- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants

Artichokes are mining plants, but also have a low enough profile to be a groundcover plant. They make excellent chop-and-drop. Flanking are lavender, scented geranium (left), and borage. In most ecosystems that offer easy food for humans, the ground needs to be covered. Layers of leaves, organic matter from animals (poo, fur, carcasses, meal remains, etc.) , dropped branches and twigs, fallen flowers and fruit, and whatever else gravity holds close to the earth, compost to create soil and retain water and protect the soil from erosion and compaction. Areas that don’t have this compost layer are called deserts. If you want to grow an assortment of food for humans, you have to start building soil. Even in desert communities where there are some food plants growing, such as edible cactus, mesquite beans, etc., there is biodiversity on a more microscopic scale than in old growth forests. In deserts the soil needs to absorb what little rain there is and do it quickly before it evaporates, and plants have leaves adapted to have small leaf surfaces so as not to dry out, and there are few leaves to drop. Whereas in areas where there are large forests the weather is usually wetter, tall plants and thick underbrush provide multiple layers of protection both on the plants and when they fall to layer the earth.

Nasturtium reseeds itself annually, is edible with a bite of hotness, detracts aphids from other plants, and is charming. Don’t let it get away in natural areas, though. A quick way to build soil in plant guilds is to design for plants that will cover the ground. This isn’t necessarily the same groundcover as you would use to cover embankments. For instance, iceplant can be used in a pinch, but it really isn’t the best choice in most plant guilds unless you are in a very dry climate, and your plant guild is mostly desert-type plants: date palm, etc. Annuals can be squash or other aggressive food-producing vines such as unstaked tomatoes. However you don’t need to consider just ground-hugging plants; think sprawling shrubs.

Scented geraniums are a great ‘placeholder plant’. These Pelargoniums (not true geraniums) come in a wide variety of fragrances. We’ve found bird nests in these! When guests tour through Finch Frolic Garden, they often desire the lush foresty-feel of it for their own properties, but have no idea how to make it happen. This is where what I call ‘placeholder plants’ come in. Sprawling, low-cost shrubs can quickly cover a lot of ground, protect the soil, attract insects, often be edible or medicinal, be habitat for many animals, often can be pruned heavily to harvest green mulch (chop-and-drop), often can be pruned for cuttings that can be rooted for new plants to use or to sell, and are usually very attractive. When its time to plant something more useful in that area, the groundcover plant can be harvested, used for mulch, buried, or divided up. During the years that plant has been growing it has been building soil beneath it, protecting the ground from compaction from the rain. There is leave mulch, droppings from lizards, frogs, birds, rabbits, rodents and other creatures fertilizing the soil. The roots of the plant have been breaking through the dirt, releasing nutrients and developing microbial populations. Some plants sprawl 15′ or more; some are very low-water-use. All of this from one inexpensive plant.

Squash forms an annual groundcover around the base of this euphorbia. Depending upon your watering, there are many plants that fit the bill, and most of them are usable herbs. Scented geraniums (Pelargonium spp.), lavender, oregano, marjoram, culinary sage, prostrate rosemary, are several choices of many plants that will sprawl out from one central taproot. Here in Southern California, natives such as Cleveland sage, quail bush (which harvests salt from the soil), and ceanothus (California lilac, a nitrogen-fixer as well), are a few choices. Usually the less water use the plant needs, the slower the growth and the less often you can chop-and-drop it. With a little water, scented geraniums can cover 10 – 15 feet and you can use them for green mulch often, for rooted cuttings, for attracting insects, for medicine and flavoring, for cut greenery, for distillates if you make oils, etc.

Sweet potatoes make a great ground cover. Choose varieties that produce tubers directly under the plant rather than all along the stems so that you don’t have to dig up your whole guild to harvest. Groundcover plants shouldn’t be invasive. If you are planting in a small guild, planting something spreading like mint is going to be troublesome. If you are planting in larger guilds, then having something spreading in some areas, such as mint, is fine. However mint and other invasives don’t sprawl, but produce greenery above rootstock, so they are actually occupying more space than those plants that have a central taproot and can protect soil under their stems and branches. Here at Finch Frolic Garden, we have mint growing freely by the ponds, and in several pathways. Its job is to crowd out weeds, build soil, and provide aromatherapy. I’d much rather step on mint than on Bermuda grass, and besides being a superb tea herb, the tiny flowers feed the very small bees, wasps and flies that go unsung in gardens in favor of our non-native honeybees (there are no native honeybees in North America).

Here’s a general planting tip: position plants with fragrant leaves and flowers near your pathways for brush-by fragrance. You should have a dose of aromatherapy simply by walking your garden path. Mints are energizing, lavenders calming, so maybe plan your herbs with the pathways you take in the morning and evening to correspond to what boost you need at that time.

Consider groundcover plants and shrubs that will give you good soil and often so much more.

Next up: Vining Plants.

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

What makes up a plant guild. - Animals, Bees, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.

When set in motion the many parts of a plant guild will create a self-sustaining cycle of nutrition and water. By understanding the guild template and what plants fit where, we can plug in plants that fulfill those roles and also provide for us food, building materials, fuel and medicine as well as beauty.Plant the appropriate plants for where you are placing them, for your soil and water use, and stack them in a guild with compatible plants that you can use. The ground will be covered by a foliar density that will keep grasses and other weeds at bay and provide excellent habitat for a full range of animals and insects. By stacking plants in a guild you are bringing life and abundance back to your garden.

Does it still sound so complicated? Rather than try to learn the roles of all the plants in the world, start small. Make a list of all the plants you want to plant. List them under food bearing, culinary/medicinal herb, craft/building material, and ornamental. Then read up on those plants. What size are they at maturity? Do they need full sun, partial or full shade? If trees, do they have an upright growth so you may plant under them (stonefruit), or do they like to have their roots covered and don’t like plants directly under them (citrus and avocado)?

Citrus doesn’t like plants under its canopy, but does like plants outside its dripline. Are they annuals, perennials or biennials? What is their growth habit: sprawling, rooting where they spread, upright bushy, do they need support and can they cling or do they need to be tied to a support?

Will the plant twine on its own? Do they require digging up to harvest? Do they fix nitrogen in the soil? Do they drop leaves or are they evergreen? Are they fragrant? When are their bloom times? Fruiting times? Are they cold tolerant or do they need chill hours? How much water do they need? What are their companion plants (there are many guides for this online, or in books on companion planting.)

Do vines or canes need to be tied to supports? As you are acquainting yourself with your plants, you can add to their categorization, and shift them into the parts of a plant guild. Yes, many plants will be under more than one category… great! Fit them into the template under only one category, because diversity in the guild is very important.

