Plant Guild #8: Insectiaries

Insectiaries are plants which attract lost of pollinators to the rest of your plant guild. We’re not just talking honey bees. Actually, what Americans raise and call honey bees, any bees from the genus Apis which are colonial honey-producers, are all European. Of course there are also the African honey bees which are loose in America, but their ‘hotness’ – their radical and violent protective measures – are not welcome. There are no native honey bees in North America.

What we do have are hundreds of species of bees, wasps and flies which are native and which do most of the pollenization in non-poisoned gardens and fields. Here in Southern California where everything is smaller due to the low rainfall we have wasps, flies and bees which range in size from the inch-long carpenter bees to those the size of a freckle. A small freckle. In fact the best native pollinator we have is a type of hover fly that is about the size of a grain of rice.

My daughter Miranda hosts our Finch Frolic Garden Facebook page where she has posted albums of animals and insects found here, with identifications along with the photos so that you can tell what is the creature’s role in the garden (you don’t need to be a member of Facebook to view it).

We notice and measure the loss of the honeybee, but no one pays attention to the hundreds of other ‘good guys’ that are native and do far more work than our imports. Many of our native plants have clusters of small flowers and that is to provide appropriate feeding sites for these tiny pollinators. Tiny bees need a small landing pad, a small drop of nectar that they can’t drown in, and a whole cluster of flowers close together because they can’t fly for miles between food sources.

If you’ve read my other Plant Guild posts, you’ve already familiar with this, but here it goes again. You’ve heard of the ‘Three Sisters’ method of planting by the Native Americans: corn, beans and squash. In Rocky Mountain settlements of Anasazi, a fourth sister is part of that very productive guild, the Rocky Mountain bee plant (Cleome serrulata). Its purpose was as an insectiary.

So planting native plants that attract the insects native to your area is just as important as planting to attract and feed honey bees. Many herbs, especially within the mint and sage families, produce flowers that are enjoyed by most sizes of insects and are useful as food or medicine as well.

If you like flowers, here’s where you can possibly plant some of your favorites in your guild and not feel guilty about it! Of course, aesthetics is important and if you aren’t enjoying what is in your garden, you aren’t doing it right, so plant what makes you happy. As long as its legal.

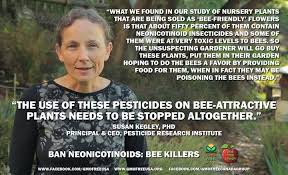

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.

Of course be sure to grow only non-GMO plants, and be ESPECIALLY sure that if you are purchasing plants they are organically raised! Although large distributors such as Home Depot are gradually phasing into organics, an enormous amount of plants sold in nurseries have been treated with systemic insecticides, or combination fertilizer/insecticides.  Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.

Systemic poisons work so that any insect biting the plant will be poisoned. It affects the pollen and nectar as well, and systemics do not have a measurable life span. They don’t disappear after a month or so, they are there usually for the life of the plant. If your milkweed plants don’t have oleander aphids on them, be wary! If the plants sold as food for pollinators and as host plants don’t have some insect damage to them, beware! They WILL sell you ‘butterfly and bird’ plants, but also WILL pre-treat them will systemic insecticides which will kill the Monarchs and other insects that feed on the plant, and sicken the nectar-sipping birds.  Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

Even those plants marked ‘organic’ share table space in retail nurseries with plants that are sprayed with Malathion to kill white fly, and be sure that the poison drift is all over those organic vegetables, herbs and flowers. Most plant retailers, no matter how nice they are, buy plants from distributors which in turn buy from a variety of nurseries depending upon availability of plants, and the retail nurseries cannot guarantee that a plant is organically grown unless it comes in labeled as such. Even then there is the poison overspray problem. The only way to have untainted plants is to buy non-GMO, organically and sustainably grown and harvested seeds and raise them yourself, buy from local nurseries which have supervised the plants they sell and can vouch for their products, and put pressure on your local plant retailers to only buy organic plants.

When public demand is high enough, they will change their buying habits, and that will force change all the way down the line to the farmers. No matter how friendly and beautiful a nursery is and how great their plants look, insist that they prove they have insecticide-free plants from organic growers (even if they don’t spray plants themselves). Systemic insecticides are bee killers. And wasp and fly killers as well.

Of course many of the other guild members will also attract pollinators, and even be host plants for them as well. With a variety of insectiaries, you’ll receive the benefit of attracting many species of pollinator, having a bloom time that is spread throughout the year, and if a plant is chewed up by the insect it hosts (milkweed by Monarch caterpillars, for instance) there will be other blooms from which to choose.

Placing fragrant plants next to your pathways also gives you aromatherapy as you pass by.

And flowers are pretty. So plant them!

You can find the entire 9-part Plant Guild series here: Plant Guilds: What are they and how do they work? The first in a series. , Plant Guild #2: Canopy , Plant Guild #3: Sub-Canopy , Plant Guild #4: Nitrogen-Fixers, Plant Guild #5: Mining Plants, Plant Guild #6: Groundcovers, Plant Guild #7: Vines, Plant Guild #9: The Whole Picture.

2 Comments

Diane

Thanks Don. Great photos!

Don Rideout

I just discovered your site and noticed that you mentioned Cleome (now Peritoma) serrulata. It’s a beautiful plant that I had never seen until recently. I was just in northern Arizona where I saw a field of it in someone’s back yard. If you would like to see my photos, here is a link to them on iNaturalist: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/7582562.