger-than life character and a heart of gold.

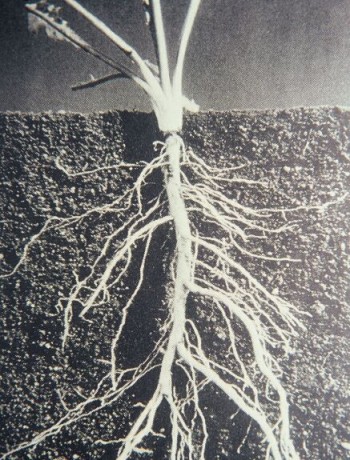

Okay, too many old movies on my part. The roots of mining plants are large taproots that explore the depth of the soil searching for deep water. Depending upon the size of the plant, these roots can break through hardpan and heavy soils. They create oxygen and nutrient channels, digging tunnels that weaker roots from less bold plants and soft-bodied soil creatures can follow. When these large roots die they decompose deep in the ground, bringing that all-important organic material into the soil to feed microbes. Meanwhile these Indiana Jones’s of the root world are finding pockets of minerals deep in the soil – far below the topsoil and where other roots can’t reach – and are taking them into their bodies and up into their leaves. When these leaves die off and fall to the ground they are a super rich addition to the topsoil. Often the deep taprooted plants have a sharp scent or taste. Many weeds found in heavy soils are mining plants, sent by Mother Nature to break up the dirt and create topsoil. Dicotyledonous (dicot) plants have deep taproots, if you are into that kind of thing. The benefits of a plant having a deep taproot is not only to search for deep water, but to store a lot more sugar in the root, be anchored firmly, and to withstand drought better.

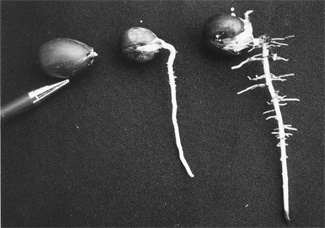

So who are these helpful gentlemen adventurers of the plant guilds? Comfrey and artichoke are two commonly used mining plants. Also members of the, radish, mustard, and carrot family such as, parsnip, root celery, horseradish, burdock, parsley, dandelion, turnip, and poppy to name a few. There is also milkweed (Asclepias), coneflower, chicory, licorice, pigeon pea, and for California natives there is sagebrush, Matilija poppy, oaks, mesquite, Palo Verde and many more. Most deep taprooted plants don’t transplant well because their straight taproot is often much longer than the top of the plant. Check out a sprouted acorn. The taproot is many times as deep as the top is high.

Yet some mining plants such as comfrey and horseradish can be divided or will sprout from pieces of the root left in the ground. Deep taprooted weeds seem to all be like that, at least on my property!

Now for a little comfrey prosthelytizing: Comfrey keeps coming back when chopped, so it is often grown around fruit producing trees to be chopped and dropped as a main fertilizer. Its leaves are so high in nutrition that they are a compost activator, an excellent hen and livestock food (dried it has 26% protein), and have been heavily used in traditional medicine. Also called Knitbone, the roots contain allantoin, a substance also found in mother’s milk, which among other benefits helps heal bone breaks when applied topically.

The plant also has flowers that bees and other insects love. It spreads by seeds as well as divisions, and non-permaculture gardeners don’t like it escaping in their gardens. I only wish that mine would spread faster, to create more fertilizer. Comfrey grows the best greens with some irrigation and better soil, so it is perfect for use around fruit trees.

So when planting a guild you can easily plant miners that are edible. If you harvest those deep taproots, such as carrots or parsnips, then be sure to trim the greens and let them fall on the spot, so the plant will have done its full duty to the soil. Unless the plant can take division, such as the aforementioned comfrey, then planting seeds are best. Deep taprooted plants in pots are often stunted and either don’t survive transplanting well, or will take a long time to grow on top because they need to grow so much on the bottom first.

Next up: the exciting groundcover plants!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

3 Comments

PARAG SHAILENDRA JADHAV

Thanks For Writing. Its very helpfull, Thanks for Sharing.

Pigeon Pea

Diane

Joe, how on earth did that happen? I just fixed it. Thanks so much for reading, for catching the error, and especially for your kind comments. I’m really glad that I can help. With desertification occurring there are more resources out there for you to go to than there ever has been. On the Resources page of this blog I list books that I’ve read and recommend (there are many more I haven’t read yet), and there are several on dryland permaculture that are very good. Best wishes for great success on your food forest project! Thanks again, Diane

Joe

You forgot your links on this page to the next post! Thank you for writing, I am just getting started transforming my urban desert property into a food forest. This is one of the best resources on building guilds that I have encountered!