Draw your guilds with their plants identified out on paper before you begin to purchase plants. Decide where the best location for each is on your property. Tropical plants that are thirsty and don’t have cold tolerance should go in well-draining areas towards the top or middle of your property where they can be easily watered. Plants that need or can tolerate a chill should go where the cold will settle.

Once it is on paper, then start planting. You don’t have to plant all the guilds at once… do it as you have time and money for it. Trees should come first. Bury wood to nutrify the soil in your beds, and don’t forget to sheet mulch.

Remember that in permaculture, a garden is 99% design and 1% labor. If you think buying the plants first and getting them in the ground without planning is going to save you time and money, think again. You are gambling, and will be disappointed.

Have fun with your plant guilds, and see how miraculous these combinations of plants work. When you go hiking, look at how undisturbed native plants grow and try to identify their components in nature’s plant guild. Guilds are really the only way to grow without chemicals, inexpensively and in a way that builds soil and habitat.

You can find the rest of the 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries .

- Animals, Bees, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds

Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries

California native sage and penstemon make great insectiaries. Insectiaries are plants which attract lost of pollinators to the rest of your plant guild. We’re not just talking honey bees. Actually, what Americans raise and call honey bees, any bees from the genus Apis which are colonial honey-producers, are all European. Of course there are also the African honey bees which are loose in America, but their ‘hotness’ – their radical and violent protective measures – are not welcome. There are no native honey bees in North America.

What we do have are hundreds of species of bees, wasps and flies which are native and which do most of the pollenization in non-poisoned gardens and fields. Here in Southern California where everything is smaller due to the low rainfall we have wasps, flies and bees which range in size from the inch-long carpenter bees to those the size of a freckle. A small freckle. In fact the best native pollinator we have is a type of hover fly that is about the size of a grain of rice.

Hoverflies (Family Syrphidae) are one of our best pollinators. My daughter Miranda hosts our Finch Frolic Garden Facebook page where she has posted albums of animals and insects found here, with identifications along with the photos so that you can tell what is the creature’s role in the garden (you don’t need to be a member of Facebook to view it).

“This photo is of a minute parasitoid wasp (likely Lysiphlebus testaceipes) which preys on aphids. The aphids here are Oleander Aphids (Aphis nerii), which infest our milkweed bushes.” Miranda Kennedy We notice and measure the loss of the honeybee, but no one pays attention to the hundreds of other ‘good guys’ that are native and do far more work than our imports. Many of our native plants have clusters of small flowers and that is to provide appropriate feeding sites for these tiny pollinators. Tiny bees need a small landing pad, a small drop of nectar that they can’t drown in, and a whole cluster of flowers close together because they can’t fly for miles between food sources.

Oregano doesn’t spread as much as other mints do, and can be kept in check by harvesting. Look closely at the blooms in summer and you’ll see lots of very tiny insects pollinating! If you’ve read my other Plant Guild posts, you’ve already familiar with this, but here it goes again. You’ve heard of the ‘Three Sisters’ method of planting by the Native Americans: corn, beans and squash. In Rocky Mountain settlements of Anasazi, a fourth sister is part of that very productive guild, the Rocky Mountain bee plant (Cleome serrulata). Its purpose was as an insectiary.

Borage is edible, medicinal, lovely and reseeds. So planting native plants that attract the insects native to your area is just as important as planting to attract and feed honey bees. Many herbs, especially within the mint and sage families, produce flowers that are enjoyed by most sizes of insects and are useful as food or medicine as well.

You’ll remember our old friend comfrey, which is also a mining plant and great green fertilizer! It also is a dining room for bumblebees. If you like flowers, here’s where you can possibly plant some of your favorites in your guild and not feel guilty about it! Of course, aesthetics is important and if you aren’t enjoying what is in your garden, you aren’t doing it right, so plant what makes you happy. As long as its legal.

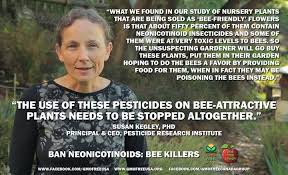

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.  Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.

Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.  Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

Talk about a sales twist! They don’t mention that it kills EVERYTHING else! When public demand is high enough, they will change their buying habits, and that will force change all the way down the line to the farmers. No matter how friendly and beautiful a nursery is and how great their plants look, insist that they prove they have insecticide-free plants from organic growers (even if they don’t spray plants themselves). Systemic insecticides are bee killers. And wasp and fly killers as well.

Of course many of the other guild members will also attract pollinators, and even be host plants for them as well. With a variety of insectiaries, you’ll receive the benefit of attracting many species of pollinator, having a bloom time that is spread throughout the year, and if a plant is chewed up by the insect it hosts (milkweed by Monarch caterpillars, for instance) there will be other blooms from which to choose.

Placing fragrant plants next to your pathways also gives you aromatherapy as you pass by.

And flowers are pretty. So plant them!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Soil, Water Saving

Plant Guild #7: Vines

Our varieties of squash several years ago. You may think that vines and groundcover plants are pretty interchangeable, and they can share a similar role. However, as we covered in the Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers these plants do not have to vine, but just cover large spaces close to the ground and coming from a single trunk or stem.

Sweet potatoes and yams make fantastic ground covers. The leaves are edible. Some root in one place, and some spread tubers over a larger area, so choose what is appropriate for digging up your harvest in your guild. They will die of frost. Vines can be large and heavy, small and delicate, perennial or annual. In a food plant guild vines are often food-bearing, such as squash. If you recall the legendary Three Sisters of planting – corn, beans and squash – there are two vines at work here. The corn forms a trellis for the light and grabby bean plant to climb upon (the bean fixing nitrogen in the soil as well as attracting pollinators with its flowers). The squash forms a low canopy all around the planted area. The big leaves keep moisture in, soften the raindrops to prevent erosion and deoxygenation, drop leaves to fertilize the soil, provide a large food crop, and attract larger pollinators. Even more than that, the squash protects the corn from raccoons. These masked thieves can destroy an entire backyard corn crop in a night, just when the corn is ripe. However, they don’t like walking where they can’t see the ground, so the dense squash groundcover helps keep them away.

Pipian from Tuxpan squash supported by a plum and a pepper tree. Vines are very important to use on vertical space, especially on trees. With global warming many areas now have extremely hot to scorching sun, and for longer periods. Intense sun will scorch bark on tender trees, especially young ones. By growing annual vines up the trees you are helping shade the trunk while producing a crop, and if the vines are legumes you are also adding nitrogen fertilizer.

Can you spot the squash in the lime tree? It is crescent shaped and pale. Be sure the weight of the mature vine isn’t more than the tree support can hold, or that the vine is so strong that it will wind its way around new growth and choke it. Peas, beans and sweetpeas are wonderful for small and weaker trees. When the vines die they can be added to the mulch around the base of the tree, and the tree will receive winter sunlight. When we plant trees, we pop a bunch of vining pea (cool weather) or bean (warm weather) seeds right around the trunk. Larger, thicker trees can support tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, and squash of various sizes, as well as gourds. Think about how to pick what is up there! We allowed a alcayota squash to grow up a sycamore to see what would happen, and there was a fifteen pound squash hanging twelve feet above the pathway until it came down in a heavy wind!

These zuchinno rampicante, an heirloom squash that can be eaten green or as a winter squash, form interesting shapes as they grow. These ‘swans’ and Marina are having a stare-off. Nature uses vertical spaces for vines in mutually beneficial circumstances all the time, except for notable strangler vines. For instance in Southern California we have a wild grape known as Roger’s Red which grows in the understory of California Live Oaks. A few years ago there appeared in our local paper articles declaiming the vines, saying that everyone should cut them down because they were growing up and over the canopy of the oaks and killing them. The real problem was that the oaks were ill due to water issues, or beetle, or compaction, and had been losing leaves. The grape headed for the sun, of course, and spread around the top of the trees. The overgrowth of the grape wasn’t the cause of the problem, but a symptom of a greater illness with the oaks.

Zucchini! Some vines are not only perennial, but very long-lived and should be placed where they’ll be happiest and do the most good. Kiwi vines broaden their trunks over time and with support under their fruiting stems can be wonderful living shade structures. A restaurant in Corvallis, Oregon has one such beauty on their back patio. There is something wonderful about sitting in the protection of a living thing.

Wisteria chinensis is a nitrogen-fixer with edible flowers (and poisonous other parts), has stunning spring flowers and can make a nice deciduous vine to cover a canopy. It does spread vigorously, but can be trained into a standard, and are fairly drought tolerant when mature. Passionvines can grow up large trees where they can receive a lot of light. Their fruit will drop to the ground when ripe. The vines aren’t deciduous, so the tree would be one where the vine coverage won’t hurt the trunk.

Dragonfruit aren’t exactly a vine, but they can be trained up a sturdy tree. Vines such as hops will reroot and spread wherever they want, so consider this trait if you plant them. Because the hops need hand harvesting and the vines grow very long, it is probably best to put them on a structure such as a fence so you can easily harvest them.

So consider vines as another important tool in your toolbox of plants that help make a community of plants succeed.

Next in the Plant Guild series, the last component, Insectiaries. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Compost, Gardening adventures, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Natives, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants

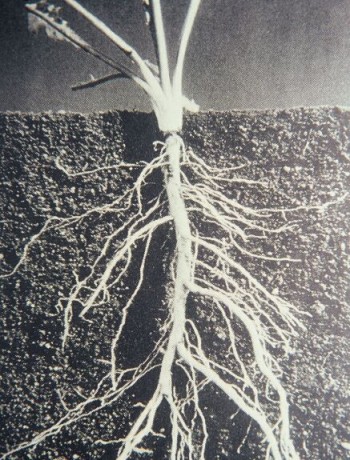

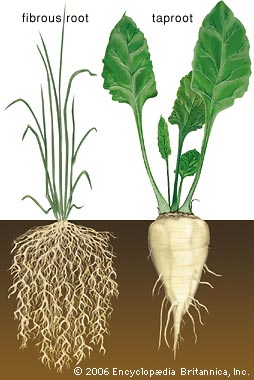

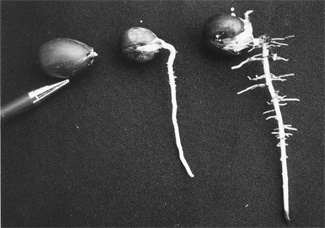

The beauteous taproot. In the last post we explored one way plants take nitrogen out of the air and fix it in the soil. Now we’ll explore how plants take nutrients from deep in the soil and deliver them to the soil surface. This is another way that plants create high nutrient topsoil.

All rooted plants gather nutrition from the soil, store it in their leaves, flowers and fruit, and then create topsoil as these products fall to the ground. Every plant is a vitamin pill for the soil. When you pull ‘weeds’, clear your garden, prune and otherwise amass greenery and deadwood, you are gathering vitamins and minerals for your soil. Bury it. All of it. If its too big to bury, then chip it and use it as top mulch. Allow that nutrition to return to the soil from whence it came. No stick or leaf should leave your property! Period.

Fiberous roots hold soils together, and taproots dig. There are mainly two kinds of root systems: fibrous (like many grasses) and taprooted. Some taprooted plants grow very deeply. Those plants that are deemed ‘mining’ plants go the extra mile. I envision mining plants as the gruff gentlemen of the plant guild: tough and weathered, dressed in pith helmet and explorer clothes with a larger-than life character and a heart of gold.

A monument to Sir Henry Morton Stanley. I don’t know if he had a heart of gold or was gruff. Okay, too many old movies on my part. The roots of mining plants are large taproots that explore the depth of the soil searching for deep water. Depending upon the size of the plant, these roots can break through hardpan and heavy soils. They create oxygen and nutrient channels, digging tunnels that weaker roots from less bold plants and soft-bodied soil creatures can follow. When these large roots die they decompose deep in the ground, bringing that all-important organic material into the soil to feed microbes. Meanwhile these Indiana Jones’s of the root world are finding pockets of minerals deep in the soil – far below the topsoil and where other roots can’t reach – and are taking them into their bodies and up into their leaves. When these leaves die off and fall to the ground they are a super rich addition to the topsoil. Often the deep taprooted plants have a sharp scent or taste. Many weeds found in heavy soils are mining plants, sent by Mother Nature to break up the dirt and create topsoil. Dicotyledonous (dicot) plants have deep taproots, if you are into that kind of thing. The benefits of a plant having a deep taproot is not only to search for deep water, but to store a lot more sugar in the root, be anchored firmly, and to withstand drought better.

So who are these helpful gentlemen adventurers of the plant guilds? Comfrey and artichoke are two commonly used mining plants. Also members of the, radish, mustard, and carrot family such as, parsnip, root celery, horseradish, burdock, parsley, dandelion, turnip, and poppy to name a few. There is also milkweed (Asclepias), coneflower, chicory, licorice, pigeon pea, and for California natives there is sagebrush, Matilija poppy, oaks, mesquite, Palo Verde and many more. Most deep taprooted plants don’t transplant well because their straight taproot is often much longer than the top of the plant. Check out a sprouted acorn. The taproot is many times as deep as the top is high.

Three day’s difference in germinating acorns. Talk about taproot! Image from www.landscapeonline.com. Yet some mining plants such as comfrey and horseradish can be divided or will sprout from pieces of the root left in the ground. Deep taprooted weeds seem to all be like that, at least on my property!

Horseradish: the root is edible and medicinal, and the leaves are a spicy treat!

Grating horseradish for sauce, and still tearing up! Now for a little comfrey prosthelytizing: Comfrey keeps coming back when chopped, so it is often grown around fruit producing trees to be chopped and dropped as a main fertilizer. Its leaves are so high in nutrition that they are a compost activator, an excellent hen and livestock food (dried it has 26% protein), and have been heavily used in traditional medicine. Also called Knitbone, the roots contain allantoin, a substance also found in mother’s milk, which among other benefits helps heal bone breaks when applied topically.

A handsome comfrey plant working in the garden. The plant also has flowers that bees and other insects love. It spreads by seeds as well as divisions, and non-permaculture gardeners don’t like it escaping in their gardens. I only wish that mine would spread faster, to create more fertilizer. Comfrey grows the best greens with some irrigation and better soil, so it is perfect for use around fruit trees.

So when planting a guild you can easily plant miners that are edible. If you harvest those deep taproots, such as carrots or parsnips, then be sure to trim the greens and let them fall on the spot, so the plant will have done its full duty to the soil. Unless the plant can take division, such as the aforementioned comfrey, then planting seeds are best. Deep taprooted plants in pots are often stunted and either don’t survive transplanting well, or will take a long time to grow on top because they need to grow so much on the bottom first.

Next up: the exciting groundcover plants!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #6: Groundcover Plants, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-fixing Plants

Photo credit USU What is the first of the three chemicals in bagged NPK fertilizer? Nitrogen. Nitrogen is so important for the health of plants that isolated into a chemical, along with phosphorus and potassium, it can keep plants alive and active. But as the human body becomes ill when it is just fed junk food each and every day, so will your plants when they can’t assimilate the other nutrients in the soil.

Again, in permaculture it is all about the microorganisms in the soil. We provide food, water and shelter for them, and they open up the nutrients that are already in the soil on which the plants feed. When you dump a lot of anything on the soil, its going to kill microbes. Dumping bagged NPK fertilizer on the soil burns the creatures in the soil, just as if you poured acid on them. They die, and it will be awhile before the irrigation and rains delutes those chunks of fertilizer enough so that microbes can again live in the soil surface, but by then its time to dump more chemicals on the ground. The plant gets a high, but will never be able to adequately draw out the trace minerals it really needs to complete its diet, which soil microbes provide to it, because they are burned out of existence by the chemicals.

It would be pompous for us the believe that plants, which began about 450 million years ago on Earth, just fiddled around until their true keepers (humans) came along and evolved enough to produce chemical nitrogen to dump onto their roots.

photo credit www.bio.miami.edu In fact, there are many ways that nature gets nitrogen into the soil. Lightning strikes, rainfall, cut greens, fresh poop, fallen ripe fruit, all help. Most of all, there are soil bacteria which can transform atmospheric nitrogen into fixed nitrogen: inorganic compounds that are usable by plants. More than 90% of nitrogen harvesting is done by these organisms. There are non-symbiotic (free-living) bacteria called cyanobacteria (or blue-green algae), and there are symbiotic bacteria that form relationships with particular plants. These symbiotic bacteria, namely rhizobium and Frankia, invade the root hairs of select plants and create enlargements on the roots called nitrogen nodules. This process sounds and looks similar to wasps stinging oak branches and creating galls; however, the frankia are helping the plant; symbiotic rather than parasitical. Atmospheric nitrogen is inert, therefore unusable by the plant. When the bacteria get their little hands into it, by changing it into ammonia and nitrogen dioxide the nitrogen is freed up to be used as the plant and the bacteria needs. When the plant roots die, the nitrogen is released into the soil. So, the plant, with the help of the bacteria, is sucking nitrogen out of the air, breaking it down and releasing it as a usable nutrient source in the soil. Who needs chemical fertilizer?

Nitrogen-fixing Bacteria, Sem Photograph Only certain plants still have the capability to join in this symbiotic relationships; some families have just a few species that can do it, and it is unknown if they developed the talent, or if the rest of the family eventually lost the talent. Legumes and all members of the Fabaceae family is the most commonly known and used nitrogen fixing family. Peas, beans, cowpeas, and clover are all commonly used cover crops. When mowed they produce both green mulch and release nitrogen into the soil. However, there are many shrubs and trees that are also nitrogen fixers. California Redbud tree, mesquite, mountain mahoganies, alders, ceanothus (California lilac), sea buckthorn, bayberries, cassia, acacias, lupines, and many more. There are also riparian plants such as azola, gunnera, some lichen and cycads which fix nitrogen with cyanobacteria.

California redbud trees offer beautiful spring flowers which are edible, lovely fall color, and are nitrogen-fixers as well! In fact, 40-60% of native plants are nitrogen fixers. When you are planning your garden, your vegetable beds, your native Zone 5, and especially your orchards, you should be incorporating that percentage of nitrogen fixers into your design. Many of these can be mowed as cover crops, or used as quick-growing nursery plants, as canopy, or as chop-and-drop.

Chop-and-drop is when you grow your own fertilizer around your crop plants, and instead of purchasing and distributing fertilizer, a couple of times a year you take out a hand scythe and quickly cut back the nitrogen-fixing plants, scattering the tops around your food plants as mulch. When the top of the nitrogen-fixing plant is severely cut, the plant doesn’t need as much root base so it allows some to die, which distributes nitrogen into the soil. A double-whammy for your soil, and a small, easy and satisfying workout for you. Shazam.

Very important: when planting nitrogen-fixing plants there has to be the compatible bacterium in your soil for the whole thing to work. Purchasing inoculated seed for the first sowing on new planting areas is very important. As different bacteria react with different plants, study up some to make sure you are buying the right stuff if you are going to inoculate seed yourself. Then make sure that you are providing those tender bacteria with food, water and shelter – habitat – so that they can live and prosper. And what is the best habitat for soil microbes around food producing plants? Yep, mulch. Sheet mulch especially, and several inches of chopped leaves best of all.

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving

Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy!

The many layers of a food forest, Finch Frolic Garden. Yours doesn’t have to be this rampant and wild; your plant guilds can look perfectly proportioned and decorative and still be permaculture. The next part of this scintillating series of What Is A Plant Guild focuses on sub-canopy, or the understory. Sub-canopy does many of the same things that upper canopy does, in a more intensive way.

Smaller trees are ‘nurseried’ in with the help of faster-growing canopy trees; in other words, the upper canopy helps shade and protect the sub-canopy from scorching sun, high winds, pounding hard rain and hail, etc. However, sub-canopy trees can also be made of the slower, longer-lived canopy trees that will eventually dominate the plant guild/forest. You can try these guys for tree falling. I’ve talked about how, if an area of forest was wiped clear and roped off, in a hundred years the beginnings of a hardwood forest will have begun. This is due to succession plants making the soil ready for the next. Each plant has a purpose. This phrase is an essential mantra in permaculture because it lets you understand what the plants are doing and then you can let them do it. So if you planted a fast-growing soft wood canopy tree, maybe even one that is a nitrogen-fixer, such as ice cream bean, or acacia, with a sub-canopy trees that include both something that is going to stay relatively small such as a semi-dwarf fruit tree, along with a slower growing, hardwood tree such as an oak which will eventually become the true canopy tree years down the line, then the original softwood tree would eventually be sacrificed and used as mulch and hugelkultur after the hardwood tree had gained enough height. Wow, that was a long sentence. At first that hardwood tree would be part of the sub-canopy until it grows up. Meanwhile there are other true sub-canopy trees that stay in that height zone for their life.

What makes up a plant guild. Remember, too, that plant guilds are relative in size. If you have a small backyard you may not have room for a tall canopy tree, especially if it is detrimental to the rest of the property. So scale the whole guild down. Canopy for you could be a dwarf fruit tree, and sub-canopy could be blueberry bushes. In a vegetable setting the canopy could be corn or Jerusalem artichokes, where you either leave the dead canes up overwinter (a great idea to help the birds), or chop and drop them to protect the soil, which mimics the heavy leaf drop from a deciduous tree. The plant guild template is the same; the dimensions change with your needs and circumstance. Get more details on how to take good care of the trees with the help of experts.

So sub-canopy buffers sunlight coming in from an angle.

It receives rain from the upper canopy further slowing it down and shattering the droplets so that it doesn’t pound the earth. The lower branches also help catch more fog, allowing it to precipitate and drip down as irrigation. Leaves act as drip irrigation, gathering ambient moisture, condensing it, helping clean it, and dripping it down around the ‘drip line’ of the trees, just where the tree needs it.

An oak working a temp job as sub-canopy until it grows into canopy, being a support for climbing roses and nitrogen-fixing wisteria. This is the formal entrance to Finch Frolic Garden. With its sheltering canopy it holds humidity closer to the ground. In the previous post I talked about the importance of humidity in dry climates for keeping pollen hydrated and viable.

It further helps calm and cool winds, and buffers frost and snow damage. Sub-canopy gives a wide variety of animals the conditions for habitat: food, water, shelter and a place to breed. While the larger birds, mostly raptors, occupy the upper canopy, the mid-sized birds occupy the sub-canopy. Depending upon where you live, a whole host of other animals live here too: monkeys, big snakes, leopards, a whole host of butterflies and other insects using the leaves as food and to form chrysalis, tree squirrels, etc. Although many of these also can use canopy, it is the sub-canopy that provides better shelter, better materials for nesting, and most of the food supply. And again, the more animals, the more organic materials (poop, fur, feathers, dinner remains) will fall to fertilize the soil.

Sub-canopy gives us humans a lot of food as well, for in a backyard plant guild this can be the smaller fruit trees and bushes.

Sub-canopy also provides more vertical space for vines to grow. More vines mean more food supply that is off the ground. A famous example of companion planting is the ‘three sisters’ Native American method… what tribe and where I’m not sure of… where corn is planted with climbing beans and vining squash. The corn, as mentioned before, is the canopy, the beans use the corn as vertical space while also fixing nitrogen in the soil (we’ll discuss nitrogen fixers in another post), and the squash is a groundcover (also will be covered in another post). There is more to the three sisters than you think. Raccoons can take down a corn crop in a night; however, they don’t like to walk where they can’t see the ground, i.e. heavy vines, so the squash acts as a raccoon deterrent. To stray even further off-topic, there is also a fourth sister which isn’t talked about much, and that is a plant that will attract insects.

Back to sub-canopy, while some of it can be long term food production trees or plants, it too can also have shorter chop-and-drop trees. Chop-and-drop is a rather violent term given to the process of growing your own fertilizer. Most of these trees and plants are also nitrogen fixers. These fast-growing plants are regularly cut, and here is where the difference between pruning and chopping comes to bear, because you aren’t shaping and coddling these trees with pruning, you are quickly harvesting their soft branches and leaves to drop on the ground around your plant guild as mulch and long term fertilizer. If these trees are also nitrogen fixers, then when you severely prune them the nitrogen nodules on the roots will be released in the soil as those roots die; the tree will adjust the extent of its roots to the size of its canopy because with less canopy it cannot provide enough nutrients for that many roots, and it doesn’t need that many roots to provide food for a smaller canopy. Wow, another huge sentence. In this system you are growing your own fertilizer, which is quickly harvested maybe only a couple of times a year. Chemical-free. So, by planting sub-canopy that is long term food producing trees such as apricots or apples, along with smaller trees and shrubs that are also sub-canopy but are sacrificial to be used as fertilizer such as senna or acacia or whatever grows well in your region, you have the most active and productive part of your plant guild.

Sub-canopy, therefore, provides shelter for hardwoods, provides a lot of food for humans as well as habitat for so many animals, it provides fertilizer both because of its natural leaf drop and because of those same animals living in it, but also as materials for chopping and dropping, it buffers sun, wind and rain, holds humidity, offers vertical space for food producing vines which will then be in reach for easier harvesting, and much more that I haven’t even observed yet but maybe you already have.

The next part of the series will focus on nitrogen-fixers! Stay tuned. You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

Plant Guilds #2: Upper Canopy

An oak is home to over 300 species. Not counting human. Whether you are planting small plants in pots, ornamentals in your yard or a food forest, you need plants that will provide an upper canopy for others. If you have small plants, then you will have a short canopy. Maybe your canopy is a tomato plant. Maybe its an oak. Whatever it is, canopy has many functions.

Upper canopy provides shade so that other plants can grow. It drops leaves, bark, flowers and seeds and/or fruit to provide compost and food for all levels of animals down to soil microbes. Canopy provides protective shelter for many kinds of mammals, birds, reptiles and insects as they hide under the leaves. A mature oak is home to over 300 species. Old scarred canopy full of holes is the natural home for honeybees, and many types of bird and other animal. It is a storage unit for acorns gathered by woodpeckers. Where you have animals, you have droppings. All the poo, feathers, regurgitated pellets, fur, scales and other organic waste that falls from canopy is vitally important for the health of the soil below.

Canopy provides a perch for raptors and larger birds that help with rodent control.

Canopy helps slow the wind; the fewer trees we have the harder the winds. Canopy also filters the wind, blocking dust and other debris. Canopy helps cool and moisturize the wind. The leaves of canopy trees help buffer the rain. Rain on bare ground is as compacting as driving over the dirt with a tractor. If rain hits leaves it bounces, rolls or shatters. Rain can then hit other layers below the canopy, finally rolling through leaf mulch to percolate into the soil without compacting it.

Canopy catches moisture as well. Here in Southern California we may not receive a lot of rain, but we do have moisture during the night.

Often I’ve walked through Finch Frolic Garden of a morning to feed the hens, and the garden sounded as if it had its own special rain cloud over it. That is because moisture condenses on the leaves and rolls off. The more canopy and the higher the canopy, the more water we can collect. In that same way, canopy begins to hold humidity on the property, which the rest of the guild contributes to. Pollen dries out. With longer, hotter, drier summers there is worse pollination even if the pollinators are active, because the pollen isn’t viable. Less humidity equals fewer fruits, nuts and vegetables. Therefore, the more canopy, and other parts of a guild, the moister the air and the better the harvest.

Often I’ve walked through Finch Frolic Garden of a morning to feed the hens, and the garden sounded as if it had its own special rain cloud over it. That is because moisture condenses on the leaves and rolls off. The more canopy and the higher the canopy, the more water we can collect. In that same way, canopy begins to hold humidity on the property, which the rest of the guild contributes to. Pollen dries out. With longer, hotter, drier summers there is worse pollination even if the pollinators are active, because the pollen isn’t viable. Less humidity equals fewer fruits, nuts and vegetables. Therefore, the more canopy, and other parts of a guild, the moister the air and the better the harvest.

Canopy is in connection with all other plants in its community, linked via webs called mycorrhizal fungi. Through these webs the canopy sends chemical messages and nutrients to other plants. Every plant in the community benefits from the strong communications from the canopy trees.

Canopy builds soil. Canopy trees are large on top and equally large underground. Tree root growth can mirror the height and width of the above-ground part, and it can be larger. Therefore canopy trees and plants break through hard soil with their roots, opening oxygen, nutrient and moisture pathways that allow the roots of other plants passage, as well as for worms and other decomposers. As the roots die they become organic material deep in the soil – effortless hugelkultur; canopy is composting above and below the ground. Plants produce exudates through their roots – sugars, proteins and carbohydrates that attract and feed microbes. Plants change their exudates to attract and repel specific microbes, which make available different nutrients for the plant to take up. A soil sample taken in the same spot within a month’s time may be different due to the plant manipulating the microbes with exudates. Not only are these sticky substances organic materials that improve the soil, but they also help to bind loose soil together, repairing sandy soils or those of decomposed granite. The taller the canopy, the deeper and more extensive are the roots working to build break open or pull together dirt, add nutrients, feed and manage microbes, open oxygen and water channels, provide access for worms and other creatures that love to live near roots.

Canopy roots have different needs and therefore behave differently depending upon the species. Riparian plants search for water. If you have a standing water issue on your property, plant thirsty plants such as willow, fig, sycamore, elderberry or cottonwood. In nature, riparian trees help hold the rain in place, storing it in their massive trunks, blocking the current to slow flooding and erosion, spreading the water out across fields to slowly percolate into the ground, and turning the water into humidity through transpiration. The roots of thirsty plants are often invasive, so be sure they aren’t near structures, water lines, wells, septic systems or hardscape. Some canopy trees can’t survive with a lot of water, so the roots of those species won’t be destructive; they will flourish in dry and/or well-draining areas building soil and allowing water to collect underground.

In large agricultural tracts such as the Midwest and California’s Central Valley, the land is dropping dramatically as the aquifers are pumped dry. Right now in California the drop is about 2 inches a month. If the soil is sandy, it will again be able to hold rainwater, but without organic materials in the soil to keep it there the water will quickly flow away. If the soil is clay, those spaces that collapse are gone and no longer will act as aquifers… unless canopy trees are grown and allowed to age. Their root systems will again open up the ground and allow the soil to be receptive to water storage. Again, roots produce exudates, and roots swell up and die underground leaving wonderful food for beneficial fungi, microbes, worms and all those soil builders. The solution is the same for both clay and sandy soils – any soil, for that matter. Organic material needs to be established deep underground, and how best to do that than by growing trees?

In permaculture design, the largest canopy is often found in Zone 5, which is the native strip. In Zone 5 you can study what canopy provides, and use that information in the design of your garden.

How do you achieve canopy in your garden? If your canopy is something that grows slowly, then you will need to nursery it in with a fast-growing, shorter-lived tree that can be cut and used as mulch when the desired canopy tree becomes well established. Some trees need to be sacrificial to insure the success of your target trees. For instance, we have a flame tree that was part of the original plantings of the garden. It is being shaded out by other trees and plants, and all things considered it doesn’t do enough for the garden to be occupying that space (everything in your garden should have at least three purposes). However a loquat seeded itself behind the flame tree, and the flame tree helped nursery it in. We love loquats, so the flame tree may come down and become buried mulch (hugelkultur), allowing that sunlight and nutrient load to become available for the loquat which is showing signs of stress due to lack of light. With our hotter, drier, longer summers, many fruit trees need canopy and nurse trees to help filter that intense heat and scorching sunlight. Plan your garden with canopy as the mainstay of your guild.

How do you achieve canopy in your garden? If your canopy is something that grows slowly, then you will need to nursery it in with a fast-growing, shorter-lived tree that can be cut and used as mulch when the desired canopy tree becomes well established. Some trees need to be sacrificial to insure the success of your target trees. For instance, we have a flame tree that was part of the original plantings of the garden. It is being shaded out by other trees and plants, and all things considered it doesn’t do enough for the garden to be occupying that space (everything in your garden should have at least three purposes). However a loquat seeded itself behind the flame tree, and the flame tree helped nursery it in. We love loquats, so the flame tree may come down and become buried mulch (hugelkultur), allowing that sunlight and nutrient load to become available for the loquat which is showing signs of stress due to lack of light. With our hotter, drier, longer summers, many fruit trees need canopy and nurse trees to help filter that intense heat and scorching sunlight. Plan your garden with canopy as the mainstay of your guild.Therefore a canopy plant isn’t in stasis. It is working above and below ground constantly repairing and improving. By planting canopy – especially canopy that is native to your area – you are installing a worker that is improving the earth, the air, the water, the diversity of wildlife and the success of your harvest.

What makes up a plant guild. Canopy is improving the water storage of the soil and increasing potential for aquifers. The more site-appropriate, native canopy we can provide in Zone 5, and the more useful a canopy tree as the center of a food guild, the better off everything is. All canopy asks for in payment is mulch to get it started.

Next week we’ll explore sub-canopy! Stay tuned! You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

-

Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series.

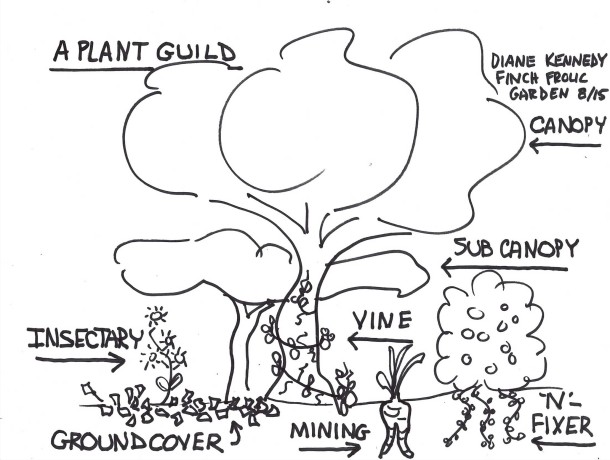

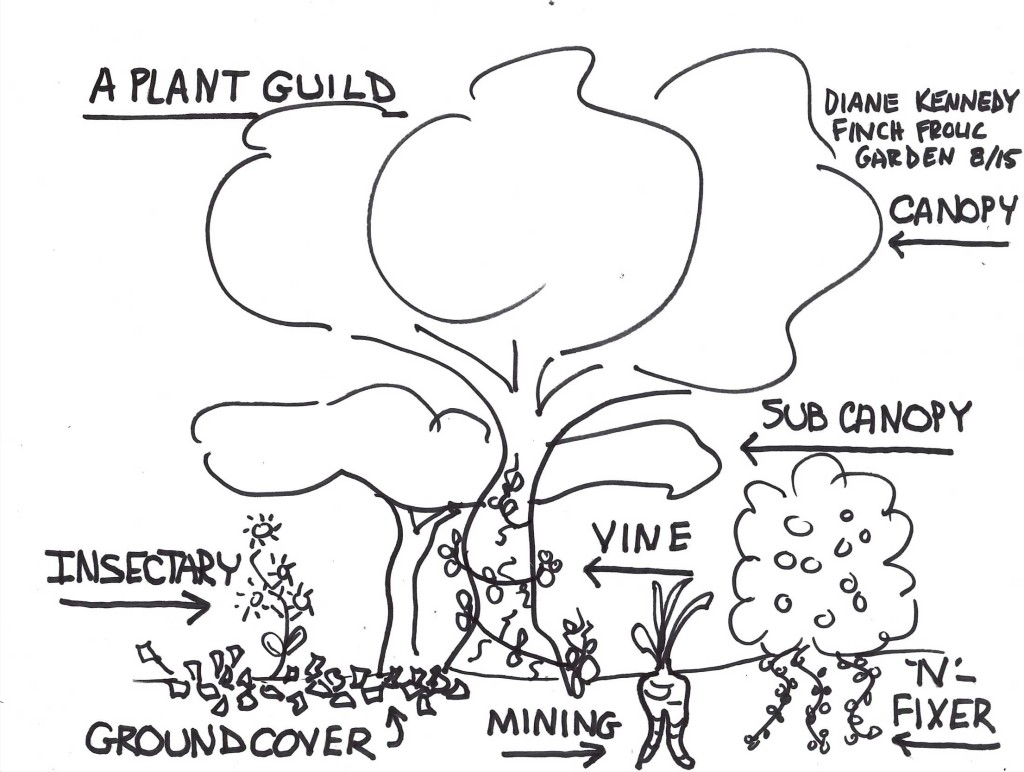

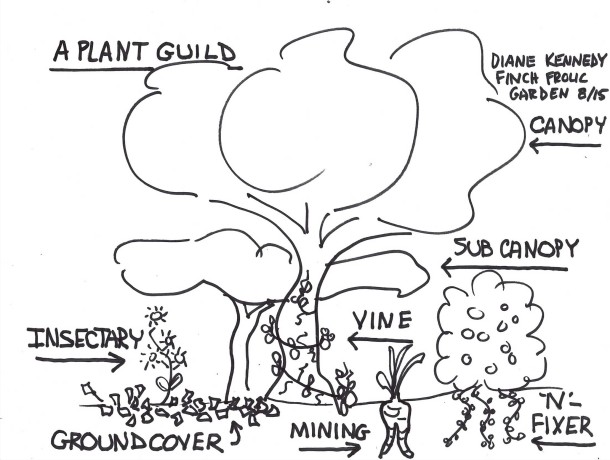

This is an appropriate definition of a guild: an association of people for mutual aid or the pursuit of a common goal. In permaculture a guild is a collection of plants that help each other grow and don’t compete for all the same nutrients.

This is an appropriate definition of a guild: an association of people for mutual aid or the pursuit of a common goal. In permaculture a guild is a collection of plants that help each other grow and don’t compete for all the same nutrients.

What makes up a plant guild. Guild design is based upon natural plant communities in healthy living situations. As in a healthy human community, each component has its own purpose and contributes to the health of the whole without diminishing itself. Unfortunately, I know more successful plant guilds than human communities; taking permaculture lessons into the neighborhood and politics is a whole other facet of permaculture that I’m not tackling in this series.

If you scraped an acre of forest down to dirt, removed all the plant materials, then fenced that area off, after a hundred years had passed, through succession, nature would have created the beginnings of an old growth forest. Nature does this by healing the ground with specific plants, one type of plant healing the ground so that the next larger plant can grow. You have weeds, scrub, bushes, low canopy, soft wood upper canopy, and eventually hardwood canopy. Every plant has a purpose, and we’ll discuss those purposes in this series, and how you use them in a guild.

For instance, California poppies grow well in disturbed soil. They are one of the plants nature has used to fix soil dug up by wild animals or shifting land mass. Their roots and the nutrients the dead plants bring to the soil surface help settle and heal the earth for the next succession. Once the soil has settled, poppies don’t grow well in that place anymore, but other plants will. California park officials have to till poppy fields to insure an annual bloom and the visitors -and funding – the fields attract. The forward progression of plant succession in these fields has been stopped.

California lilac blooming throughout the elfin forest. In the Southern California hills and mountains there are small forests of tall shrubs called California lilac, or ceanothus. Ceanothus is a nitrogen fixer (I’ll go into what that is in another post), so it is building soil as it grows and dies. I met a man who is receiving government funds to ‘reforest’ a portion of local mountains, and he’s bulldozing acres of ceanothus and planting pine trees in their stead. The soil isn’t ready for pine trees, which is the soft wood stage of succession. As we are going into decades long drought, and there is great tree loss due to a pine beetle, his project is doing much more harm than good. In fact, he has such a small success rate that I wonder why he’s still pursuing the project.

When looking at a property, plants can give you clues as to the weather, moisture and soil type. Do you have lots of wild radish and other deep tap-rooted plants? You probably have heavy soil that needs breaking up. Are there lots of low grasses? You probably have sandy soil that needs gluing together. Is there native sumac? Then frost doesn’t linger at that spot. If you learn the growing requirements of native plants and common invasive weeds, you can understand your property by what is successfully growing on it already. Are there any green patches? Either you’ve found the septic leach lines, or an irrigation leak, or a natural water settlement area. Are there clusters of willows, sycamore, elderberry, or Coastal live oaks? There is water close by.

In any mature natural area that hasn’t fallen victim to intentional grazing you’ll find plants of many species growing together. The plant guilds have these components: canopy, sub-canopy, nitrogen-fixer, groundcover, mining plant, vine and insectiary. In the following series I’ll describe in depth each of these components, why they are important and how they work in the guild. When you understand the template then planting in guilds becomes natural, fun, and best of all successful. Stay tuned! You can find the rest of the 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Compost, Fruit, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Herbs, Hugelkultur, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Ponds, Predators, Rain Catching, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Vegetables, Water Saving, Worms

The Mulberry Guild

The renovated and planted mulberry guild. One of our larger guilds has a Pakistani mulberry tree that I’d planted last spring, and around it had grown tomatoes, melons, eggplant, herbs, Swiss chard, artichokes and garlic chives.

Mulberry guild with last year’s plant matter and unreachable beds. This guild was too large; any vegetable bed should be able to be reached from a pathway without having to step into the bed. Stepping on your garden soil crushes fungus and microbes, and compacts (deoxygenates) the soil. So of course when I told my daughter last week that we had to plant that guild that day, what I ended up meaning was, we were going to do a lot of digging in the heat and maybe plant the next day. Most of my projects are like this.

Lavender, valerian, lemon balm, horehound, comfrey and clumping garlic chives were still thriving in the bed. Marsh fleabane, a native, had seeded itself all around the bed and had not only protected veggies from last summer’s extreme heat, but provided trellises for the current tomatoes.

Fleabane stalks from last year, with new growth coming from the roots. Marsh fleabane is an incredible lure for hundreds of our tiny native pollinators and other beneficial insects. Lots of lacewing eggs were on it, too. The plants were coming up from the base, so we cut and dropped these dead plants to mulch the guild.

The stalks of fleabane are hollow… perfect homes for small bees! The stems were hollow and just the right size to house beneficial bees such as mason bees. This plant is certainly a boon for our first line of defense, our native insects.

We also chopped and dropped the tomato vines. Tomatoes like growing in the same place every year. With excellent soil biology – something we are still working on achieving with compost and compost teas – you don’t have to rotate any crops.

Slashed and dropped tomato and fleabane. We had also discovered in the last flood that extra water through this heavy clay area would flow down the pathway to the pond, often channeled there via gopher tunnels.

The pathway is a water channel during heavy rains. It needs fixing. We decided to harvest that water and add water harvesting pathways to the garden at the same time. We dug a swale across the pathway, perpendicular to the flow of water, and continued the swale into the garden to a small hugel bed.

Swale dug on contour through the pathway and across the guild. Hugelkultur means soil on wood, and is an excellent way to store water in the ground, add nutrients, be rid of extra woody material and sequester carbon in the soil. We wanted the bottom of the swale to be level so that water caught on the pathway would slowly travel into the bed and passively be absorbed into the surrounding soil. We used our wonderful bunyip (water level).

Using a bunyip to make the bottom of the swale level. Water running into the path will now be channeled through the guild. Because of the heavy clay involved we decided to fill the swale with woody material, making it a long hugel bed. Water will enter the swale in the pathway, and will still channel water but will also percolate down to prevent overflow. We needed to capture a lot of water, but didn’t want a deep swale across our pathway. By making it a hugel bed with a slight concave surface it will capture water and percolate down quickly, running along the even bottom of the swale into the garden bed, without there being a trippable hole for visitors to have to navigate. So we filled the swale with stuff. Large wood is best for hugels because they hold more water and take more time to decompose, but we have little of that here. We had some very old firewood that had been sitting on soil. The life underneath wood is wonderful; isn’t this proof of how compost works?

The activity under an old log shows so many visible decomposers, and there are thousands that we don’t see. We laid the wood into the trench.

Placing old logs in the swale. If you don’t have old logs, what do you use? Everything else!

This giant palm has been a home to raccoons and orioles, and a perch for countless other birds. The last big wind storm distributed the fronds everywhere. We are wealthy in palm fronds.

Three quick cuts (to fit the bed) made these thorny fronds perfect hugelbed components. We layered all sorts of cuttings with the clay soil, and watered it in, making sure the water flowed across the level swale.

We filled the swale with fronds, rose and sage trimmings, some old firewood and sticks, and clay. As we worked, we felt as if we were being watched.

Can you spot the duck in this photo? Mr. and Mrs. Mallard were out for a graze, boldly checking out our progress. He is guarding her as she hikes around the property, leading him on a merry chase every afternoon. You can see Mr. Mallard to the left of the little bridge.

This male mallard and his mate, who is ‘ducked’ down in front of him, enjoyed grazing on weeds and watching we silly humans work so hard. After filling the swale, we covered the new trail that now transects the guild with cardboard to repress weeds.

Cardboard laid over the hugelswale. Then we covered that with wood chips and delineated the pathway with sticks; visitors never seem to see the pathways and are always stepping into the guilds. Grrr!

The cardboard was covered with wood chips and the pathway delineated with sticks. Where the trail curves to the left is a small raised hugelbed to help hold back water. At this point the day – and we – were done, but a couple of days later we planted. Polyculture is the best answer to pest problems and more nutritional food. We chose different mixes of seeds for each of the quadrants, based on situation, neighbor plants, companion planting and shade. We kept in mind the ‘recipe’ for plant guilds, choosing a nitrogen-fixer, a deep tap-rooted plant, a shade plant, an insect attractor, and a trellis plant. So, for one quarter we mixed together seeds of carrot, radish, corn, a bush squash, leaf parsley and a wildflower. Another had eggplant, a short-vined melon (we’ll be building trellises for most of our larger vining plants), basil, Swiss chard, garlic, poppies, and fava beans. In the raised hugelbed I planted peas, carrots, and flower seeds.

In the back quadrant next to the mulberry I wanted to trellis tomatoes.

This quadrant by the mulberry needed a trellis for tomatoes. I’d coppiced some young volunteer oaks, using the trunks for mushroom inoculation, and kept the tops because they branched out and I thought maybe they’d come in handy. Sure enough, we decided to try one for a tomato trellis. Tomatoes love to vine up other plants. Some of ours made it about ten feet in the air, which made them hard to pick but gave us a lesson in vines and were amusing to regard. So we dug a hole and stuck in one of these cuttings, then hammered in stakes on either side and tied the whole thing up.

Tying the trunk to two stakes with twine taken from straw bales. Love the blue color! The result looks like a dead tree. However, the leaves will drop, providing good mulch, the tiny current tomatoes which we seeded around the trunk will enjoy the support of all the small twigs and branches, and will cascade down from the arched side.

The ‘dead tree’ look won’t last long as the tomatoes climb over it and dangle close to the path for easy harvesting. We seeded the area with another kind of carrots (carrots love tomatoes!) and basil, and planted Tall Telephone beans around the mulberry trunk to use and protect it with vines. We watered it all in with well water, and can’t wait to see what pops up! We have so many new varieties from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds and other sources that we’re planting this year! Today we move onto the next bed.